Brazilian Amazon at a Crossroads

Photos by Tommaso Protti for the Foundation Carmignac

The first time I traveled to the Brazilian Amazon some years ago, I visited my friend Simone in Macapá. The capital of Amapá, one of the nine states that make up Brazil’s Legal Amazon region, Macapá is a sleepy town on the northern bank of the Amazon River, close to where it meets the Atlantic Ocean. As I hovered over the line of the equator that cuts through town, one foot in the northern, another in the southern hemisphere, I was told that eggs standing on the division will not fall to either direction.

JENIPAPO, BRAZIL – JANUARY 30, 2019: Paulo Paulinho Guajajara (25), a member of the Guajajara forest guard at the Araribóia indigenous reserve in Maranhão state. For several towns in the surrounding region, the local economy is based largely on illegal timber and irregular sawmills provide jobs for poor, unskilled workers. Indigenous activists who confront logging interests routinely suffer harassment, threats and even murder.

Admittedly, my guide for the day had not actually tried the experience, but she seemed convinced of its veracity.

I remember thinking at the time that the Amazon was like one of those eggs, strong but vulnerable, hanging in a precarious balance. Would it yield to the pressure of unbridled economic development, beaconing with the promise of an elusive El Dorado? Would it listen to the voices of those Indigenous, riverine and Quilombola (former runaway slaves) peoples who have inhabited the land for centuries? Would it even survive climate change, increasing desertification and the alarming rate of species extinction the earth is currently going through?

A few years later, the Brazilian Amazon, which amounts to 64% of the rainforest, is definitely out of kilter. Deforestation had been on the rise since 2012, but after President Jair Bolsonaro took office in January 2019, forest destruction has expanded dramatically. July 2019 saw a staggering 278% increase in deforestation when compared to the same month the previous year and predictions do not bode well for 2020. Data for the first trimester of this year shows a record rise of deforestation alerts, growing by more than 51% when compared to the same period in 2019. The Covid-19 pandemic has emboldened illegal loggers and miners, aware of the fact that Indigenous peoples are more vulnerable to the disease and, therefore, less likely to patrol their lands for fear of contagion. As the dry season (July-December) sets in the region, we are likely to see a repeat of last year’s destructive forest fires that caught the world’s attention and drew widespread international condemnation.

Spring/Summer 2020, Volume XIX, Number 3

- GRAJAU, BRAZIL – SEPTEMBER 14, 2018: A deforested area in the southern Maranhao state seen from the helicopter of IBAMA, Brazil’s national environmental agency. Maranhão is one of the worst affected by forest fires and illegal logging that has lost 75 per cent of it’s Amazon forest cover. The Amazon Rainforest is losing a football pitch of forest cover every minute. Scientists say the Amazon is reaching a tipping point: if deforestation continues upward, the forest may never recover.

- JACUNDA NATIONAL FLOREST, BRAZIL – AUGUST 27, 2019: Burned fields near the Jacunda National forest in the Rondonia state. More than 80,000 fires have broken out in the Amazon rainforest in 2019. Fire is used in traditional farming practices to replenish soils after crops have been harvested. But often, with strong winds, the fires spread out of control and destroy forests and vegetation. This is a problem that scientists say is getting worse with the extreme weather conditions of climate change where dry seasons are becoming more intense and extended. Illegal land-grabbers also destroy trees so they can raise the value of the property they seize.

Fines for environmental crimes are at their lowest for decades since Bolsonaro took office. In a recording of a governmental meeting recently released by a court order, Brazil’s environmental minister Ricardo Salles is heard advising other members of the executive to take advantage of the media attention afforded to Covid-19 to surreptitiously pass laws deregulating environmental protections. Encouraged by the government’s lenient approach to—and often outright incitement of—deforestation, incursions into protected areas and Indigenous lands are rampant.

Once trees are cut by loggers or simply burnt to the ground, the forest is, more often than not, turned into monoculture plantations like that of soybeans or grassland to feed the lucrative Brazilian cattle ranching business. The power of the agribusiness lobby in the Brazilian congress was already responsible for overhauling Brazil’s forest code in 2012. Among other changes, this meant granting amnesty to those responsible for illegal deforestation before 2008 and reducing the protected areas of forest in the country.

- ARARIBOIA, BRAZIL – FEBRUARY 01, 2019: A member of the Guajajara forest guard in a moment of of sad silence at the sight of a toppled tree cut down by suspected illegal loggers on the Araribóia indigenous reserve in Maranhão state. With deep cuts to Brazil’s environmental and indigenous protection bodies in recent years, tribespeople across the Amazon are increasingly forming vigilante groups to protect their lands against unscrupulous farmers, loggers and land grabbers. But it’s dangerous work. Indigenous activists who stand up to powerful interests in Brazil’s Amazon states are routinely threatened, persecuted and murdered.

- JAMARI NATIONAL FOREST, BRAZIL – MAY 19, 2019: Illegal timber seized in the Jamari National Forest in Rondônia state which is constantly targeted by illegal loggers. Once the loggers have removed the wood from the forest, it’s taken to nearby irregular sawmills. Using falsified documents, it’s then sent to Brazil’s industrialized south or abroad to Europe, China or the United States. Deforestation is on the rise again in the Brazilian Amazon, after successive years of fall, following deep cuts to environmental protection agencies.

The destruction of the Amazonian rainforest is a tragedy for the people who have lived off the land long before European settlers arrived. The region was home to several million Indigenous peoples at the time when the first colonizers reached the river, a culturally and linguistically diverse population that was reduced by disease, enslavement, cultural colonization and loss of land to little more than 200,000 people by the 1980s.

With the end of the military dictatorship and the introduction of legislation protecting both the forest and its people, Amazonian Indigenous groups and their cultures started to rebound. They are now again under threat. Their demarcated reserves are invaded, the trees cut down and the forest burnt, forcing many to patrol their lands, which often results in violent clashes with loggers and farmers. The Pastoral Commission for the Land, part of the Brazilian Catholic Church, has counted more than 600 assassinations linked to land disputes since 2003. The majority of these killings are of Indigenous peoples and other traditional inhabitants of the Amazon rainforest fighting against illegal landgrabs.

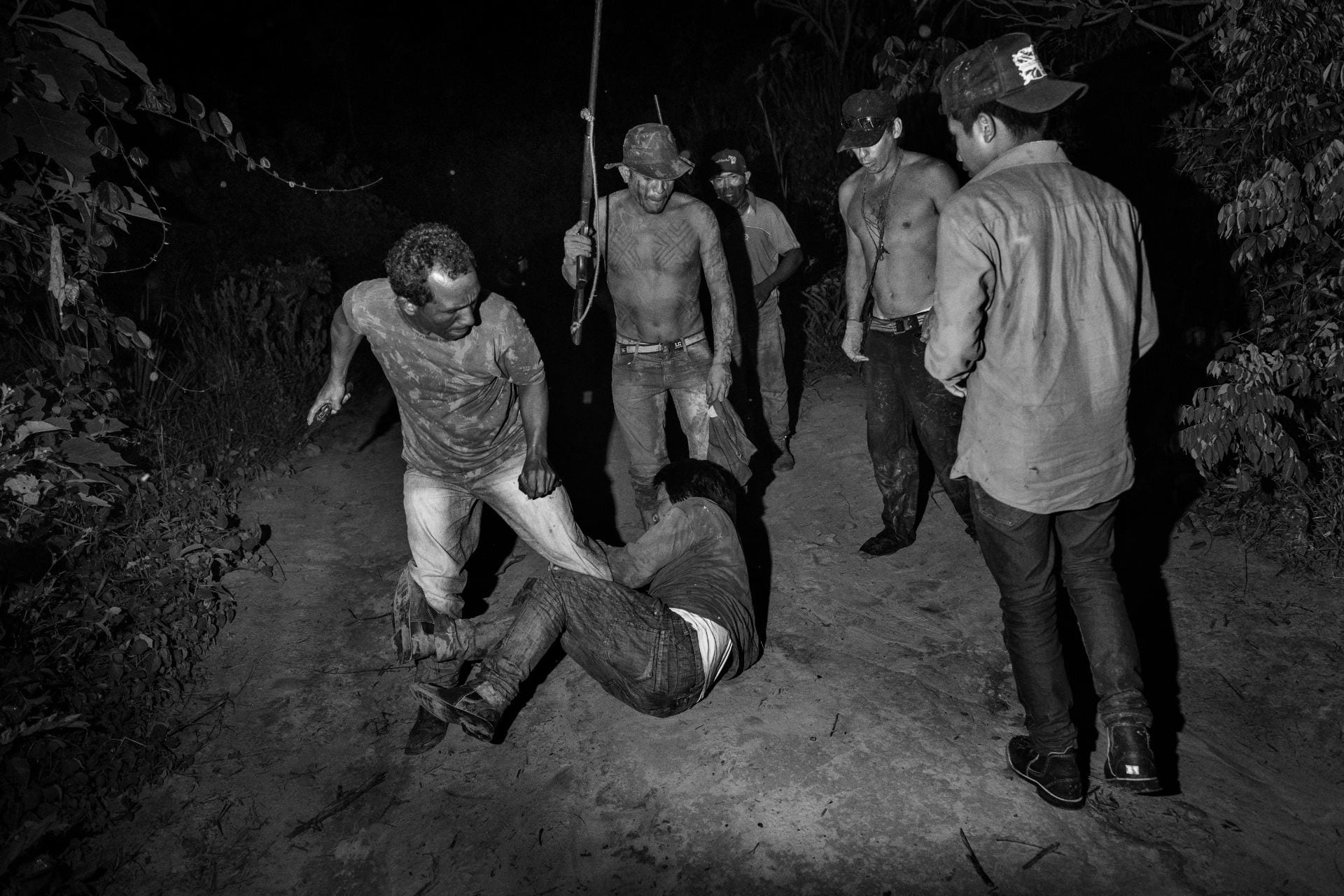

- ARARIBOIA, BRAZIL – JANAUARY 30, 2019: Members of the Guajajara forest guard patrolling the Araribóia indigenous reserve in Maranhão state beat another indigenous man who they suspect of collaborating with illegal loggers. The guard conducts thorough patrols of their vast indigenous reserve each month, destroying loggers’ camps and seizing equipment when possible. Sometimes, they catch the loggers red handed, which can be dangerous as both groups are armed. In Maranhão and other Brazilian Amazon states, the vast majority of killings over land or resource conflict go unsolved.

- MANAUS, BRAZIL – APRIL 17, 2019: A young man lies dead in the streets of a poor neighbourhood in Manaus, as family members, neighbours and police wait for authorities to collect the body and take it to the morgue. The victim was shot in the head outside of his home. Police and residents suspect the killing was over unpaid drug debts. Manaus has become one of Brazil’s most violent cities. According to local authorities, the majority of homicides are drug related.

In the past one hundred years, one fifth of the Amazon has been deforested. Scientists fear that an increasing deforestation rate might lead the rainforest to a tipping point, after which it would be unable to recover. A significant decrease in primal forest causes the temperature in the river basin to rise, leading to severe droughts. These changes, in turn, weaken the trees, which become unable to recycle as much water, creating an unending vicious cycle. Once a certain threshold is reached, the forest will start shrinking by itself and transition in a few decades to a savannah-like landscape called “cerrado,” already prevalent in drier areas of Brazil, south of the Amazon.

The disappearance of the Amazon rainforest would be disastrous, first and foremost, for those Indigenous and other peoples whose livelihood depends directly upon the forest. But the consequences of such a momentous loss would be much more far-reaching. The Amazon regulates the climate of much of South America, creating aerial corridors of humidity that bring much-needed rain to Southern Brazil and Argentina. Without the rainforest, Brazil’s position as an agribusiness powerhouse would simply not be tenable, as expenses with irrigation would render many crops unprofitable. Beyond leading to a disastrous loss of plants and animals, the end of the rainforest would also release billions of tons of carbon and other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, thus speeding up the process of global warming and species extinction already well under way.

- CANAA DOS CARAJAS, BRAZIL – NOVEMBER 29, 2018: A landless peasant leader on the Grotão de Mutum landless peasant camp near Canaã dos Carajás, Pará state. Brazil’s Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra – Landless Worker’s Movement, or MST – fights for agrarian reform across Brazil where land ownership is extremely concentrated. In Canaã dos Carajás, the group is caught up in a dispute with mining giant Vale which operates the world’s largest iron ore mine, the S11D, in the region. MST is occupying lands that they say Vale bought illegally.

- GOVERNADOR, BRAZIL – SEPTEMBER 08, 2018: A cattle seen at night inside the Governador indigenous territory near the municipaly of Amarante in the Maranhao state. Since the 1960s, the cattle herd of the Amazon Basin has increased from 5 million to more than 70-80 million heads. Around 15% of the Amazon forest has been replaced and around 80% of the deforested areas have been covered by pastures (approximately 900 000 km2). Cattle expansion occurs in the new agricultural frontier areas of the “Arc of deforestation”, from the Eastern Brazilian Amazon (States of Maranhão and Pará), through the Southern Brazilian Amazon (States of Tocantins, Mato Grosso and Rondônia).

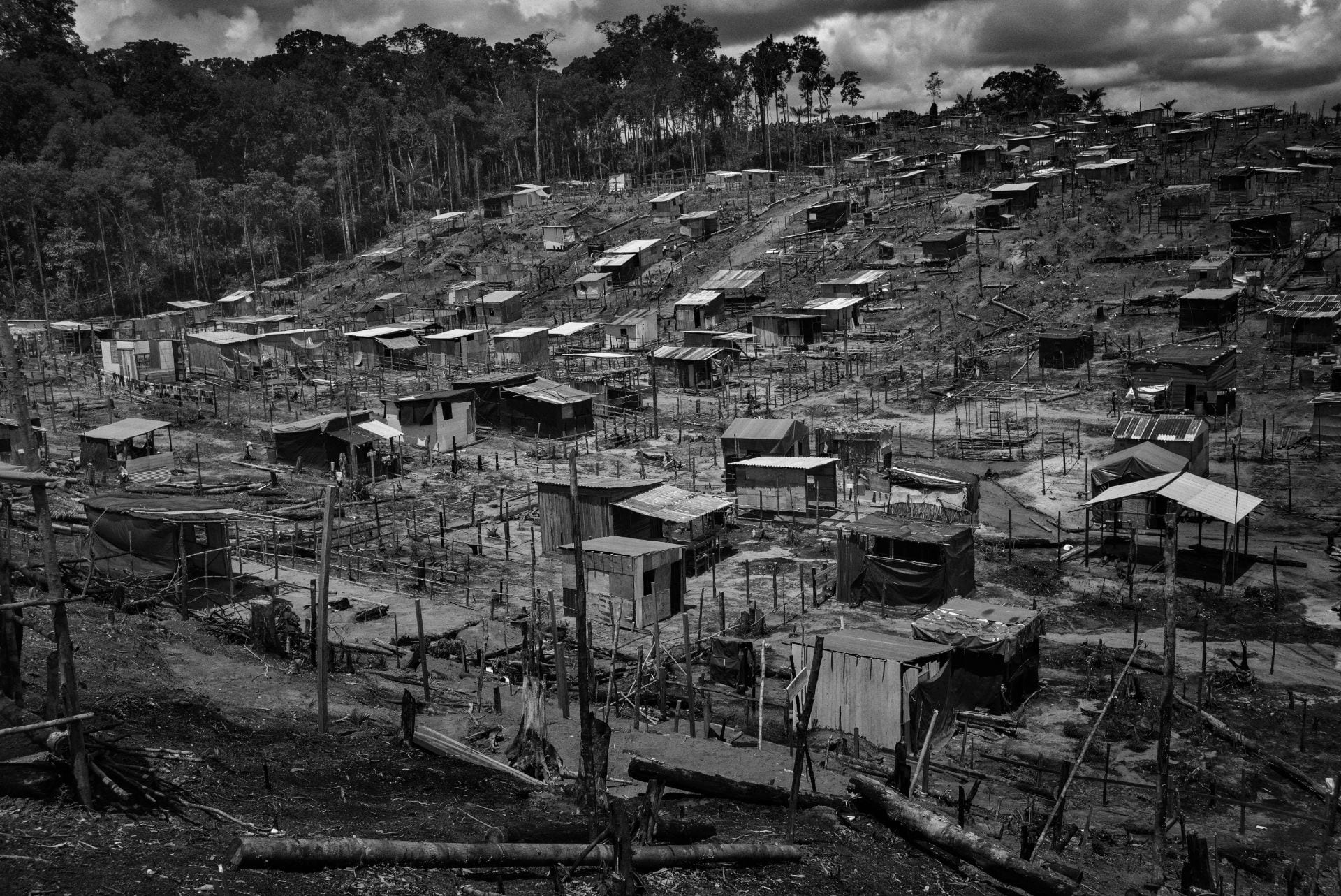

- MANAUS, BRAZIL – APRIL 19, 2019: Hillside view of the Monte Horebe squatter’s community in Manaus. The richest and most populous city of the Brazilian Amazon, every year, Manaus attracts thousands of migrants. Many are fleeing rural poverty and poor public services of isolated interior towns but the city has an enormous housing deficit and as a result, the poorest often end up living in shantytowns on the city’s forested outskirts. Such communities are typically controlled by organized crime gangs and with no environmental oversight, cause deforestation and pollute local rivers.

Robust environmental protection laws should be set in place and protection agencies should be given the financial means to do their jobs. Investment in sustainable economic practices in the Amazon, one of the poorest regions in Brazil, should be a national priority. Were there other ways to make a decent living, illegal logging and mining would not be so widespread. And rather than simply chiding Brazil for failing to curb deforestation, the international community should create substantial financial incentives for Amazonian countries to prevent deforestation, and even reforest already deforested areas.

- KAYAPO INDIGENOUS LAND, BRAZIL – JUNE 22, 2019: An aerial view of the Rio Fresco River, which flows through the Kayapo Indigenous Land in Southern Parà state.

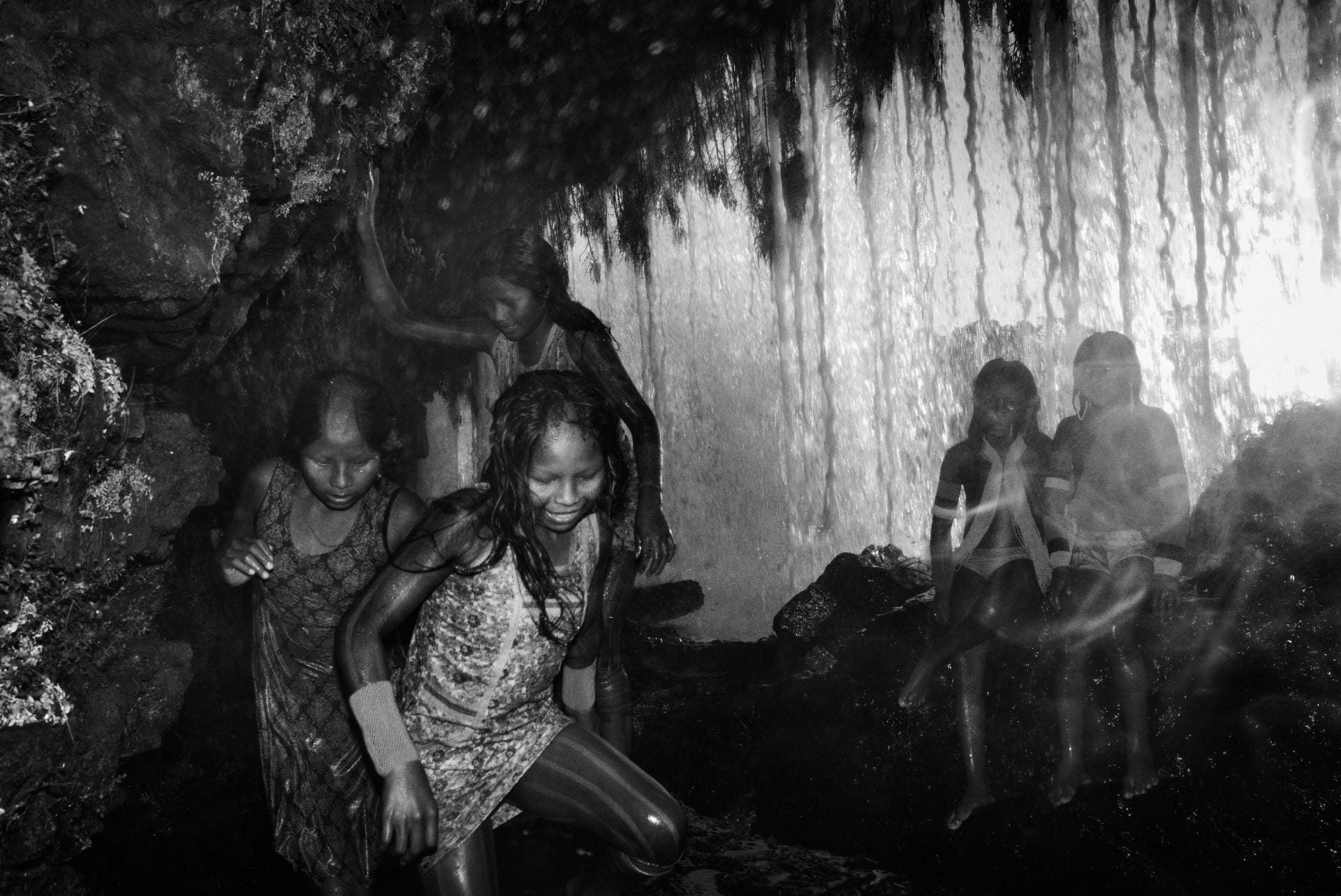

- KAYAPO INDIGENOUS LAND, BRAZIL – JUNE 22, 2019: Kayapo children play behind a waterfall in the Kubenkrãnken indigenous village, in southern Pará state. The Kayapo have only been in contact with non-indigenous society since the 1960s. Their land serves as a crucial barrier to deforestation advancing from the south.

I talked to Simone online a couple of days ago about the current environmental situation in Macapá. “Remember the view of the rainforest from the plane?,” she inquired. “I just flew from Belém the other day and all I could see were cleared patches of land between the trees. If this is happening here, what is taking place further south, where deforestation is supposed to be much worse?” I could hear the sadness in her voice and, even worse, the despondency of knowing that there is little political will for things to improve. But she quickly rebounded back to her usual, determined, optimism: “We will turn things around. If we don’t fight for the Amazon,” she asked, “who will?”

Related Articles

Amazon: Editor’s Letter

The Amazon is burning. The trees that have not been cut down are on fire. The crisis is now. When I began to work on this issue on the Amazon, that was pretty much my vision, and it was a real one. I was determined to make the magazine on the Amazon about…

How Democracies Die

How Democracies Die analyzes the main dangers that modern democracies face. As the authors warn, 21st-century democracies do not die in one fell swoop, in a violent way, by hands that do not always belong to the political system. On the contrary, modern democracies…

The Return of Collective Intelligence

My college Native American Culture professor, the Mescalero Apache scholar Inez Sánchez, told our class that we should regard the word “primitive” as synonymous with “complex.” I gained a better understanding of what Sánchez meant reading The Return of Collective…