Building Bridges of Cultural Respect

Art and Outreach

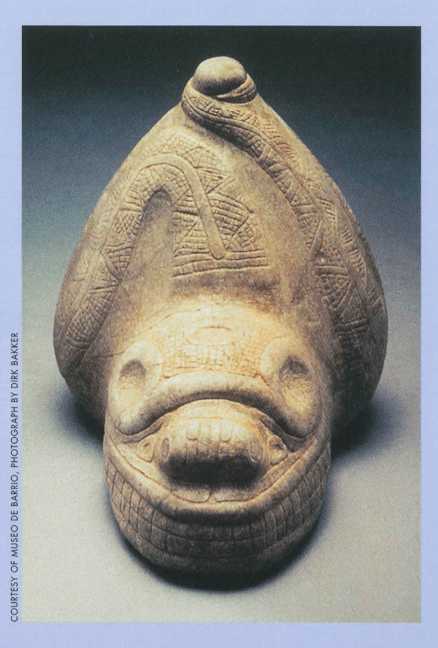

Three-pointer in the form of a serpent stone. (Dominican Republic) Museo Arqueológico Regional Altos de Chavón.

With a recent Master’s degree in Art History and a thesis on French Impressionist artist Gustave Caillebotte, I had set out to search for a position in the art field. Knowing that my family was from South America, a friend suggested I try a small museum in East Harlem, El Museo del Barrio, which had just expanded its mission to include the art of all Latin America. I met with the director, who thought I might be interested in working on an exhibition on Taíno the museum was just starting to develop. I wasn’t quite sure who or what Taíno was, but enthusiastic about Latin American art in general, I said yes.

Three years and many long nights later, I discovered that I was not alone in having been unaware of the fact that the Taíno were the pre-Columbian people from the Caribbean, originally Puerto Rico, Cuba, Jamaica, Haiti and the Dominican Republic. The exhibition I helped organize was the first in the United States to comprehensively study this legacy shared by so many Americans.

It was a huge undertaking for a small museum to bring over 130 artifacts from all over the Caribbean, including Cuba, and from Europe. We highlighted the fascinating culture of the Taínos that flourished between 1200 and 1500. The children and adults who visited the exhibition were moved by the experience often noting how little they had known about their own history and how proud they were to see the sophistication and beauty of their ancestral culture. And others with tremendous knowledge about European and Asian cultures could now see the work of people geographically much closer to our North American continent.

I grew up in New York City in a Spanish speaking household at a time when it was not very common. My parents instilled in me a great pride in our Latin culture. However, the pride I grew up with is not necessarily typical of the present-day first generation Americans. Often this generation has little knowledge of the countries from which their parents have come. I have found that by sharing an understanding of different cultures through the arts, everyone gains a greater self-awareness and an ability to empathize and adapt to a whole array of different experiences. Both first generation Americans and their peers become stronger and more confident through that knowledge.

My experience at El Museo demonstrated how effective outreach into the community could be in forming new bonds of respect and pride between people of different heritages. The comments written by visitors reflected that response: “Before entering the museum I was unaware of how deep my Puerto Rican history was, I’ve never been so intrigued. I also realized that I’ve been taking my culture for granted. Thank you.” And another visitor from a Dominican background wrote: “Thank you. At long last I have been able to participate in an experience that both defines me as a Dominican American young woman from a mestizo ancestry and a member of a culture that has gone unheard. It was both an educational and emotional experience for me.” And finally: “You made us all proud! It’s a wonderful thing our culture is being shown and loved by everyone.”

Recently there has been a lot of discussion about the role and importance of museums. Museums in the United States have always been educational partners and continue to be so. They offer an opportunity for students and adults to leave their environment, ask questions about what art is, how it was made, why it is valued and in a museum. But perhaps the most important issue is how art expresses universal emotions and the imagination we all share, across all financial and cultural barriers it expresses what makes us human. The great museums of the United States were founded in the late 19th and 20th centuries based on the concept that museums should be educational resources. The buildings were to impose dignity and align themselves to the origin of democratic thought, a way of sharing imperial and aristocratic treasures of the past with a broad public.

In a slightly different way, museums of the 21st century enhance our sense of self and create the possibility for a shared consciousness. They have become institutions that reach out and embrace diverse ideas and communities. Museums continue to be vital to our intellectual and cultural life. As the mix in America’s heritage changes, museums have actually become dynamic places where the exchange of ideas and understanding takes place as well as the housing of art.

The Taino exhibition functioned in that way, reaching out to schoolchildren, community members, and even presidents. I would like to end with a quote from a thank you letter from Jacques Chirac for the exhibition catalogue from El Museo:

The Taíno civilization has always been a passion to me, as both fascinating and upsetting. A political, economic and religious society of great richness, it developed an artistic production of great quality. Its quick disappearance, after the Spanish invasion, was no less dramatic. It is thanks to the extraordinary character of these too long ignored and underestimated civilizations that I have been encouraged to go forth to establish a Museum of “Arts Premiers” in Paris.

What a wonderful way to demonstrate how a common appreciation for the art and culture of a proud yet often forgotten Taíno people could form a bond between the President of France and a resident in East Harlem.

Winter/Spring 2001

Estrellita Brodsky, is the vice-chairman of the board of trustees of El Museo del Barrio in New York City. She is presently working on a Ph.D. from the Institute of Fine Arts concentrating in Latin American Art. She is also a member of the DRCLAS subcommittee on Latin American Art. Through this role, she helps to continue to build bridges of cultural respect.

Related Articles

Guatemala Diary

In a deeply personal way, I feel like I am home again. Of all the places I have visited, Guatemala is the country I love and feel closest to. Certainly the most impressive aspect is the persevering Mayan people, who endured a 30-year civil war…

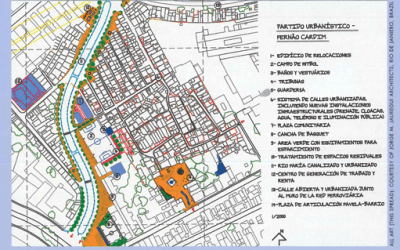

From Favela to Bairro

The Brazilian firm of Jorge Mario J¡uregui Architects is the first Latin American recipient of the Harvard Graduate School of Design’s Veronica Rudge Green Award in Urban Design. The award…

Exploring New Horizons in Latin American Contemporary Art

When I first traveled to Peru by boat with my family fifty years ago, the country seemed as far away from Argentina as Boston from Buenos Aires. My husband had been sent there by W.R…