Border Crossings in my Boston Cuban Kitchen

Making Ensalada de Nopalitos

Deep in the middle of a Boston winter, depressed by the frigid temperatures and the early descent of darkness, I go to the Jamaica Plain Hi/Lo market for a total immersion in the warmth of an equatorial latitude. Jamaica Plain is Boston’s most freely integrated community, and the Hi/Lo satisfies my soul’s longings for the fluid rhythms of every version of Spanish, friendly faces from every shade cast by our many meztisajes in the Americas. At first I went there seeking the familiar Caribbean shades of brown and its distinctive, percussive Spanish. I mostly bought my familiar repertoire of ingredients: Goya Adobo salt, heavy on the comino, which I learned from my Polish grandmothers to use not only in all my Cuban recipes but also to season my holiday flanken; roast pork at $1.09 a pound called pernil Puerto Rican style but offering a totally presentable Cuban lechon asado for my winter parties. The HiLo stocks 10 pound bags of black beans, the massive, satisfyingly moist avocados (the California crowd calls them watery), the selection of frozen or fresh yuca, the industrial size bottles of cumin, and occasionally even fresh naranja agrias, or sweet/sour oranges.

The resonance of these deeply familiar ingredients reassured me that even in Boston I could still make my home fragrant with the cooking smells of my long lost and much missed Cuba. Soon, though, my cook’s curiosity about the productos Centro Americanos began to overtake me, and I wandered slowly up each and every aisle, stopping to ask the friendly shoppers who surrounded me just what one might do with, for example, the fresh green chayote squash or the white and yellow cracked corn. Right next to the king-size cans of Jalapeño peppers, I found a large can of sliced nopalito cactus, and brought one home to investigate.

Only once, some years before, in my first marriage to an assimilated North American Jew and what felt truly like another lifetime, I was shopping in an Anglo high-priced fruit and flower shop and had found fresh nopal nestled among the high-priced baby vegetables and exotic mushrooms. Nopal is the flat round cactus with the nearly invisible little spines the intrepid but ignorant cook, like myself, fail to see until we have seized it with greedy curiosity in an ungloved hand. After I finished picking out the tiny but sharply penetrating spines out of my hands with tweezers, I did not add them to my fresh avocado and tomato salsa as I had planned (I was in the middle of cooking for 150 soon to be arriving guests and I could not afford any more time- consuming mishaps). But I remained intensely curious, if somewhat more cautious, about what I might do once I safely got my hands again on such an exotic vegetable. Between marriages, my spiritual journey brought me to the Sonoran desert where I saw the wondrous variety of cactus and gained respect for its many versions of sharp spines protecting its hidden riches.

The sliced can on the Hi/Lo shelf seemed like a safe introduction for the now more cautious but incorrigibly curious novice, and I eagerly brought the nopalitos home to try again. This time, opening the can, I learned that once the skin and spines had been removed, the nopalito slices were green and slippery, a little slimy like okra, tender yet dense and resilient to the bite. They always came canned with some salt and jalapeño peppers, so that the slight fire of the peppers gave them an extra warmth. I had already composed fresh tomatillo salsas, as I had discovered their tart green explosion of flavor hidden under their loose brown paper wrapping, and had added them to a bowl with fresh ripe red tomatoes, my favorite Florida avocados, finely chopped green, red and yellow peppers for their vivid color and variegated shades of sweetness, finely chopped red onion for the contrast of burgundy and white and softened sharpness, all of it of course flavored with plenty of garlic, lime juice and the bright verdant vibrance of finely chopped fresh cilantro.

The nopalitos, once I understood their extraordinary gifts of flavor and texture, called for equally exceptional company to honor their presence. Already enchanted with what cilantro and garlic could do for sauteed shrimp, I decided to include garlic and bay leaf steamed shrimp in a reconfigured salsa which the nopalitos transformed into a more substantial salad. Now, the vegetables in my old salsa could be chopped somewhat larger, the peppers still thin sliced but now longer, the tomatoes in slightly chunkier wedges, so they could accompany in size and make contrasts in texture to the slithery slivers of nopal and the firm coral colored shrimp. Something in my tribal wanderings deeply remembers the desert by the sea. Something in my soul is profoundly satisfied by the resulting salad with its echoes of ocean and sun’s fire awakening a great thirst to be quenched by the hidden potable waters of the cactus. The nopal’s riches are so much more rewarding because they must be so respectfully sought.

Boston is a small town full of tribal wanderers who land on her shores and tend to stick with their own kind. Yet as Latin@s have arrived in Boston, first the Puerto Riqueños and Dominicanos with a few Cubanos and increasingly the Centro Americanos, we have realized that there are far too few of us to live in enclave communities with neither cultural nor political links. At the University of Massachusetts in Boston, the working class commuter campus where I teach, I am part of a Latino coalition which recognizes both our community’s diversity and our many connections. When I brought my Nopalito salad to one our parties, the Mexicanos sighed in recognition and all the rest of the gathering–Puerto Riqueños, Salvadoreños, Cubanos, Dominicanos, Chilenos, Argentinos–sighed with the pleasure of a new discovery. The salad was the first item to vanish from the buffet table, and has become a new tradition for my big winter parties, each bite warmed by desert heat and cooled by desert waters.

Spring/Summer 2001

Ester Rebeca Shapiro Rok, (aka Ester R. Shapiro Ph.D.), Associate Professor in Psychology and Research Associate at the Mauricio Gaston Institute at University of Massachusetts at Boston, is is a DRCLAS affiliate. Coordinating Editor and co-author of Nuestros Cuerpos, Nuestras Vidas, the Spanish language version of Our Bodies, Ourselves, she is also well-known to visiting poets and scholars from the Caribbean as the most excellent cook of an exquisite lechon asado.

Related Articles

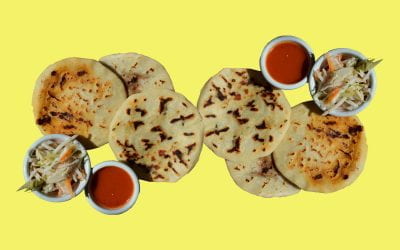

Salvadoran Pupusas

There are different brands of tortilla flour to make the dough. MASECA, which can be found in most large supermarkets in the international section, is one of them but there are others. Follow…

Salpicón Nicaragüense

Nicaraguan salpicón is one of the defining dishes of present-day Nicaraguan cuisine and yet it is unlike anything else that goes by the name of salpicón. Rather, it is an entire menu revolving…

The Lonely Griller

As “a visitor whose days were numbered” in Buenos Aires, Argentina, he tossed aside dietary restrictions to experience the enormous variety of meat dishes, cuts of meat he hadn’t seen…