Mexican Machos and Hombres

“Are any of you married?” I asked the muchachos.

“No, todos solteritos, all young and single,” said Felipe.

“That bozo’s got two little squirts. He’s the macho mexicano,” said Rodrigo, pointing to Celso, the father of two children who lived with their mother in another city.

“What does that mean?” I inquired.

“Macho? That you’ve got kids all over,” said Esteban.

“That your ideology is very closed,” said Pancho. “The ideology of the macho mexicano is very closed. He doesn’t think about what might happen later, but mainly focuses on the present, on satisfaction, on pleasure, on desire. But now that’s disappearing a little.”

“You’re not machos?” I asked.

“No, somos hombres, we’re men.”

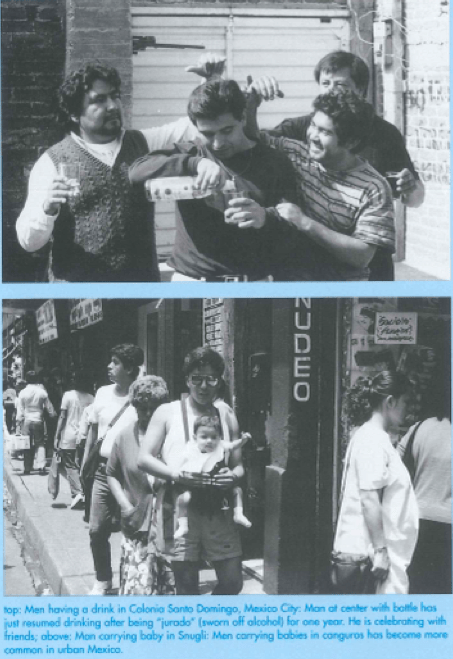

These young men were my neighbors during the time of my ethnographic fieldwork on changing male identities in Santo Domingo. What it means to be men and women has changed drastically for people of all ages in this working class, squatter neighborhood on the south side of Mexico City, as it has in other poor areas of the Mexican capital. Such change influences parenting, participation in political movements, paid work, education, sexuality, and more. Women have played a prominent role in this colonia, founded by land invasion, so residents have also been challenging gender relations inherited from the past. Women were often called upon to physically defend their community from invasion-busters. In the process, they became leaders and key decision-makers. Gender politics in Mexico is simply not that simple, as my experience in this neighborhood taught me.

Journalists and academics often seem intent on discovering a ubiquitous, virulent, and “typically Mexican” machismo. Such stereotyping stems in part from earlier national character studies in anthropology, as well as U.S. media and social scientific writings, that generalize about Mexican cultural history, including the role played by gender.

Gender politics are emerging and diverging in today’s Mexico. Women and men in Colonia Santo Domingo say macho men are not as prevalent as before. Some older men like to divide the world of males into machos and mandilones (female-dominated men), where the term macho connotes a man responsible towards his family. For older men, to be macho more often means to be un hombre de honor, an honorable man.

However, younger married men in Colonia Santo Domingo tend to define themselves in a third category, the “non-macho” group. “Ni macho, ni mandilón, neither macho nor mandilón,” is how many men describe themselves. Others may define a friend as “your typical macho mexicano,” while the friend rejects the label, describing his helpfulness to his wife or pointing out that he doesn’t beat her (one of the few generally agreed upon attributes of machos). The men don’t necessarily agree about what macho, machismo, and machista mean, but most consider them to be pejorative concepts, not worthy of emulation.

These men are precisely betwixt and between marked cultural positions a clear illustration that, like other cultural identities, notions of masculinity and femininity must be understood in historic relation to other divergent cultural trajectories such as class, ethnicity, and generation.

Anthropologists and the Creation of Mexican Machismo

Because of his crispness, scope, and vigor in presentation, Oscar Lewis is a central anthropological ancestor for the study of Mexican machismo. His descriptions in The Children of Sánchez (1961) and other books form a point of reference for contemporary students. Also, his theoretical formulations are still delightfully provoking, if too often insufficiently developed, as with regard to the concept of machismo.

However, some scholars have utilized details from Oscar Lewis’s ethnographic studies to promote sensationalistic generalities far beyond anything Lewis himself wrote. For instance, in David Gilmore’s (1990) widely read survey of the Ubiquitous (if not Universal) Male in the World, machismo is discussed as an extreme form of manly images and codes. Gilmore sees modern urban Mexican men mainly as exaggerated archetypes, constituting, with other Latin men, the negative pole on the continuum of machismo to androgyny of male cultural identities around the world. To make his ethnographic points about Mexican men, Gilmore cites Lewis:

In urban Latin America, for example, as described by Oscar Lewis (1961: 38), a man must prove his manhood every day by standing up to challenges and insults, even though he goes to his death “smiling.” As well as being tough and brave, ready to defend his family’s honor at the drop of a hat, the urban Mexican… must also perform adequately in sex and father many children. (1990: 16)

But even if Lewis’ ethnographic descriptions, compiled in the 1950s, were just as valid decades later, he did not usually generalize in this fashion about the lives of Jesús Sánchez and his children. His anthropology was often artfully composed, and although some of his theories were naive, he generally tried to keep “mere” romance and fancy out of his ethnographic descriptions.

Cowboys and Racism

Many anthropologists and psychologists writing about machismo utilize characterizations like manly, unmanly, and manliness without defining them. They seem to assume, incorrectly in my estimation, that all of their readers share a common definition and understanding of such qualities.

In a brilliant essay published in English in 1971, Américo Paredes provides several clues as to the word history of machismo, and in the process draws clear connections between the advent of machismo and nationalism, racism, and international relations. Paredes explores folklore a good indicator of popular speech and determines that in Mexico, prior to the 1930s and 1940s, the terms macho and machismo do not appear. The word macho existed, but almost as an obscenity, similar to later connotations of machismo. Other words were far more common at the time of the Mexican Revolution: hombrismo, hombría, muy hombre, hombre de verdad (all relating to hombre, man), and valentía, muy valiente, etc. (relating to valor, courage). Despite the fact that during the Mexican Revolution the phrase muy hombre was used to describe courageous women as well as men, the special association of such a quality with men then and now indicates certain points in common, regardless of whether the words macho and machismo were employed.

Making a connection between courage and men during times of war in which men are the main, though assuredly not the only, combatants is nevertheless not the same thing as noting the full-blown “machismo syndrome,” as it is sometimes called. Courage was valued during the Revolution for both men and women, though the terms used to refer to courage carried a heavy male accent. Beginning in the 1940s, the male accent itself came to prominence as a national(ist) symbol. For better or worse, Mexico came to mean machismo and machismo, Mexico, providing an illustration of what Mary Louise Pratt shows to be the “androcentrism of the modern national imaginings” in Latin America.

The consolidation of the nation-state and party machinery throughout the Mexican Republic and the development of the country’s modern national cultural identity took place on a grand scale during the presidencies of Lázaro Cárdenas and Manuel Avila Camacho (1934-1946). After the turbulent years of the Revolution and the 1920s, and following six years of national unification under the populist presidency of Lázaro Cárdenas, the national election campaign of 1940 opened an era of unparalleled industrial growth and demagogic rule in Mexico. Coincidentally, one of the campaign slogans of the ultimately successful presidential candidate Avila Camacho was: “Ca … MACHO!” As Paredes points out, the president was not responsible for the use of the term macho, but, as he writes, “We must remember that names lend reality to things.”

The word history of machismo is but a piece of the puzzle of the outlooks and practices codified in tautological fashion as instances of machismo. For Paredes, the peculiar history of U.S.-Mexican relations has produced a marked antipathy on the part of Mexicans for their northern neighbors. The image of the frontier and the (Wild) West has in turn played a special role in this tempestuous relationship, with the annexation of two-fifths of the Mexican nation to the United States in 1848, and repeated U.S. economic and military incursions into Mexico since then, undercutting proclamations of respect for national sovereignty.

Paredes reminds us that trade between the two countries initially included the export of the Mexican vaquero-cowboy to the United States. In the early 19th century, frontiersmen were forging the way for the expanding Jacksonian empire. Their combination of individualism and sacrifice for the higher national good came to embody the machismo ethos. Contemporary popular usage of the term machismo in the United States often serves to rank men according to their supposedly inherent national and racial characteristics, as in, “My boyfriend may not be perfect, but at least he’s no Mexican macho.” Such statements use non-sexist pretensions to make denigrating generalizations about fictitious Mexican male cultural traits.

Jorge Negrete and Lo Mexicano

The ideological and material consolidation of the Mexican nation was fostered early on, not only in the gun battles on the wild frontier and in the voting rituals of presidential politics, but also in the imagining and inventing of lo mexicano, mexicanidad in the national cinema. And of all the movie stars of this era, the singing cowboy Jorge Negrete, handsome and pistol-packing charro, stood out as “a macho among machos.” He came to epitomize the swaggering Mexican nation, singing in Yo Soy Mexicano:

I am a Mexican, and this wild land is mine.

On the word of a macho, there’s no land lovelier

and wilder of its kind.

I am a Mexican, and of this I am proud.

I was born scorning life and death,

And while I have bragged, I have never been cowed.

The macho mood was forged in the rural cantinas, the manly temples of the Golden Age of Mexican Cinema. Mexico appeared on screen as a single entity, however internally incongruent, while within the nation the figures of Mexican Man and Mexican Woman loomed large.

The distinctions between being a macho and being a man were starting to come into clearer focus in the Mexican cinema of the 1940s. In the late 1940s, Octavio Paz dissected Mexican machismo, and his work has come to represent the official view of essential Mexican attributes: like machismo, loneliness, and mother worship. When Paz writes in The Labyrinth of Solitude, “The Mexican is always remote, from the world and from other people. And also from himself,” he should not be taken literally but literarily. Part of the reason for the elegance of this book may be that Paz was creating as much as he was reflecting on qualities of mexicanidad. As he put it in his Return to the Labyrinth of Solitude, “The book is part of the attempt of literally marginal countries to regain consciousness: to become subjects again”

Paz writes with regard to men and women in Mexico, “In a world made in man’s image, woman is only a reflection of masculine will and desire.” In Mexico, “woman is always vulnerable. Her social situation as a repository of honor, in the Spanish sense and the misfortune of her ‘open’ anatomy expose her to all kinds of dangers.” Biology as destiny? But there is nothing inherently passive, or private, about vaginas in Mexico or anywhere else. Continuing with Paz, just as “the essential attribute of the macho” or what the macho seeks to display, anyway is power, so too it is with “the Mexican people.” Thus, mexicanidad, Paz tell us, is concentrated in the macho forms of “caciques, feudal lords, hacienda owners, politicians, generals, captains of industry.”

Many Mexican men are curious about what it means to be a Mexican, and what it means to be a man. One is not born knowing these things; nor are these things truly discovered. They are learned and relearned.

In Colonia Santo Domingo, in addition to Paz, people use Oscar Lewis in the stories they tell about themselves. Or at least what people have heard about his anthropological writings (Lewis is “remembered” far more than he is read). We anthropologists may well ask where the need to see pervasive machismo comes from, and why so many have used Lewis to prove their own preconceptions and prejudices.

In the dramas which people in colonias populares offer about their own and others’ marriages, the roles of self-designated machos are not all playful by any means. “We cheat on our wives because we’re men,” said one acquaintance. “We want to be macho.” What does this mean, “we want to be macho,” except that “to be macho” is an ideological stance which can only be sanctified by others?both men and women?and by oneself? In my discussion with the muchachos, while one of them said that they were not machos but rather hombres, men, Celso insisted that, as men, they were by definition machos. He said that if they needed to call themselves something, mandilón and marica (queer) were obviously inappropriate. So what else did this leave except macho?

The description provided by Celso makes it appear that the youths rummage around in an identity grab-bag, pulling out whatever they happen upon, as long as it is culturally distinct. One minute these muchachos identify themselves as machos, who enjoy bragging about controlling women and morally and physically weaker men. The next minute the same young men express bitterness at being the ones on the bottom.

Redefinitions

Delineating cultural identities and defining cultural categories one’s own and those of others is not simply the pastime of ethnographers. While no one in Santo Domingo might explicitly divide the population of men this way, I think most would recognize the following four male gender groups: the macho, the mandilón, the neither-macho-nor-mandilón, and the broad category of men who have sex with other men. But the fact that few men or women do or would care to divide the male population in this manner reveals more than simply a lack of familiarity with the methods of Weberian ideal typologizing. Masculinity, like other cultural identities, is not confined so neatly in categories like macho or mandilón. Identities only make sense in relation to other identities, and they are never firmly established for individuals or groups. Further, consensus as to whether a particular man deserves a label such as neither-macho-nor-mandilón is rarely found. He will likely think of himself as a man in a variety of ways, none of which necessarily coincides with the views of his family and friends.

No man in Santo Domingo today fits neatly into one of the four categories, at specific moments, much less throughout the course of his life. Further, definitions such as these resist other relevant but complicating factors like class, ethnicity, and historical epoch. Machismo in Colonia Santo Domingo has been challenged ideologically, especially by grassroots feminism and more indirectly by the mainly middle class feminist and gay rights movements. But it has also faced real if usually ambiguous challenges in the form of strains of migration, falling birthrates, exposure to alternative cultures on TV, and so on. These economic and sociocultural changes have not automatically led to corresponding shifts in male domination, in the home, the work place, or society at large. But many men’s authority has been undermined in material, if limited, ways, and this changing position for men as husbands and fathers, breadwinners, and masters has in turn had real consequences for machismo in Santo Domingo.

In Colonia Santo Domingo, as elsewhere in the Republic, the fate of machismo as an archetype of masculinity has always been closely tied to Mexican cultural nationalism. My good friend César commented to me one day about drinking in his youth, “More than anything we consumed tequila. We liked it, maybe because we felt more like Mexicans, more like lugareños [equivalent to homeboys].”

For better or for worse, Ramos and Paz gave tequila-swilling machismo pride a place in the panoply of national character traits. Through their efforts and those of journalists and social scientists on both sides of the Rio Bravo/Grande, the macho became “the Mexican.” This is ironic, for it represents the product of a cultural nationalist invention. You note something (machismo) as existing, and in the process help to foster its very existence. Mexican machismo as national artifact was, in this sense, partially declared into being.

In all versions, Mexican masculinity has been at the heart of defining both the past and future of a Mexican nation. Like religiousness, individualism, modernity, and other convenient concepts, machismo is used and understood in many ways. We either accept the multiple and shifting meanings of macho and machismo or we essentialize what were already reified generalizations about Mexican men. Like any identity, male identities in Mexico City do not reveal anything intrinsic about the men there. Their sense and experience of being hombres and machos is but a part of the reigning chaos of the lives of men in Colonia Santo Domingo, at least as much as the imagined national coherence imposed from without.

Fall 2001, Volume I, Number 1

Matthew C. Gutmann is the Stanley J. Bernstein Assistant Professor of the Social Sciences-International Affairs in the Department of Anthropology at Brown University.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter: Mexico in Transition

You are holding in your hands the first issue of ReVista, formerly known as DRCLAS NEWS.

Over the last couple of years, DRCLAS NEWS has examined different Latin American themes in depth.

The View from Los Angeles

In 1999, on returning home to LA after four years at Harvard and in the Boston area,I ascended to the city of Angels for the annual gala dinner of the premier civil rights firm: the Mexican American…

What’s New about the “New” Mexico

On July 2, 2000, Mexican voters brought to an end seven decades of one-party authoritarian rule. Just over a year later, Mexico continues to feel the repercussions of this momentous victory…