Boricuas vs. Nuyoricans—Indeed!

A Look at Afro-Latinos

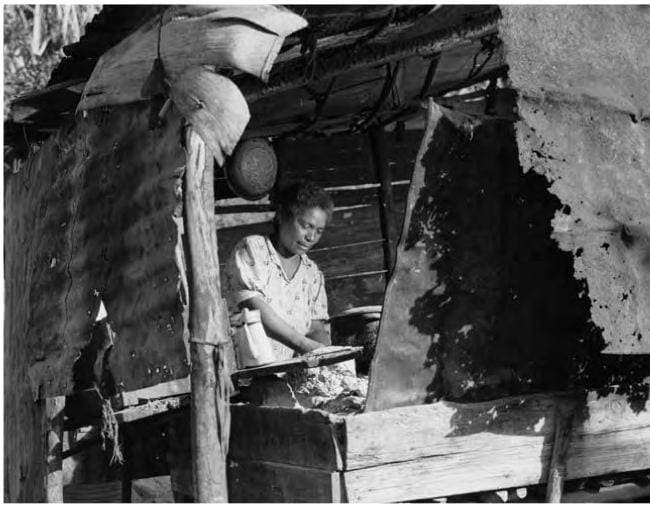

Photographs in a controversial video feature smiling fair-skinned beauty contest winners and fashion models contrasted with images of scantily dressed, full-bodied, dark-skinned women in public spaces—”evidence” of the cultural and aesthetic differences between “real” Puerto Ricans and those who make illegitimate claims on that identity.

These are the verbal and visual claims of a controversial video making recent rounds on the Internet, explaining the alleged differences between Puerto Ricans on the Island and those in the United States. The two-minute video, which has repeatedly been yanked from YouTube, informs the viewer that “Puerto Ricans come from the island,” are overwhelmingly “blancos” or mestizos of Taíno and European ancestry, and “typically VERY classy and/or preppy or as we say in Puerto Rico ‘fino’.” Island Puerto Ricans are also highly educated, the video asserts. In contrast, Nuyoricans are “3rd or 4th generation Puerto Ricans that are usually mixed with African Americans, CAN NOT speak Spanish or speak it very badly!!! They act very, very trashy and ghetto or as we say in Puerto Rico cafre!!!” Nuyoricans are Afrocentric and one is more likely to find them “in prison than in college.” Indeed, Nuyoricans—a misnomer since it encompasses the entire Puerto Rican diaspora—often seem to be a target in this video and beyond for anti-Afro-Latino sentiment. Nuyoricans come under fire for their apparent obsession with race and racism and, most particularly, their identification with African-Americans and blackness.

I first encountered this view of Nuyoricans decades ago when I followed my parents’ dream and took the guagua aérea back to the land of my birth. I quickly learned that to be from the States was to suffer from a social disability, a condition that the island-bred believed I had best overcome for the good of the Puerto Rican nation, if not my own accommodation. That was in the 1970s, when Puerto Rico was being invaded by a seeming horde of return migrants. The children of the diaspora were already perceived as a problem, one that taxed the island’s already scarce resources and presented perspectives that seemed antithetical to long-cherished ideas about Puerto Rican identity. Throughout my many years living and working in Puerto Rico there was rarely a reference to los de afuera that wasn’t, on some level, derogatory, so that even compliments (¡Ay, pero tu no pareces ser de allá! ) only reinforced this sense of undesirable otherness.

The image of Nuyoricans as immoral, violent, dirty, lazy, welfare-dependent, drug-addicted felons was not restricted to the United States; to this day, both countries produce media images that depict stateside Puerto Ricans as overwhelmingly engaged in some type of objectionable behavior. Even by the most sympathetic of accounts, it’s assumed that living in what José Martí referred to as the “entrails of the monster” ruins Puerto Ricans, robs them of language and culture, and leaves them susceptible to destructive foreign influences.

One aspect of this alleged foreign influence is the Nuyorican attitude toward race. Yet many foreign ideas have found fertile ground in Puerto Rico. For instance, despite initial skepticism about the feminist movement, by the late 1970s, the Island boasted a number of feminist organizations, as well as the official endorsement of the Commonwealth government. At the Comisión Para los Asuntos de la Mujer, for example, programs and literature developed in the United States barely underwent any alteration in their transfer to Puerto Rico; most were merely translated into Spanish. Not only were these “foreign ideas” acceptable but so too was the format—neither message (middle-class feminism) nor messenger (in the main, white women) met with the easy dismissal affected against Nuyoricans who talked about race and racism. Nor were those islanders who espoused the new ideas about women’s place in society any more receptive to the new ideas about race than was the general population. Thus, when I described my own research on racism in Puerto Rico to the then—director of the Comisión, I was assured that “we don’t have such problems here.” Little wonder, then, that more than twenty-five years after Isabelo Zenón Cruz published his biting exposé on racism in Puerto Rico, Narciso descubre su trasero, there is still no official acknowledgment of its existence on the island. Newspapers, magazines and the broadcast media continue to ask if racism exists, rather than acknowledging that it does, a tactic followed by the island’s Civil Rights Commission in its rare publications on the subject. Nor is it surprising that Black Puerto Rican women, so long ignored as women and as Blacks, found themselves compelled to establish their own organization, La Unión de Mujeres Puertorriqueñas Negras, as a vehicle for fighting the silence, invisibility and abuse that marks their participation in la gran familia puertorriqueña.

This reluctance to engage racism as anything other than an imported “gringo” problem is consistent with the exceptionalist posture typical throughout Latin America, where the myth of racial democracy has continued to dominate national discourse despite well-documented evidence to the contrary. Puerto Rico, identifying as culturally “Hispanic,” has looked for its models to an increasingly Europeanized Spain and to other Spanish-speaking countries. The prevalent tendency is to ignore the neighboring Caribbean islands, full of “negros de verdad,” and instead to focus on aHispanoamérica ostensibly full of mestizos, indios and blancos—all bound by the same reluctance to acknowledge its strong African roots.

Puerto Rico as a “Latin” country exempts itself from racism even as it distances itself from its Blackness, identifying “real” Blackness as somehow inconsistent with Hispanic history and culture—or with history and culture, more generally. This perspective has become the official line, made real by repetition rather than concrete experience or the historical record. The contradictions have provided space for and encouraged the creation of a Taino revival movement overwhelmingly composed of second and third generation stateside Puerto Ricans who, by laying claim to indigeneity and thus the most “original” roots, propose to out-authenticate the islanders. It is a view that leaves unexplained why a people ostensibly so proud of their racial mixture overwhelmingly reject mixed race classifications. Revealingly, and to the consternation of many, more than 80% of islanders self-identified as white in the 2000 census.

It is to this white identity that our amateur video-maker pays homage, citing census figures and the mitochondrial-DNA studies of University of Puerto Rico biologist Juan Carlos Cruz Martínez to buttress his argument that “real” Puerto Ricans owe their genetic and cultural mestizaje to European and indigenous peoples. And it is this understanding of a de-Africanized mestizaje that many Puerto Ricans cling to when they first arrive in the United States.

It permits a scenario in which Puerto Ricans, defined as neither Black nor white, arrive in the United States devoid of racial prejudice only to be accosted by it in their new home. Puerto Ricans are presumably taught racism in the U.S. and forced to choose between Black or white identity, to the detriment of their “true” cultural selves. This perspective, prevalent in the scholarship produced since the 1930s, is also expressed in the autobiographical novel Down These Mean Streets, the dark-skinned Piri Thomas anguishes over being “caught up between two sticks.” Yet, it would be more accurate to say that Thomas and the others are actually stuck between the myth of racial democracy with its implicit preference for a bleached mestizaje, and the reality of African descent as a liability. The choice, if choice there were, is not between Black and white but between the myth of race-free color blindness and the reality of anti-Black racism. It is this fundamental contradiction that provided fertile ground for new ways to understand race.

The generation that came of age in the 1960s and 1970s saw what earlier migrants have seen from the beginning of the Latino presence in the United States. Since the turn of the century people such as bibliophile and historian Arturo Alfonso Schomburg have confronted overt racism. However, the open acknowledgment of its existence, also provided the political space to fight against racism. The shared experiences of racial discrimination and the concrete conditions flowing from it—deficient educational, health, and employment opportunities—confronted the more subtly phrased, but no less destructive ideology of racial democracy, learned from our parents and our community, and it became clear that something was off kilter. The very language of racism—”pelo bueno,” “pelo malo,” “Negro pero inteligente,”—which we heard in Spanish andEnglish, left little doubt that the similarities between us were actually greater than the differences. The anti-racist, egalitarian ideas that flowed from the Civil Rights movement affected all those in the United States who were racially subordinated—African Americans, Puerto Ricans, Mexicans, Native Americans, Asians, etc.—in the United States and throughout the world. Nuyoricans were particularly receptive to the ideas and values that arose from these struggles because, located at the very bottom of the social and economic hierarchy of the City, they realized that it is of crucial importance to give due attention to the role of race in our lives.

The effect of the US antiracist movement on Puerto Ricans in the island has received less attention but there is ample evidence of those influences. It extends far beyond the short lived trendiness of the African-inspired dress and hairdos or the continuing fascination with the musical innovations that we know as “salsa” and reggaetón, or even the growing intellectual interest in identifying the African influences—or, at another level, foundations—of Puerto Rican culture. Less obvious, or at least less commented upon, is the effect on the educational life of Puerto Rico, where the astounding growth of post-secondary educational institutions on the island can be directly attributed to programs implemented under federally-mandated Affirmative Action guidelines. Inter-American University, Sagrado Corazón, and the countless technical colleges that opened their doors in the 1970s were able to develop precisely because all Puerto Rican students—whether on the island or in the States—qualified for federal assistance programs. Yet even as Puerto Ricans, especially on the island, rejected the stigma of racialization, they still accepted—indeed, actively sought out—the benefits of this racialization. That so many of the beneficiaries have often been the children of the more economically privileged sectors of our various communities does not diminish the significance of those race-based reforms. At the same time we would be remiss if we ignore the ways in which ideas about race and class continue to influence the actions taken by university admissions officers, corporate boards—and disgruntled video-makers.

But of even greater importance for those concerned with social justice has been the steadily growing chorus of voices raised against the Latino myth of racial harmony. For decades, stateside Puerto Ricans have been among the most active supporters of the Afro-Latin@ movements in Latin America and the Caribbean. In recent years the transnational dimension has gained momentum as Black Latin@s, and those who simply affirm their African ancestry, have organized in cities across the U.S. and across national borders. In addition to university-based organizations and cultural institutes, grass-roots groups such as The Afro Latin@ Institute of Chicago (ALIC), ENCUENTRO in Philadelphia and ENCUENTRO “Voices of AfroLatinos” in Boston are working to bring visibility to issues affecting African-descendant Latinos. Such efforts are also taking place on the island; in defiance of the silencing ideological and psychological controls of the rainbow/mixed race nation construct a group of people in the towns of Aguadilla and Hormigüeros (“Testimonios afropuertorriqueños: un proyecto de historia oral en el oeste de Puerto Rico),” have joined forces to “pursue a collective agenda so that Afro-Puerto Ricans no longer remain at ‘the bottom of the barrel.’” Black Puerto Ricans are demonstrating that when it comes to class and race matters it’s definitely not a question of Boricuas versus Nuyoricans.

Spring 2008, Volume VII, Number 3

Miriam Jiménez Román is director of afrolatin@ forum, a research and resource center focusing on Black Latinos and Latinas in the U.S. She was the Managing Editor and Editor of Centro: Journal of the Center for Puerto Rican Studies. For over a decade, she researched and curated exhibitions at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, where she also served as the Assistant Director of the Scholars-in-Residence Program. Currently a visiting scholar in the Department of Social and Cultural Analysis at New York University, she is co-editor (with Juan Flores) of Afro-Latinos in the United States: A Reader (Duke University Press, forthcoming).

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter: Puerto Rico

Long, long ago before I ever saw the skyscrapers of Caracas, long before I ever fished for cachama in Barinas with Pedro and Aída, long before I ever dreamed of ReVista, let alone an issue on Venezuela, I heard a song.

God Needs No Passport

For a practicing Buddhist, my first Mass attendance at St. Ambrose two years ago was a memorable event. I had spent the earlier part of the day visiting…

Blood of Brothers: Life and War in Nicaragua

Stephen Kinzer, New York Times Bureau Chief in Nicaragua for most of the war years, pauses in his compelling account of the war and its politics to explain the Socratic method needed to give…