What Two Can Do

Bilingual Benefits through Pre-Texts

The majority of the world’s population speaks more than one language. That means, normally, that people communicate through two or more codes to construct complex world views. To think in different grammatical systems is an advantage when it comes to negotiating among people with a variety of world views.

My parents, who immigrated from Eastern Europe to New York City, for example, spoke quite a few languages. This may be astounding for most Americans, north and south. In fact, people would correct them, as if they had wanted to say that English was their “second language” rather than the seventh. But for East Europeans, or West Africans, multilingualism is the norm. Though the concept of a universal “deep grammar,” made popular by linguist Noam Chomsky, argues for the basic coherence of language systems (and by extension the universality of the human condition), difference matters culturally and politically. It is one thing to say “I like you,” and another to say “Me gustas” [You please me.] The English version puts me in the center of the sentence. In Spanish, I humbly occupy the position of object who responds to you, the subject.

Accents matter too. Some enjoy higher status than others, and part of bilingual education should be to cultivate a taste for the range of accents. An underdeveloped taste for difference can have murderous consequences. Think, for example, of the racist massacre ordered by Trujillo in 1937. Racism against Haitians at the Dominican border wasn’t a matter of color but of pronunciation. This is often the case. “Say ‘perejil’” was the order that identified who would live and who would die because Haitians pronounced the word one way, and Dominicans another. This was a linguistic border between life and death; the geographical border is a river now known as El masacre.

Bilingual education is, therefore, a political pedagogy, as much for the speakers of several languages as for the monolinguals who come into contact with difference and who can learn to love it through acquired agility and capaciousness. Language classes are therefore more than technical training to communicate what we already know. They are crucial for troubling our confidence in any one code. The difficulties that learners will encounter find compensation in new pleasures from foreign sounds and strangely apt grammatical constructions. These personal and public skills are available from any combination of languages, so that undervalued languages become as pedagogically precious for native speakers as the hegemonic languages they are bound to learn.

In 2009, while bilingual education was still illegal in Massachusetts (banned since 2002 and recently reinstated), Boston’s Assistant Superintendent for English Language Learners, Eileen de los Reyes, responded to demands for Spanish language instruction from mostly Colombian and Salvadoran parents.

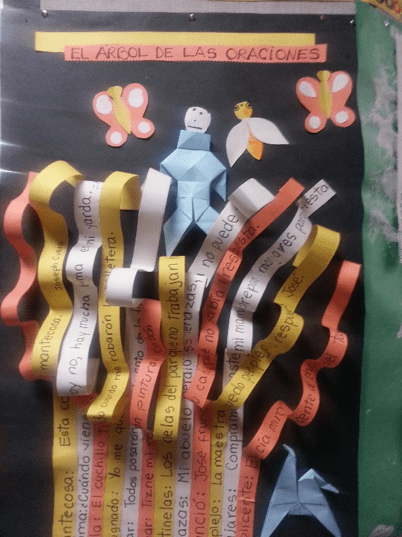

De los Reyes, who had taught at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, engaged the Cultural Agents Initiative at Harvard University to train bilingual teachers in Pre-Texts for a summer enrichment program. Then the program extended into an equally voluntary series of Saturday sessions during the school year. Pre-Textsis a user-friendly and intuitive protocol, based on Latin American traditions, that achieves both academic and social development. Adding prompts that work like acupuncture (an apparently focused move activates the whole person) to universal participation amounts to effective pedagogy. With Pre-Texts students hear a complex text read aloud (as was done in tobacco factories in the Spanish Caribbean including New York City) and then ask the text questions (about vocabulary, concepts, intention, anything). These opening moves pull out threads from the text (textile has the same root) and prepare students to propose art activities to play with the material, and thereby to master it.

Having students propose the activities authorizes them to co-create a session, even if the text is assigned by the teacher. This makes 21st-century skills (creativity, critical thinking, communication and collaboration) follow from improvising lessons with a text that students might not have chosen. How else can learning be student centered? Without participatory construction of projects, teachers will continue to impose obligatory curricula and predictable approaches. The co-creation of new approaches to a text through students’ preferred art forms (dance, or rap, song, drawing, calligraphy, film, fashion, sculpture, photography, etc.) requires and therefore develops a range of skills and capacities.

With a simple prompt: “Use this text to make art,” facilitators achieve what amounts to educational acupuncture, pressing on academic material to fire the pleasures of creative autonomy. Those pleasures drive literacy, innovation, and citizenship like gears of a holistic system that drives civic values. The next prompt, “go off on tangents” to bring in material related to the required text, ignites intellectual curiosity along with appreciation for culturally diverse classmates who bring in unpredictable material that multiplies perspectives and deepens interpretation. Cognitive and emotional learning go together here. The invitation to play with complex texts fuels critical thinking, enjoyment of one’s own particularity and admiration for others.

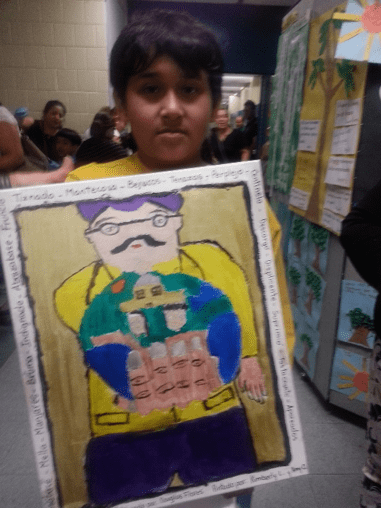

That first summer of our five-year collaboration with Boston Public Schools (BPS) we used a chapter from The Little Prince by Antoine Saint Exupéry as a pretext for art-making (painting, poetry, theater, dance, music, etc.]. The choice responded to the Assistant Superintendent’s question about what the third grade cousins of these East Boston children were reading in home countries. A BPS administrator worried aloud about setting the bar too high for a summer program, but Eileen de los Reyes insisted that her “little intellectuals” could rise to heights. She was right.

Pre-Texts had already begun to work in a Barr Foundation program called “Culture for Change” directed by Klare Shaw, then senior associate at the Barr Foundation and now Director of Programs at Liberty Mutual. One memorable workshop in the Irish-identified “Eastie” neighborhood played with “The Two Kings and the Two Labyrinths,” a short story by Jorge Luis Borges. How could we not have predicted that one teen led an activity would be to make models of a labyrinth? In retrospect, the session seems necessary and obvious. It responded to the leader’s question about what labyrinth meant.

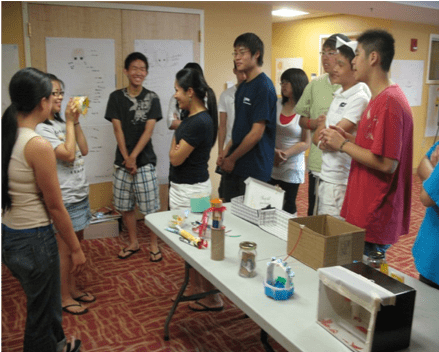

In Boston’s Chinatown Neighborhood Center artist-educators adapted Pre-Texts for collaborations between Chinese and Chinese American youth. The bilingual setting is, as always, a challenge and an opportunity. Through train-the-trainers workshops we used The Woman Warrior by Maxine Hong Kingston to interpret freely and to reinvent the narrative. One teaching artist speculated that the mother in the novel’s opening pages was lying to her daughter. He reasoned that the humiliated fallen woman who haunts those first pages is no relative of the family, despite what the narrator’s mother says, but an invented story meant to terrify the college-bound girl, lest she become promiscuous once she leaves home. This reading lesson was a revelation for the Cultural Agents facilitators who hadn’t imagined the dynamic, apparently familiar to Chinese families. The Boston Chinatown Neighborhood Center project culminated in an art installation at the Oak Street Fair in Chinatown. Youth produced visual art, poetry, photography, architecture and music, all inspired by challenging texts.

By now, Pre-Texts has seeded English language workshops in China (where the ripple effect has spread to Chinese language arts and to winning prizes for creative writing in Chinese), in Atlanta through Emory University collaborations, Dublin, but mostly in Latin America. In 2017 UNESCO designated Pre-Texts as the prize “Education for Peace” to be administered by the Ministry of Education. In Latin America, Portuguese and Spanish have been our target languages, although English instruction is on our agenda. So far, Ministries of Culture and Education, The Housing Authority in Buenos Aires, have engaged us in Portuguese and Spanish language learning. But for a local city government in a difficult neighborhood in Madrid, Spanish was a second language for most participants. They are in the vanguard of the country’s cultural policies, because required bilingual education is on the books in Spain. Hopefully the practice will catch up with the legislation toward an inclusive political vision.

East Boston children continue to represent our best case for improvement of the target language (English) by learning to love the home language (Spanish). Pre-Texts conjugates improvement with enjoyment. Much of the success owes to three graduate students from Harvard’s Department of Romance Languages and Literatures. Obed Lira, Jeronimo Duarte Riascos and Alberto Castillo Ventura made good on their humanistic training to stretch beyond the academic cloister. Based on their extensive readings and their developed literary taste, they composed an admirable Antología de clásicos latinoamericanos para lectores de segundo a quinto grado. (Pre-Textos, BPS, 2013) The table of contents might have been intimidating for children in second to fifth grades. But here, Borges, Darío, Martí, García Márquez, Mistral, and many others became beloved playthings for the animated participants.

ÍNDICE

- Cultivo una rosa blanca de José Martí

- Sonatina de Rubén Darío

- La rana que quería ser un rana auténtica de Augusto Monterroso

- La mosca que soñaba que era una águila de Augusto Monterroso

- Oda a la abeja de Pablo Neruda

- La abeja haragana de Horacio Quiroga

- Oda al gato de Pablo Neruda

- La exclamación de Octavio Paz

- Todo es ronda de Gabriela Mistral

- Las medias de los flamencos de Horacio Quiroga

- El ahogado más hermoso del mundo de Gabriel García Márquez

- Un señor muy viejo con unas alas enormes de Gabriel García Márquez

Libros que se pueden pedir:

Platero y yo de Juan Ramón Jiménez

El hombre que lo tenía todo, todo, todo de Miguel Ángel Asturias

El principito de Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

Las fábulas de Esopo edición de Edimat Libros—Clásicos de la literatura Series 2009

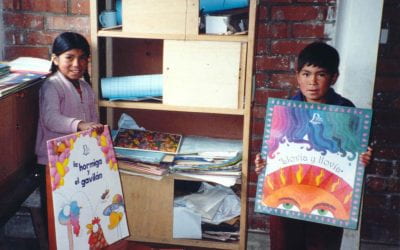

Obed (on the right) likes to tell an anecdote about a small for his age eight-year old boy called Arturito who asked if he could recite “Sonatina” (La princesa está triste), by Rubén Darío. After the child performed the entire poem, Obed surprised and delighted, asked Arturito why he had memorized it. “Because it’s so beautiful, maestro. Listen again.” That night Obed committed the poem to his own memory, with admiration for his student. On a series of Saturdays, the children played with this piece and other standards of Latin American literature; they painted, danced, role-played, etc.

But the mothers objected when they saw happy, sweaty, paint-stained children at pick-up time. Had they lobbied for Spanish instruction and mobilized their families on Saturday mornings to find their children distracted with arts and crafts? De los Reyes and I decided that the only way to assuage their concern was to engage the mothers in a session of Pre-Texts. This was a turning point for the families. Parents discovered how challenging it was to describe a character from a poem and have their children draw the description; they were stumped and then delighted when their children described characters, or metaphors, to be drawn. The effect was profound pleasure and admiration for the sons and daughters who handled classic texts with the fearless intensity of co-authors.

By the summer of 2013, when Superintendent Carol Johnson saw the display of artwork and the performances based on Miguel Angel Asturias’ children’s novel El hombre que lo tenía todo, todo, todo, Pre-Texts was poised to enrich public schooling beyond English Language Learner (ELL populations).

Johnson understood that the Pre-Texts protocol managed to merge academics and art—which was her stated mission as Superintendent– and that the approach would be welcome in African American as well as immigrant neighborhoods. She retired soon afterwards, and Pre-Texts has waited for another opportunity to partner with BPS. It has come through an educational research project, coordinated through Harvard sociologist William Julius Wilson. As a corollary to his major study of Boston’s patterns of deep poverty and racial inequalities, Pre-Texts represents an opportunity to measure the impact of an intervention to change conditions. Literacy, as most scholars of development agree, is basic to progress in any field (employment, public health, gender relationships, political engagement, etc).

Meanwhile, Pre-Texts continues to develop bilingual education through trainings at Harvard University, in Romance Languages and Literatures and the Bok Center for Teaching and Learning, to grade schools throughout Latin America, Dublin and China. It has been adopted by the Global Leaders Program for young musicians who meet during January in Frutillar, Chile, to develop pedagogical and entrepreneurial skills. During the recent session, we used a story by José María Arguedas, “La agonía de Rasu-Ñiti” which debuted for Pre-Texts in honor of Salvador del Solar, then Visiting Fellow at the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies and now Prime Minister of Peru. The Instituto de Vivienda Ciudad (IVC) in Buenos Aires rolled out an impressive Pre-Texts project for developing neighborhoods (no longer called villas miserias) where Andean immigrants struggle to make a home. And in Paraguay we are poised to work with the Ministry of Development to address corruption in the courts. Currently, we are preparing a collection of essays about Pre-Texts implementation, for readers who want more information.

But be advised that the information we offer, in publications and on our website (www.pre-texts.org) is an invitation to join us in a literacy campaign that is as urgent in the United States as it is throughout the Americas and much of the developed and developing world. Unstoppable immigration means that literacy will be a bilingual project in economically advanced countries. Education can hope to integrate newcomers with natives if it engages home languages in the host lessons. A literacy campaign would make good on the educational legacy of Latin America (from Mexico’s Vasconcelos to Castro’s Cuba and the Sandinistas’ Nicaragua) for the general benefit of the world. In the matters of art-making, literacy campaigns, and the sheer love of good literature (exemplified by tobacco workers who demanded to hear the greats while they worked) Latin America should be recognized as a model and maestra.

For related material, check out these links:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u4bKkYMQxdo

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S91ylfh0Zqg

Related Articles

Ghosts of Sheridan Circle

Targeted killing of political enemies—assassinations—is thankfully rare in the United States. The most famous such assassination occurred in Washington, DC. And it was committed by a close ally of the United States. In September 1976, Chile’s Pinochet dictatorship…

Bilingualism: Editor’s Letter

It was snowing heavily in New York. It didn’t matter much to me. I was in sunny Santo Domingo with my New York Dominican neighbors on the Christmas break from school. I learned Spanish from them and also at the local bodega, where the shop owner insisted I ask…

Two Wixaritari Communities

English + Español

I first arrived in the wixárika (huichol) zone north of Jalisco, Mexico, in 1998. The communities didn’t have electricity then, and it was really hard to get there because the roads were simply…