A Review of Brazilian Art under Dictatorship

Political Resistance Through Art

Discussions of cultural resistance to the dictatorship that ruled Brazil from 1964 to 1985 tend to focus on two different centers of creative protest. One is the group of musicians affiliated with the Tropicalista movement, especially Gilberto Gil and Caetano Veloso, both of whom are today global cultural figures. The other is the conceptual and performance artist Hélio Oiticica, who invented the term “Tropicália” but died young, at the age of 42, in 1980, just as his renown was beginning to spread beyond Brazil.

In Brazilian Art under Dictatorship, Claudia Calirman, a Brazilian-born assistant professor of Art History at the City University of New York, broadens our scope considerably by examining the work of three other visual artists who challenged right-wing military rule in ways that were both original and playful. Antonio Manuel, Artur Barrio and Cildo Meireles worked in different media, but shared a similar sensibility and approach: “They abandoned traditional forms such as painting and sculpture in favor of ephemeral actions and interventions,” she writes, thereby “challenging the dictatorship while at the same time staying beneath its radar.”

The key word here is “ephemeral.” By avoiding traditional forms, Brazilian artists not only saved money on materials, an important consideration in a country that was then largely poor, but also lowered the risk that the military government and its extensive apparatus of censorship and repression would be able to seize, or even locate or identify, the works that were being created in opposition to the dictatorship. And by producing portable works that were not meant to last, artists could also work outside the structure of museums, galleries and exhibitions like the São Paulo Biennial, all of which were closely watched by censors.

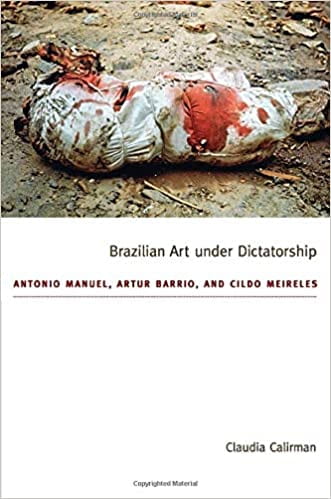

The cover image of Brazilian Art under Dictatorship offers an especially powerful example of this approach. It portrays one of Artur Barrio’s so-called “bloody bundles,” which he created out of a mixture of “garbage, urine, raw meat, spit, saliva, tampons and toilet paper” and dumped in public places. An associate would then photograph or film the disgusted reaction

of passersby and, eventually, the police. “Viewers were meant to perceive these gruesome bundles as lacerated and bleeding human body parts, perhaps even the remains of people tortured by the dictatorship,” Calirman explains, or criminals killed by the official death squads that flourished at the time in Brazil’s large cities.

Cildo Meireles, probably now the most commercially successful of the three artists examined here, took a more sly and subtle approach. In one of his best-known “insertions,” which took place in 1970 at the peak of political repression, he took Coca-Cola bottles, used a silkscreen to engrave anti-American and anti-government messages on them, and then sent them back into circulation, with the messages becoming legible when the bottles were re-filled. In a similar project with banknotes, he stamped political slogans and the names of political prisoners on the backs of bills, making the military regime livid with anger but also showing its impotence. “In today’s terms it can be compared to the actions of Internet hackers,” Calirman writes.

The most durable of the works the three artists created is probably Antonio Manuel’s signature 1969 piece “Soy loco por ti,” discussed at length in Calirman’s book, which recently was voted book of the year by the Association for Latin American Art. With a title derived from one of Gilberto Gil’s songs, the installation, made of a mixture of wood, cloth, plastic and rope, consists of a blood-red map of South America on a black background, with a grass bed underneath the painted map. Censors didn’t like the color scheme, which they saw as advocating Communism and anarchism, but the image became an enduring and popular one, cited repeatedly up until this day. Antonio Manuel, on the other hand, quickly moved on to experiment with other forms, including using his own body or the molds of newspaper front pages, to create less permanent works.

Calirman takes pains to show that the subversive cultural expressions that the three artists personified did not exist in isolation, but were in dialogue with other cross-currents in Brazilian life and culture. One example is the 1928 “Manifesto Antropofágico,” which argued that since the default setting of Brazilian artists is to “devour European culture, digest it, and transform it into something Brazilian,” the natural mode of Brazilian culture is “cultural cannibalism.” In Barrio’s case, she notes affinities between his style and that of the acclaimed Cinema Novo movement of the early 1960s, since both “favored the aesthetics and narratives of poverty” and proudly embraced a “DIY” style in opposition to the culture-as-industry approach of reigning centers of global cultural power.

One particularly compelling insight has to do with parallels between Antonio Manuel’s work and the international style known as “body art,” which emerged around the same time. Outside Brazil, that style was viewed as shocking and transgressive, But “the Brazilian interpretation of body art,” Calirman explains, may have seemed less of a rupture with the past because it “stressed the Dionysian associations of the body through its incorporation of Carnaval festivities,” one of the most quintessentially Brazilian public activities, and “[the Carnaval’s] liberating behavior.” Manuel was also evoking the destruction or degradation of the bodies of political prisoners and criminals through torture, she notes, but he was able to do so in a metaphoric way that would not draw additional official ire.

Calirman’s book also contains some amusing, little-known factual nuggets. Who knew, for example, that the experimental composer John Cage, the leading global exponent of using aleatory elements in artistic creation, “appeared incognito” at the Apocalipopótese, a series of Happening-like events held in Rio de Janeiro in mid-1968, conceived by Hélio Oiticica and featuring work by Antonio Manuel? And it’s hard not to laugh when Artur Barrio, in an effort to be provocative, attempts to qualify for an exhibition in Rio in 1970 by submitting “a handwritten manifesto against the salon’s rules and its jury.” He was outfoxed, however: “When his manifesto was accepted by the jury in the drawing category, Barrio was furious.”

But perhaps the most absurd and revealing of such colorful anecdotes has to do with the fate of Manuel’s “Soy loco por ti.” It was purchased by a Brazilian bank, but when, after two months, “the new owners arrived to pick up the work, it had rotted” and

“was now emitting a bad odor.” The artist himself, Calirman reports, “was nonplussed, deeming it ‘South America itself exhaling its own smell of decomposition.’ The bank paid for the installation but decided not to keep it since it did not know how to restore and preserve it.”

As the Brazilians themselves like to say, “Só no Brasil,” or “Only in Brazil.” From more than 40 years remove, what can we say about the disputatious works these three artists produced and of the moment in which they flourished? Ironies abound. As Calirman notes, “at the end of the day, the government dismissed them as insignificant and irrelevant, no more than anarchic jesters, and much of the mainstream public was unaware of their attempts at transgression.” But today their work, or at least the part that proved not to be ephemeral, is highly collectible—Meireles’ tampered-with Coke bottles, for instance. And some of the photo credits indicate that other works have ended up at the Inhotim Center of Contemporary Art outside Belo Horizonte, a new and internationally celebrated museum which accepts only the best and most significant of modern Brazilian art.

Calirman, who was a 2008-09 Lehmann Visiting Scholar at the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, takes a measured view, being careful not to overstate claims to the importance of what these three artists achieved. “It is impossible to measure the success or failure of their actions,” she writes. “Likewise it is impossible to deny these endeavors’ value as part of a crucial historical moment in Brazil.” At the very least, the works of Antonio Manuel, Artur Barrio, Cildo Meireles and others discussed here demonstrate that “there was in fact robust artistic production during the dictatorship.” Shouldn’t that be enough?

Spring 2013, Volume XII, Number 3

Larry Rohteris the author of Brazil on the Rise. He was a correspondent in Brazil for 14 years, for The New York Times and Newsweek. He is now a cultural reporter for The New York Times, specializing in international arts.

Related Articles

A Tale of Two Flags

A Tale of Two Flags The Last Hurdle When in 1995 President Ernesto Pérez Balladares appointed me to head the commission responsible for the transition of the Panama Canal from U.S. to Panamanian hands, it never crossed my mind that yet another negotiation—unexpected...

Who Remembers Panamá?

There was a time, many decades ago, when the Isthmian country of Panamá—dividing the Americas—made near daily headlines from Canada to Argentina…

The Story That Panamá Decided to Write

A few days prior to the date set for the transfer of the Panama Canal from the United States to Panamá, a reporter from a U.S. news network asked me, “Mr…