How Can They Love Us When They Hate Us?

The Dominican Republic 1969

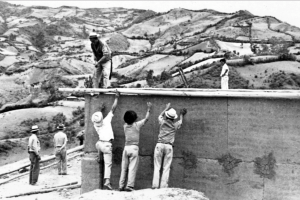

A group of men construct a home. Photo by Leland Cott.

My primary motivation for joining the Peace Corps in 1966 was one of answering my country’s call to service; and specifically one that was a substitute for the military. The Vietnam draft was a fact of life, and I had already received five years of educational deferments from the Selective Service for my architectural training. As was the case for so many young men at the time, I looked toward the post-graduate alternative experience offered by the Peace Corps.

As best I can recall, I did have a sense that the Peace Corps might prove to be an important rite of passage even beyond the words in the Peace Corps recruiting material. What I didn’t understand at the time was how great a formative experience my two years as a Peace Corps volunteer would turn out to be; one that continues to inform much of my life to this day.

My three months of Peace Corps training lived up to its legendary reputation for difficulty. About 40 of us, all roughly the same age, were exposed to tough physical and mental testing along with six hours of daily Spanish language training. My experience in the Peace Corps, from June 1966 until July 1968 was a complete change from anything I had previously known, from the very first moment I arrived at our two month training camp in Southern California. While training for one month in Mexico, in a village near Morelia, I lived in the same smell and filth from the farm animals as did my host family and always in utter poverty, in completely unsanitary conditions and without proper diet. In retrospect, I still marvel at how easy going and flexible we were then to allow that kind of radical change to wash over us so completely.

However, the prospect of living high in the Andes designing and building schools in mountain villages made the temporary “inconvenience” of the training experience seem worthwhile. 1966 was a different time, for sure; one during which our idealism formed many of our life decisions. We were, after all, going to change the world and make a difference.

That sense of idealism, coupled with my enthusiasm for architecture, was the perfect compliment with President Kennedy’s vision of the Peace Corps. The Peace Corps would become the natural next step in my personal and professional development. Earlier, during my three months of Spanish language and Acción Communal training in California and Mexico—where we learned how, as professional architects, we could support other Peace Corps volunteers working to provide for the needs of the rural Colombian peasants—I volunteered to be sent to a rural location in Colombia on the assumption that my efforts would be most appreciated by my host country nationals. Accordingly I was assigned to the distant, underdeveloped southern state of Nariño to live in Pasto, its capital city, a rather non-descript small city of 80,000 whose main feature was its location on the side of thought-to-be-extinct, but active, volcano Galeras.

My basic modus operandi for supporting the 20 local Peace Corps Acción Communal volunteers in Narino, was to design and assist with the construction of rural schools. Together, we developed a prototypical design made up of a single classroom and a small living space for the teacher, including a small kitchen and laundry (see illustration). When a local Peace Corps volunteer had organized a community to build a school, I would travel to that village to help with a small celebratory fund-raising fiesta. Beer sales revenue at these parties enabled us to purchase a corrugated asbestos cement roof, complete with skylights, for each school. Such a roof, mass- produced by the Eternit Company, was considered to be an improvement over the traditional heavy opaque clay tile roofing. I would then set to work with a few men in the volunteer construction crew to lay down the outline of the walls and foundation, using a Peace Corps issued transit and tripod, so that we could hand-excavate an accurate rectangular foundation.

It would usually take a month or so to build the heavy rammed earth walls and eucalyptus-wood roof trusses that would bear the weight of the corrugated cement roof panels. During that month-long process, I would return from time to time to check that everything was being built to my specifications and then finally at the end for a final check on the placement of the roof panels. The beer bottle caps, saved from our party the previous month, were nailed to the exterior walls about twelve inches apart to act as a screed to hold the plaster on the wall’s vertical surface. The plaster was usually mixed, on-site, with hair that we would cut from the manes of the village horses to act as a binder (horsehair plaster was the way it was done in the United States as well). The local joke was that you could always tell where I had built a school because the horses had no hair! A badge of honor, of sorts!

Pages more could be written about many aspects of my experience during those 24 months in Colombia building schools, access roads, bridges, market places and parks. Aside from the obvious adventure of it all, it ultimately was a time that profoundly influenced my attitudes about Latin America. During my time here in Cambridge, on the Faculty of the Graduate School of Design, I have consulted with the Mexican Government on housing policy and run four semesters of urban design and planning studios in Havana, Cuba. Two years ago, working as a private consultant along with the National Trust for Historic Preservation and the Cuban Government, I assisted with the restoration and preservation of Ernest Hemingway’s Havana home, the Finca Vigia. It brought back memories of building elsewhere in Latin America, including our use of Eternit corrugated asbestos cement roof panels, (purchased in Colombia!) to cover Papa Hemingway’s writing studio.

It’s now been 40 years since my return from Pasto, Colombia. The recent violence associated with the Colombian drug wars has had a serious negative effect on that city as well did the devastating volcanic eruption of Mt. Galeras in 1993. I may never return to that city, of which I have so many fond memories. But Pasto and its people taught me invaluable lessons and the experience laid the groundwork for wanting to serve as a citizen of the world, to make a difference.

Winter 2009, Volume VIII, Number 2

Leland Cott is an Adjunct Professor of Urban Design at the Harvard Graduate School of Design where he teaches design studios and seminars about the design of housing; and is also the coordinator for the Master of Design Studies (MDesS) Housing and Urbanization specialization. At DRCLAS, he is a member of the Cuba Committee and Faculty Advisory Committee. He is a Founding Principal of Bruner/Cott & Associates, a 60-person architecture and planning firm in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter: The Sixties

When I first started working on this ReVista issue on Colombia, I thought of dedicating it to the memory of someone who had died. Murdered newspaper editor Guillermo Cano had been my entrée into Colombia when I won an Inter American Press Association fellowship in 1977. Others—journalist Penny Lernoux and photographer Richard Cross—had also committed much of their lives to Colombia, although their untimely deaths were …

The True Impact of the Peace Corps: Returning from the Dominican Republic ’03-’05

I am an RPCV: a Returned Peace Corps Volunteer. For me the Peace Corps was an intense life experience, above anything else. As I continue to reflect on it, I am struck with the many and varied ways in which it continues to affect my life. As a PCV in the Dominican Republic from September 2003 to November 2005, I lived, worked, and learned in a small sugar cane-dependent community two hours outside of Santo Domingo…

In the Shadow of JFK: One Peace Corps Experience

I am often asked about the Peace Corps by students and recent graduates. The most frequent questions are, “why join?”, “what did you do?”, and “what has it meant for your career?” Here is my story. My earliest recollection of international curiosity was in the fourth grade when Sister Margaret Thomas described her experience as a recently returned missionary in Bangladesh. In high school, my sister Mary went to Peru on …