Buscando America

A Sephardic Pre-History of Jewish Latin America

When I give public lectures about Conversos and Sephardim in the Americas, whether it is in the United States or South America, I always get at least one question, “Columbus was Jewish, right?” Or other times it’s more like a declaration, “We all know Columbus was Jewish.” The statement is generally buoyed by some sort of unexamined pride, as if to say, we the Jews were here from the beginning, we belong, we are American. My listeners generally know that Sephardim are Jews who lived in medieval Iberia from the Roman period to their expulsion in 1492, a date generally associated with Columbus. They may know that conversos are Iberian Jews who converted to Catholicism, some of whom secretly held on to aspects of their ancestral faith. The Sephardim and conversos scattered through the world. But what the audience always wants to know is whether Columbus was a member of that diaspora.

This of course was the reason why Jewish historians at the end of the 19th century and into the early 20th century sought to establish Columbus’ Jewish bonafides while anti-immigrant and anti-Jewish sentiment was rising throughout the United States. It is the same reason Italian Americans claimed the Genoese navigator as their own and established Columbus Day, erecting monuments that proclaimed Italian-American belonging, as a reaction to the suspicion and discrimination that marred their experience in their new land of opportunity.

The study of the Jewish presence in the Americas is often marked by a search for belonging. There is a sense that the Jew is an insider-outsider, one who so quickly absorbs the rhythms and cadence of their new Patria but can never fully let go of or escape their difference. That tension can be very productive but it is also tiring. Contemporary Latin American Jews thus look for ways of laying claim to a patrimony that is not exactly theirs, but neither does it belong to anyone else. In claiming Columbus, contemporary Jews—whose parents or grandparents arrived from Izmir, Bialystock or Tetuán—are rewriting the official narrative to include themselves into the drama of America, allowing them to be both Jewish and American, Cuban, Mexican, Colombian.

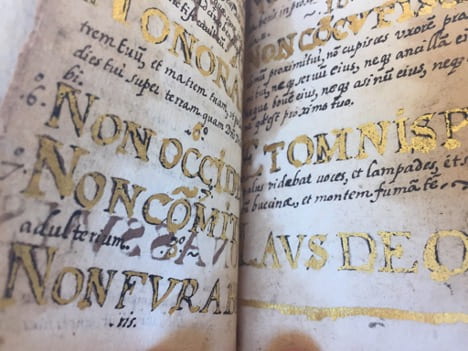

It has been a search for me also. I had the good fortune to get a summer job at the Rare Book Room at the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York City. I had to go through and update the catalog of their Spanish and Portuguese books. My supervisor had low expectations for my project and after a short orientation I was allowed to browse the shelves of this collection and do as I pleased. Among the prayer books with elegant Spanish translations published for conversos who returned to Judaism in places like Amsterdam, Hamburg and London in the 16th and 17th centuries I found many fascinating books: baroque poetry in praise of the grandees of the Sephardic diaspora or long pastoral ballads transporting the reader to a lost arcadia, along with moral and theological works meant to edify the faith of these Jews who only a generation before lived like Catholics back in Spain and Portugal. And among these books I found Pedro Teixeira’s, “ Relaciones de Pedro Teixeira d’el origen descendencia y succession de los reyes de Persia, y de Harmuz, y de un viage hecho por el mismo autor dende la India Oriental hasta Italia por tierra.”

What was this book doing there? Is this a Jewish book in any way? I began to dig into the history of the book and its author. According to one account, this Teixeira is the same Teixeira who after walking on foot from India to Rome (as his books describes) turned his attention to the Amazon River where he became the first European to follow it to its end. I later found out that actually there were two Pedro Teixeiras who traveled extensively, one going to the Amazon and the other to India. The encyclopedia entries, however, cited accounts that described Teixeira as dying in the law of Moses in Antwerp. This possible end of life return to Judaism meant that Teixeira would be claimed by Jewish historians despite leaving no trace of Judaism in his extensive writings and with no documentation of any final embrace of the Law of Moses. So I finally found an account of a converso traveler—albeit one who went to India—but with only a phantom of Judaism hovering over his story.

I turned to a more familiar bookshelf, my father’s. Since I was a boy, I remember seeing a large grey book on the shelf, La Familia Carvajal with a menorah on the cover. What does this Spanish book with the name of a not particularly Jewish-sounding family have to do with Judaism? On break from graduate school, I took it down and began exploring this monumental work of Inquisitorial history by the Mexican scholar, Alfonso Toro. In addition to his sprawling history of this large, complex colonial family, Toro included a transcription of the spiritual autobiography of one of the main leaders of this Converso family, Luis de Carvajal, el mozo. I was mesmerized and I have been thinking and exploring this book ever since. I found the testament to the internal struggles and hopes and dreams of an American converso that I was searching for. Not only does Carvajal describe his journey to Mexico, the hurricane that almost killed him and his brother at Veracruz, his roaming the Deserts of Northern Mexico with his uncle, the Governor of el Nuevo Reino de León, but he uses these physical journeys as a prism for his spiritual exploration.

Winter 2021, Volume XX, Number 2

Carvajal’s text points to the wide-ranging networks of converso merchants whose bonds of blood and shared commercial interests created an intricate community that spanned oceans and political frontiers. People cross over from Ottoman Turkey and Italy, where they can fully embrace Judaism to the lands of “idolatry,” Spain and Portugal and the colonies, all the while connecting with relatives or business associates who may not share the same religious commitments but are all part of an ethnic network that preserves a sense of community, economic vitality and for many a deep, idiosyncratic faith. Carvajal’s uncle and brother Gaspar are devout Catholics but Luis and the rest of his siblings are committed to Judaism to varying degrees. This diverse religious palette was rather common within these families.

Edna Aizenberg, que en paz descanse, astutely coined the term Neo-Sefardismo to describe the way that contemporary Latin American Jews invoke a Sephardic past in order to root themselves more firmly in the Ibero-American soil of their new homelands. By enjoying a Ladino ballad or claiming the Jewish blood of a conquistador or the secret Judaism of a local indigenous group, their Judaism becomes Latinized, giving them access to belonging to an Iberian past through the Sefarad connection.

In Argentine Jewish writer Alberto Gerchunoff’s classic Los Gauchos Judíos, the rabbi back in the Old Country invokes the great Spanish medieval rabbi Avraham Ibn Ezra and the golden age of the Jews in Sefarad while they sit in the heart of an eastern European shtetl. In his spellbinding La Vida a Plazos de Don Jacobo Lerner, Peruvian American author Isaac Godemberg cuts the narrative with excerpts from a Lima Jewish newspaper (an often absurdly funny creation of Goldemberg’s pen). The excerpts feature news of weddings and bar mitzvahs, some local and world news and curiously a series of mini-essays chronicling the Jewish presence in colonial Latin America. In this novel filled with ghosts and Dybukim, Goldemberg weaves in his own literary and historical ghosts to haunt the contemporary story of Jewish immigration and existential misadventures in the New World, rooting his characters in an imaginary Sephardic past that give them the fleeting illusion of belonging.

Colonial literature and history served a similar function for the emerging independent nation states of the former Spanish Empire. From Mexico to Tierra del Fuego, Latin American intellectuals turned to the colonial and pre-Columbian period to establish their young republics on solid historical foundations, as nations with a past and a rich cultural tradition, not mere peripheral stepchildren of empire. The turn towards the past helped invigorate and shape emerging Latin American identities. It served, as Borges would say, as a usable past.

I also turned to the narratives of the colonial period in search of a Sephardic America or at least in search of the footsteps of Jews who passed through the Americas. I knew from many classic histories that conversos came to the New World from the very beginning of European exploration, conquest and colonization. There were conversos on Columbus’ first journey (he signaled out one of them, Luis de Torres his interpreter who could speak Arabic, Hebrew and Chaldean!); there were conversos among Cortes’ men and rumors that Bartolome de las Casas—the apostle of the Indies and defender of the Indians was possibly a converso.

But I also knew that most of the conversos who wound their way to the Caribbean and then later to Terra Firme were devout Catholics with little interest in their ancestral faith. However, a minority was committed to keeping some form of Judaism in secret as they lived their lives under the watchful eye of the Inquisition. There were the accused Judaizers investigated and ultimately punished by the Inquisition which was formally established in Lima and Mexico City in 1570 with a third office opened in 1610 at Cartagena de Indias. The Cartagena Holy Office was set up because of the high volume of contraband being smuggled into South America through that port and others. Much of this trade was in the hands of Portuguese merchants, many of whom fit the profile of the converso. I knew these people were there. They encountered the astounding natural beauty and ferocity of the tropics and the Andes; they engaged with the variety of indigenous peoples and cultures which held up a mirror to the culture and values of the Old World; in short, these conversos were part of that great encounter and I wanted to know their stories, especially if they also held on to their Judaism. But I could only find evidence of their presence but never the traces of their own voices. Bishops could complain about their bad influence on the “good Christians” and the Inquisition could interrogate them about their illicit Passover rituals, but I wanted to hear their stories from their perspective. I wanted access to their intimate thoughts and moments of enlightenment and despair.

These multi-layered networks of kin stretched throughout the Americas. In the spaces where Judaism was forbidden, there were individuals and groups of passionate crypto-Jews like the Carvajals and others who kept their forbidden faith in secret. However, if we turn to the Dutch and English Colonies of the Caribbean, we can find the first places in the New World where Jews could openly and safely embrace their faith. First in the short-lived Dutch enclave of Recife in northern Brazil (1630) and then in places like Curaçao, Suriname, Barbados and Jamaica, Jews were afforded basic civil rights that ensured their right to freely practice Judaism. These colonial American Jews, however, belonged to the same converso networks as those who lived under the Inquisition. The Jews who built the synagogues and mikvaot (ritual baths) of Willemstead and Bridgetown were all descendants of Portuguese conversos and many of them maintained contact with their relatives who lived as Catholics in the Iberian world.

It was this network of colonial merchant congregations, whose members referred to themselves as the naçao—the nation–that created the basic infrastructure for Jewish life and belonging in the Americas. Until the American Civil war, these Caribbean communities were the center of the Jewish Americas. There were satellite Spanish and Portuguese congregations in New York, (founded in 1654 in what was then new Amsterdam), Newport, Philadelphia, Charleston and Savanah. Their synagogues had a shared architectural style, they used the same prayer books that were published in Amsterdam and London and maintained close contact with each other. Kosher meat would be shipped from one port to the other, cantors and teachers would move around these communities depending on the shifting needs and internal politics of each locale.

Even as the numbers of Ashkenazi Jews began to swell the ranks of these communities, their leadership vigorously preserved the Minhag, their particular style of Sephardic ritual and liturgical practices. As Reed College Profesor Laura Leibman has shown, these communities expressed their religiosity often in less textual ways than their Old World counterparts. Synagogue architecture, the building of luxurious ritual baths, lovingly crafted tombstones and the commitment to the laws of the sabbath and other ritual matters along with a distinctly Jewish notion of redemption set the Jews apart from their Christian neighbors and expressed their faith in the God of Israel.

An area where their religious tradition did not set them apart was slavery. Jews engaged in slaveholding in patterns not dissimilar to their neighbors and we have little evidence that their religion prodded much introspection about the barbarity of the institution. Scholars like Jonathan Schorsch, Stan Mirvis and Aviva Ben-Ur have shown the entanglement of Jews and free people of color in their struggle for civil rights in the Americas and how the question of race and whiteness defined much of the discussion of Jewish acceptance into the political system, in a similar way that it worked for freed people of color. So yes, the question of Jews and race in the Americas is complicated and while the Americas represented an unprecedented opportunity for Jewish political agency, that freedom was qualified and delimited by the reigning Christian (and white) hierarchy. Jewish freedom and success also came with the stain of living and thriving within slave societies.

In the wake of the Latin American wars of independence the Inquisition was dismantled and although Jews were not allowed official entry into the new republics of the Americas there was no longer the official persecution of the Inquisition. By the 1850’s Caribbean Jews begin establishing small merchant enclaves in Venezuela, Colombia and Panama. Quite quickly these Sephardim married into the local Catholic population and many of their children, bearing classic Sephardic names like Maduro, Del Valle and Cohen-Henríquez became some of the leading politicians of these young republics as they assimilated into the all too welcoming Caribbean society.

It is at the turn of the 20th century when a new wave of Sephardic immigrants arrived in Latin America and completely remade Latin American Jewish life. Fleeing the instability and economic depression in the Ottoman empire Ladino (Judeo-Spanish) speaking Jews from Turkey and Arabic speakers from Syria began to arrive in Mexico and the Caribbean. A smaller immigration of Moroccans came to work in Amazon during the Rubber boom. The Ladino speakers had the advantage of being able to communicate, more or less, with ease. Within a generation their Ladino would seamlessly be absorbed into their Spanish. The only remnant of Ladino would be in a few idiosyncratic words—especially for food and religious references— mazal, bumuelos, etc and of course, songs of love and longing.

Interior of the Monté Sinai congregation (Damascene Jews) in Polanco. Notice the Mexican and Israeli flags flanking the sacred space housing the Torah scrolls. The synagogue evokes the congregation’s middle eastern roots in the use of lattice work while maintaining a sleek modernist aesthetic reflecting the communities’ sense of belonging in their new home.

The Syrians arrived around the same time as Maronite Christians began streaming into the Americas from many of the same Ottoman or formerly Ottoman territories. The Syrian Jews often referred to themselves as árabes, to differentiate themselves from either the Turcos (Ladino speaking) or Yiddish speaking Polacos or Rusos, i.e. Eastern European Jews. Generally speaking, these groups established separate communities, sometimes even with separate schools and social clubs. In this way each group’s liturgical customs, religious sensibilities and social networks were preserved and at least in the first generations there was a high level of endogamy, Shamis (Jews from Damascus) would only marry other Shamis and Halabis (Jews from Allepo) would only marry Halabis, and marriage to an Ashkenazi Jew was highly irregular in larger communities like Mexico City. Syrian Jews form their own sort of diaspora within a diaspora with bonds of marriage and business connecting extended families from New York to São Paulo, Panama or Mexico City. In this sense they are quite similar to the colonial-era converso networks discussed earlier despite the fact that they have no connection to those Portuguese merchants living under the Inquisition.

The only connection that does exist is an almost mystical one. Contemporary Latin American Jews can turn to the past to find a way to mediate their many loves and multitudinous identities. By finding a Jewish presence in the colonial past they can lay claim equally to their Mexicanidad or their alma Cubana or any other varieties of amor de la patria alongside their Judaism and their fidelity to their Shami or Turco inner circle. Very quickly these Jews found a way to enjoy and engage these diverse elements. Embracing the countries that gave them refuge from persecution and poverty in the old world, they found their own sort of mestizaje as they embraced the old and the new and refashioned both into something unique, personal and still unfolding.

Often this alchemy of identities can most easily be appreciated in that most basic and glorious of human cultural achievements- food. One rainy night in Mexico City I went to a small kosher restaurant in Polanco, the slightly upscale urban neighborhood that was once the main heart of the Mexican Jewish community, most have moved on to the suburbs of Lomas. My waiter brought me my plate of taquitos and salsitas. Along with the salsa verde y roja, there was a small bowl of tehine and another of muhamara—-a spread made of ground walnuts and pomegranate molasses.

From a kosher falafel stand in the trendy Condesa neighborhood, the package proudly declares that it is Kosher (transliterated alo gringo) but the imagery it uses is stereotypically Arab which points to the Middle Eastern roots of most of Mexico City’s Jews.

The flavors all worked perfectly together, the fire of the chiles and the soothing bitterness of the tehine and the sweet-sour silkiness of the muhamara. The waiter, a gentleman with clear indigenous roots, came by and wanted to be sure I knew how good the tacos were with the tehine drizzled on top. In one moment, in one small taco, I was able to experience the layered, complex and surprising culture that is Latin American Judaism.

Ronnie Perelis has the honor and pleasure of teaching and researching about the Sephardim and the Jews of Latin America and much more at Yeshiva University in New York City. He is also the director of the Rabbi Arthur Schneier Program in International Affairs at YU where he runs the Diasporas Project which focuses on how distinct cultures and communities connect across borders. He lives in Teaneck, New Jersey with his wife and children and he can’t wait to return to exploring the world face to face.

Related Articles

Indigenous Peoples, Active Agents

Recently, the Amazon and its indigenous residents have become hot issues, metaphorically as well as climatically. News stories around the world have documented raging and relatively…

Beyond the Sociology Books

If you are not from Colombia and hoping to understand the South American nation of 50 million souls, you might tend to focus on “Colombia the terrible”—narcotics and decades of socio-political violence…

Exodus Testimonios

The audience at Iglesia Monte de Sion was ecstatic as believers lined up to share their testimonials. “God delivered us from Egypt and brought us to the Promised Land,” said José as he shared his testimonio with the small Latinx Pentecostal church in central California…