Brazilian Cinema Now

Between Plasticity and Blindness

Snow falling in the city of São Paulo, in southern Brazil? Taking a helicopter in São Paulo then arriving a few moments later in the deep wilderness of the Amazon jungle, half a continent further away to the north? Then meeting a white Asian tiger in the heart of the Amazon forest? Returning afterwards to São Paulo to watch martial-arts duels between triad and yakuza-style gang members? One could very well say that none of those things are remotely possible in the real world. Well, but as a matter of fact, they are the very stuff globalization is made of.

These days, instead of trusting your reason or even your instincts, you are rather invited to believe what is shown on a screen. We are living under the influence of the spectacle gone wild. The scenes described above are part of a new Brazilian (?) film, aptly named Plastic City. It is actually a co-production involving Chinese, Japanese and Brazilian investors, casting Asian film stars Joe Odagiri, from Japan, and Anthony Wong, from Hong Kong, under the direction of the renowned and twice Cannes Festival nominee Yu Lik Wei, from mainland China. The Asian associates put in 60% of the investments, leaving 40% for their Brazilian partners. However, the entire budget for the production had to be spent in Brazil, which technically made it a Brazilian film. But is it, really?

Welcome to a new age. Once upon a time there was a rather prestigious tradition called Brazilian cinema. Nowadays what you are going to have will be more and more films made in Brazil. It might sound pretty much the same, but it is not. Some call it globalization, others call it outsourcing, everybody agrees though that local contexts, cultural singularities and historical circumstances need to be erased if your aim is to place a visual product in the world market, designed for indiscriminate consumption. Within this new strategy, the more you neutralize the local flavors, enhancing on the other hand the colors, the elegant display and the fancy glasses, cutlery and porcelain, the closer you get to the shiny gates of success. Just follow the victorious formula of internationally acclaimed new cuisine. Along that path you would eventually get into Plastic City.

Brazilian film producers were in fact among the first to take a step into the huge and highly coveted Chinese market. Rede Globo, the most powerful Brazilian media network, involving publishing, press, radio, recording, video, TV and film productions, was a pioneer in selling its main product, soap operas, to the Chinese. When, after chairman Mao’s death, it sold them “Isaura, the Slave” the show became the greatest hit ever at the local TV. The star playing the main role, Lucélia Santos, turned into a mass celebrity, her visit to China leading to unprecedented degrees of personality worship, even if compared to the revelries of the Cultural Revolution. As a consequence of her success, Lucélia Santos launched her own film production company, Nhock Produções, and, in 2007, in collaboration with China’s Beijing Rosat, co-produced “Love at the Other End of the World,” aiming at a potential audience of two billion spectators.

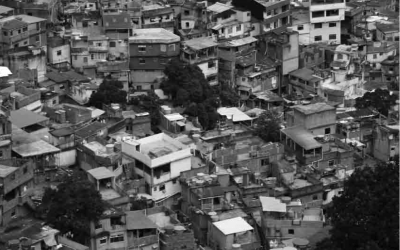

As far as Western screens are concerned however, two other Brazilian films became big hits: The City of God (2002-3), directed by Fernando Meirelles, and Elite Squad (2007), by José Padilha. Although both films enjoyed wide international success, receiving positive reviews and being acclaimed by audiences wherever shown, they could still claim their place as belonging to the tradition of Brazilian cinema. However much they might have tapped into the visual dialects of TV and Hollywood narrative resources, and they did a lot, they nonetheless strived to capture the real social tensions behind the excruciating violence that engulfed the favelas of Rio de Janeiro with the invading swarms of rival gangs trafficking cocaine and crack-cocaine from the 1970s onwards.

In that sense they might have a different syntactic structure and an expressive voice of their own, but they were in line with the critical tradition and political awareness so typical of Brazilian Cinema Novo of the 1960s and 70s. They were both mostly financed by resources collected from local and small film producers, relying on quite limited budgets. Their remarkable success, however, most of all with respect to international audiences, was due less to their ethical stances or political concerns relative to the local and the Brazilian contexts than to their visual impact and the sheer degree of crude violence that they openly displayed.

Neither of the directors subscribed to this rule of fire power imposed by the gangs and the responding police force, but obviously they couldn’t control the reactions of their audiences, least of all outside Brazil. So, regardless of their good intentions, what they intended to show as a tragedy was mostly received as a spectacle, a very amusing one at that, thanks to their striking visual skills and their rather hyperbolic narrative techniques. From that perspective, like it or not, although the films were conceived as Brazilian cinema, they were received mostly as “world cinema,” globalized against their will.

It is quite interesting to follow Fernando Meirelles’ artistic trajectory after achieving celebrity status thanks to the almost universal praise received by The City of God. His most recent film is Blindness (2007-8), based on the book An Essay on Blindness by the Nobel-prize winner Portuguese writer José Saramago. This time the film was a co-production of Brazilian, Canadian and Japanese investors on a grand budget of an amazing US$ 25 million.

The film casts a fine selection of Hollywood stars, among them Julianne Moore, Mark Ruffalo, Danny Glover and Gael García Bernal, plus Japanese megastars Yusuke Iseya and Yoshiko Kimura, and some local talents like Brazilian actress Alice Braga. The film was shot on two different continents, two different hemispheres and in four different countries: Brazil, Uruguay, Canada and Japan. It was granted the rare privilege of being shown at the opening session of the Cannes Festival in 2008. This time, what we have is rather globalization by design.

Even more revealing than this massive convergence of global resources is the effect that such a complex blend of diverse cultural sources had upon the aesthetic configuration of the film itself. The whole work shows a deliberate effort to dispel any concrete references to specific geographic, historic, social, ethnic or cultural background. The title Blindness is meant to suggest a rather wide gamut of blocked senses. Taken straight from José Saramago’s book, the story was devised as an allegory. In many ways it could even be understood as a critique of the detrimental effects of globalization upon local cultures and social bonds in general.

But, once again, good intentions aside, it could as well stress the conclusion that the many processes that lead to cultural dissolution and wrecked communities are so well advanced by now that we have already passed a point of no return. Damage is done, the world as we used to know it is gone for good, as an irretrievable past. Changes were so fast and so huge that they became irreversible. We might not accept it or we might not see it that way yet, but that is because we are all plagued now by a new and particularly morbid form of blindness. Yet, the film tries to unwind a thin tread of hope all along its apocalyptical development—a kind of slim Ariadne’s thread leading our way through the interstices of the global labyrinth.

The story begins with a sequence of scenes showing the complex dynamics of daily life in a huge metropolis: people rushing through the streets, amidst skyscrapers and metro stations, seen in shop windows, climbing stairs, accessing lifts and elevators, surrounded by endless masses of vehicles moving in all directions. Fast camera movements, interspersed with precise cuts, focus on visual signs of diverse nature, lights, colors, poles, posters, letters, drawings, symbols, logos, spots, all the plethora of signals people have to rely on in order to find their way within the chaos of the metropolitan daily rush.

This multiplicity of visual codes reminds us of how much modern life has become ever more dependent on sight and visual orientation, to the detriment of other senses and of our affective needs. Urban order is a coordinated result of rational planning, mechanical discipline of bodies and vehicles, all operating through strict sight-oriented navigation. Rational systems provide the background while visual communications prevail in the foreground in a perfectly integrated network, where human beings are the vibrating molecules that keep the whole hive going.

All of a sudden, an epidemic of blindness falls upon this world order. Disruption is instant and total. Since absolutely everything is dependent on visual orientation, the whole system collapses like a sand castle touched by an unexpected wave. Only then do people realize that they were already blind long before. From within the ensuing chaos, the character played by Julianne Moore emerges as the modern Ariadne. She is the only one who is not affected by the epidemic. She will eventually use her sight to drag a group of people out of the deadly vortex by a rope. They are a group of twelve– a rather symbolic number, like the apostles, the knights of the Round Table, the twelve peers of France, hence a flicker of hope.

To make things more interesting, one could compare Blindness with another film, shot just about a year earlier, The Smell from the Toilet Drain, directed by Heitor Dhalia. It is a local production by a myriad of little independent producers, with an all-Brazilian cast, made with a rather restricted budget, which nevertheless achieved a warm reception among audiences and critics in general. Having been selected for the Sundance Film Festival in the United States, in Brazil it was granted the highest film awards in two of the most important Film Festivals, in São Paulo and Rio. For all these credentials we could consider it as a part of traditional Brazilian cinema, old style. But is it?

Surprise, surprise, it has a lot to do with Blindness. First of all, it is also an allegory that makes a similar effort to erase any solid references to time, place and context. It is rather a comic parody of a sermon, like Erasmus’ The Praise of Folly, except that the evil propensity being chastised here is greed. The story is about the owner of a second-hand shop, who humiliates and abuses the sellers when they come to his office because he knows they are desperate for the money.

More than just buying or trading objects, his pleasure resides in destroying his customers’ sense of dignity and self-respect. Taking for granted that everybody has a price, he wants to shout out loud to his victims how shamefully cheap they actually are. Their degradation gives him the pride of a superior rank, a discriminating mind, a prophylactic mission and a noble destiny. As many others scattered all over big cities, he is a modern Dr Faustus, a master in the business of buying and selling souls.

The camera plays an essential role in these dialogues of degradation. Since the shopkeeper and his customers are seated in front of one another, it is the sight of the powerful buyer which casts down the humble seller. Thus clever camera movements underscore this abject play, by directing the wide-open eyes of the greedy man to the abased countenance of his dispossessed clients. The women are additionally humiliated; he demands that they expose themselves nude to his possessive eyes. At a certain point the shopkeeper buys a large artificial eye, immediately terrifying his victims with his triple sight. Here we have almost the opposite of Blindness, meaning, however, almost exactly the same thing. Reason is equal to sight that is equal to power. Closing the eyes of the shopkeeper for good becomes not only the main aim of all those vilified creatures but also the ethical stance of the film itself.

Although the production of this film is not cosmopolitan, the final product can nevertheless be shown anywhere in the world without losing any of its decisive features or meanings. It is not designed to talk to Brazilian audiences in particular about their concerns, but to world audiences at large, about world dilemmas present and future. Although produced, directed and shot in Brazil by Brazilians, it can travel the world over. In this case, again, it is world cinema made in Brazil, rather than Brazilian cinema. Is this new trend good? Is it bad?

Of course, it is up to the individual to form his or her own opinion about it. What is clear, however, is that when cinema assumes a worldly configuration, it becomes more abstract, more aloof, more thinly shaped into universal parables and empty surfaces. After all, the world is more of a word than a place. Being everywhere is also being nowhere in particular; referring to everybody also misses the concrete living creature. The films and the trends discussed here ring an alarm. Trying to encompass the world as whole into a single scene, as a sublimated Plastic Citysubmitted to the panoptic eye of its globalized camera, cinema risks creating the most monumental ever form of collective blindness.

Fall 2009, Volume VIII, Number 3

Nicolau Sevcenko is a Professor of Romance Languages and Literatures at Harvard University. Formerly a professor of History of Culture at the Universidade de São Paulo (USP), Brazil, and at King’s College, London, Sevcenko works on urban history, race relations, Brazilian Modernism and popular culture.

Related Articles

Coconut Milk in Coca Cola Bottles

Common knowledge has it that virtually any movie, once removed from its original cultural context of production and reception, might be either misunderstood and misperceived or re-interpreted and re-signified. Likewise, we may agree that national cinemas seek to define, challenge….

Neither the Sertão or the Favela

To frame the poetics of the ordinary in terms of subtlety and delicateness is to propose an antidote both for cynicism and for what I call Neo-Naturalism. Its appearance, at least in Brazilian cinema and literature, has been clearly identified, ranging from peripheral subjects…

Oscars for Mexican Filmmakers

English + Español

A couple of years ago, in 2007, the so-called Three Amigos (the filmmakers Alfonso Cuarón, Guillermo del Toro and Alejandro González Iñárritu) went up on stage for the 79th Oscar Awards presentations. Their three films (Children of Men, Pan’s Labyrinth and Babel, respectively)/Hace poco tiempo, en el año 2007, los llamados Three Amigos (los cinerealizadores mexicanos Alfonso Cuarón, Guillermo del Toro y Alejandro González Iñárritu) subieron al escenario de la 79ª premiación del Óscar. En total, sus tres películas (Children of Men, Pan’s Labyrinth y Babel, respectivamente)…