El Faro

Online Media and a Response to Violence

El Faro got its start as an online medium in San Salvador in 1998. El Salvador had just emerged from 12 years of a cruel civil war. The 1992 peace agreements, signed between a rightist government (and its army) and a leftist guerrilla force (the FMLN), marked a new beginning for the country, with guaranteed political participation for all parties in the political spectrum and a new set of institutions to start a new democratic process.

In this context, the media found themselves in a totally new situation. An entire generation of journalists—used to working in the rightist confines of a restricted press—was soon replaced by young, inexperienced reporters right out of college.

As such, two sons of exiles, Jorge Simán and I, returned to El Salvador to start a new medium that would be honest and fresh, treating its public like intelligent people.

Because of our lack of resources to start a print medium—rather than a visionary perspective—El Faro began as an Internet operation. We had no money to pay reporters. Also, since the Internet at the time was almost nonexistent in a poor country like El Salvador, it took us a while to earn a place among Salvadoran media.

Now, El Faro is well-known both in El Salvador and internationally. And El Salvador faces a different and escalating situation, a security crisis spearheaded by organized crime.

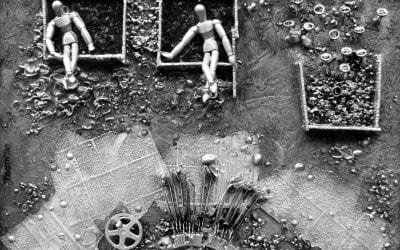

Thus, in January of this year, El Faro inaugurated Sala Negra, a section dedicated exclusively to the coverage of violence and organized crime, but in long formats. We intend to publish in-depth stories and investigative pieces, as well as that most Latin American of genres: the chronicle. We will also produce photoreportages and documentary films.

This initiative comes after months of reflection. We—El Faro co-founder Jorge Simán and I—became convinced that journalism’s only morally valid answer to the security crisis in El Salvador is precisely through long formats, which require the application of both journalistic and academic methods to understand what is happening. Only that contextual understanding can explain the crisis to our readers.

Ever since its inception in April 1998, before Google was born, El Faro has been growing constantly, experimenting with new forms and searching for different ways to tell compelling and relevant stories. The Sala Negra is just one component of El Faro, but one that tries to find different ways to explain the crisis of violence that goes beyond the usual way of reporting on daily body counts.

Several articles in this issue of ReVista focus on the situation of violence in Mexico. However, Central America is now confronting one of its most difficult moments since the armed conflicts that made headlines worldwide in the ’80s. This time, a different kind of violence threatens the stability of the region: organized crime in the form of gangs and drug cartels.

For the first time since the end of the armed conflicts, the world begins to see Central America once again as a crucial part of the criminal and political turmoil of Latin America.

Today, the northern triangle of Central America (El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras) is the most violent part of the world, with homicide rates up to 70 per 100,000. This only worsens a politically unstable situation, with Daniel Ortega’s authoritarian government in Nicaragua; the aftermath of a coup d’état in Honduras and the long-scale infiltration of the Guatemalan state structures by organized crime.

While El Salvador is politically more stable than its neighbors, the country is experiencing a deep economic and social crisis. There is mounting evidence of the participation of law enforcement officers in organized crime. In addition to the seemingly unstoppable problems of gangs, crude violence, drugs and arms-smuggling activities, extorsion and vendetta killings facilitated by an extremely high impunity rate, the country now directly faces the incursion of Mexican drug cartels already present in neighboring Guatemala and Honduras.

The First Years

Our new section is very much in keeping with our history and our ideals. When we first started, journalism students, full of dreams and passion, came to us and built a newsroom where open debate and self-criticism became—and still are—the best ways to grow and learn from each other. This attitude enabled us to build a strong brand identity—one that is now reflected in the Sala Negra.

We knew from the beginning that we didn’t want to compete with mainstream media. At a time when Internet gurus all over the world advised that we should go for short and late-breaking news, we insisted on long pieces published weekly. Again, we acted on what we wanted to do, rather than on some strategic vision of the future of online media.

Somehow our stubbornness paid off. Our readers found in our exclusive coverage, our in-depth stories and our narrative efforts an identity they liked, and they began to follow the website regularly. El Faro started to earn respect, prestige, and many more readers. We can attribute this success to publishing articles that others preferred to ignore, revealing facts the government tried to keep hidden and running stories about powerful people nobody else dared to touch.

For the first seven years, everybody involved in the production of El Faro worked on a voluntary basis. We were not successful selling ads and we didn’t have a proper business plan. Internet penetration in El Salvador was by then around 10 percent; the advertising market had no faith in the Internet and no will to place an ad in a medium that was critical of the establishment.

But during those seven years we also had the chance to train a whole generation of Salvadoran journalists (and watch how, after a while, they left for mainstream newsrooms to continue their professional careers while finally earning a salary).

In 2003, a pre-electoral year, we launched a special project to cover the presidential elections. We published our mandate: we are not covering campaigns but the electoral process. Thus, we caught the attention of a couple of international agencies; for the first time, we had money to hire three reporters and a photographer for more than a year. They became the first people who ever received a penny from El Faro.

Since then, we have designed several multimedia projects and stimulated debates on issues of politics, immigration and violence with support from other organizations. We have increased both our sales and other sources of revenue. This has allowed us expand out newsroom to more than 25 employees, producing materials across different platforms such as photography, radio, video, text, multimedia, books, DVDs, and conferences. Our newsroom is for the most part made up of people who had their first journalistic experience at El Faro many years ago. They have come back with much more experience, hunger and passion. And they are now training a new generation of journalists.

Democracy at Stake

It is often said that there is no democracy without independent media; but the opposite is also true: there are no independent media without a democracy. Today, the democratic processes of the Central American countries are at risk. The levels of violence, impunity and victimization are alarmingly high, and citizens demonstrate, in poll after poll, less hope and more inclination to support other types of regimes if they can guarantee safety and a decent living. Democracy, they say, has not been able to satisfy those basic needs.

The problem, of course, is that democratic institutions have not been able to deliver a better life for citizens. Even though we have registered great achievements since the end of the armed conflicts, the status of institutions in Central America has regressed in most cases and stalled in El Salvador, the healthiest country in that context.

We strongly believe that independent media play a crucial role in demanding accountability and pointing out what is not being done right in the state institutions. Thus, we put a strong emphasis on investigating corruption and abuse of power.

But we also believe that independent media should help strengthen a middle class and its values, opening spaces for public discussion and debate. In searching for knowledge and understanding, the media provide intellectual tools for citizens to better understand reality and make decisions.

For such media to thrive, it is not enough to have these convictions and good journalists and editors to put them into practice. A good public is also necessary. We have a very demanding readership that has pushed us to constantly improve our work; a passionate readership that shows a much higher loyalty and sense of belonging than that of the mainstream media, constantly providing us with feedback through every possible way.

As we face new challenges, we will continue putting our imagination at the service of our journalism; that is, experimenting with new narratives and creating new projects that we think may help toward the construction of a better society with happier human beings.

Nowadays that vision requires even stronger dedication. Hard times lie ahead. But it is precisely in such moments that our choices, and the work we do, can be more important.

Spring 2013, Volume XII, Number 3

Carlos Dada is the founder and director of El Faro. He received the 2010 Latin American Studies Association Media Award for the excellence and social relevance of the online publication.

Related Articles

New Journalists for a New World

I received a surprising phone call one day in late 1993, when I was the director of Telecaribe, a public television channel in Barranquilla, Colombia. The caller was none other than Gabriel García Márquez. “Will you invite me to dinner?” he asked me. “Of course, Gabito,” I…

Latin American Nieman Fellows

A few days after I arrived at Harvard in August 2000 to begin my work as curator of the Nieman Foundation for Journalism, Tim Golden, an investigative reporter for the New York Times in Latin America, phoned me. “Could I find a place in the new Nieman class for a Colombian…

Freedom of Expression in Latin America

In June 1997, Chile’s Supreme Court upheld a ban on the film “The Last Temptation of Christ,” based on a Pinochet-era provision of the country’s constitution. Four years later, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights heard a challenge to this ban and issued a very different…