When Sammy Sosa, a sixteen-year-old shoeshine boy from San Pedro de Macorís, signed his first baseball contract in 1985, he took part of his $3,500 bonus and splurged—on a used bicycle. I’m not sure what sort of ride fellow Dominican Michael Ynoa bought when he signed with the Oakland A’s for $4.25 million in 2008, but it likely had more than two wheels.

Despite his modest bonus, Sammy did okay. At Sammy’s 38th birthday party in 2006, a line of statuesque Venezuelan and Dominican models greeted guests to his home in Casa de Campo. They walked through his residence, passing by fish tanks as big as SUVs, and emerged into a backyard along the water’s edge. The celebration comfortably hosted 500 guests, including Salma Hayek, Julio Iglesias, and Dominican President Leonel Fernández. Sosa could, by then, indulge whatever whims he fancied. His final multi-year contract with the Chicago Cubs had paid him about $18 million a season; endorsements brought even more. Horatio Alger could not have imagined a more unlikely tale.

But the difference between Sosa’s $3,500 bonus in 1985 and Ynoa’s $4.25 million deal in 2008 underscores how much the business of baseball in the Caribbean has changed. And Major League Baseball (MLB) doesn’t like that one bit. No longer able to sign bushels of Caribbean prospects for a few thousand dollars apiece in hopes that a couple of them will make it in the majors, MLB has launched a campaign to control costs.

Caribbean baseball has never mattered more to MLB’s brand and bottom line. After Jackie Robinson vaulted the color line in 1947, darker-skinned Latinos began following the pigeon-toed Brooklyn Dodger on to major league diamonds. The best cohort of talent in the game today, Latinos won half of the Silver Slugger Awards given to the top offensive player at each position in the American and National Leagues in 2010 and 2011 and routinely dominate All Star line-ups.

MLB needs them more than ever, especially because the black community has turned its back on the game. African Americans, who contributed more than 27 percent of all major leaguers in the late 1970s, now make up a little over eight percent. Despite what baseball once meant—during segregation when African Americans built their own baseball world (the Negro Leagues) or during the fight to integrate the majors—a victory that eased the way for Brown v. Board of Education—the game elicits little more than a collective shrug these days in most black neighborhoods.

Caribbean baseball, however, has become the cornerstone of MLB’s player procurement system, and factors increasingly into its marketing and profitability.

The recently negotiated collective bargaining agreement (CBA) between MLB and the Players Association addresses the industry’s angst over escalating player development costs. It does so by sacrificing the interests of the next generation of Latino ballplayers to the clubs’ bottom lines. The Players Association, meanwhile, conceded these cost-cutting measures—which do not affect them directly—in the agreement in order to preserve the current members’ own generous pay scale.

The new contract, by imposing a tax on any club that spends more than a total of $2.9 million for signees from the Caribbean basin next season, will lower player development expenses. The tax will be set high enough to discourage the multi-million dollar signing bonuses that have rewarded top prospects in recent years.

More ominously, the new CBA set up a player-management committee tasked with developing a proposal to bring Latin America into MLB’s annual player draft, which now includes only the United States, Canada, and Puerto Rico. That change would eliminate the best thing that a Latino prospect has going for himself—the opportunity to begin his professional career as a free agent and thus shop his services to the highest bidder. But if the committee decides to include the Caribbean in the draft, a boy would be able to negotiate only with the club that selects him. Signing bonuses would drop accordingly.

Though a few Latinos, mostly Cubans, played for major league ballclubs in the first half of the twentieth century, few men from the Caribbean basin could pass through MLB’s color line. Some played in their own countries during the winter and joined Negro League clubs in the United States each summer; others forsook the racial hazards of segregated baseball and spent their careers in the Caribbean circuit.

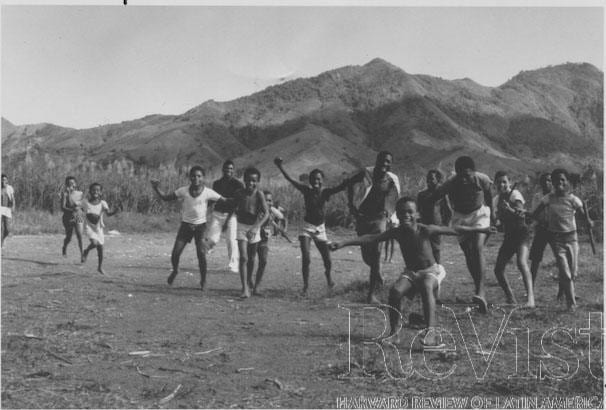

Baseball in the Caribbean was more simpático—a multi-racial and multi-national game since its origins in Cuba in the 1860s. And as Cubans—the apostles of baseball—spread the game around the basin, integrated play was adopted as an article of faith. Baseball was perceived, as Cuban independista Benjamin de Cespedes called it in 1899, “a rehearsal for democracy.”

Not so in the United States, where racial barriers stained the game during the 1890s when the nation abandoned the vestiges of progressive reconstruction. Given the other setbacks at the turn of the century—lynchings, Plessy v. Ferguson, sharecropping, and segregation—exclusion from major league baseball was hardly African-Americans’ most pressing concern. But there was a cost. Baseball had become an arena in which citizenship and U.S. identity were defined for generations of European immigrant boys. In that context, the exclusion of African Americans suggested that they were unworthy of attaining their birthright.

Darker-skinned people from the Caribbean basin were similarly dismissed in baseball until Jackie Robinson’s triumphant debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947 re-integrated MLB and allowed them in. Cuba’s Orestes Saturino ‘Minnie’ Minoso, Puerto Rico’s Roberto Walker Clemente, and the Dominican Republic’s Felipe Rojas Alou led the first wave of Latin talent. By the mid-1980s, when I started traveling to the Dominican Republic, Latinos comprised a tenth of all major leaguers. Half were Dominican.

Those mind-boggling numbers soon exploded. Latinos, not including Hispanic Americans born in the United States, make up over a quarter of all major leaguers today and well over forty percent of those in the minors. The Dominican Republic’s ten million people currently account for over a tenth of all major leaguers.

Now baseball is a multi-billion dollar business in the Dominican Republic and important elsewhere in the region. Its foundation is the Dominican Summer League—the entry league for most Latinos—which has more than a thousand players. It’s the largest professional baseball league in the sport’s history.

The Latin workforce in baseball ramped up considerably after major league organizations started building training academies in the Dominican Republic in the 1980s. Congressional limits on foreign minor leaguers in baseball had capped the number of available visas. Although major leaguers were exempt from the visa limit, many clubs had more Latin minor leaguers than they had visas to bring them to the States. The solution was to create Dominican academies where players could be trained and evaluated without visas. It was also much cheaper than bringing these players to the United States.

Epy Guerrero built the first academy in Villa Mella on the outskirts of Santo Domingo for the Toronto Blue Jays. A spare, utilitarian facility featuring two well-manicured ballfields, the complex cultivated a crop of future major league All-Stars. I got lost after visiting there in the 1980s and wound up driving through the nearby Santo Domingo dump where an army of scavengers, rags covering their mouths and noses, picked through refuse. Given the alternatives—working in the dying sugarcane industry or the growing tourist trade, much less living in the dump—it’s no wonder that the boys who trained at the academy took their sport seriously.

The Dodgers saw the talented cohort of ballplayers making their way from Villa Mella to Toronto and opened their own, state-of-the-art, academy, Campo Las Palmas, in 1987. This first-world facility caught baseball’s attention as the Dodgers began producing an even greater number of talented ballplayers than Toronto and did so at a minimal cost. In the years since, every major league organization has opened an academy where they house, feed, and train their youngest players. A boy usually gets two or three years there to prove he is worthy of being sent to the United States to play. He eats well, receives better medical attention than ever before, and plays ball. At more progressive academies, he will learn rudimentary English and perhaps make progress on his education while lifting weights and training the rest of the day.

Most of the academies are now clustered near Boca Chica and San Pedro, near the Santo Domingo airport, convenient for front office personnel who fly in for a few days to evaluate their employees’ progress. They are rarely forced to leave their comfort zone as they watch the players compete in the Dominican Summer League.

The fruits of these investments can be seen on major and minor league diamonds across North America. Over the last twenty years, Dominicans, and to a lesser extent, Venezuelans, have made a disproportionate mark on the game. Pedro Martinez, Vladimir Guerrero, Albert Pujols, Robinson Cano, José Reyes, and Alex Rodríguez could each end their careers by joining Juan Marichal, the only Dominican Hall of Famer, in Cooperstown. And Pedro, Manny, and Big Papi (David Ortíz) even brought the Boston Red Sox to baseball’s promised land, not once but twice.

Until recently, Latinos signed for far less money than boys in the United States. In 1990, major league clubs signed about 300 Dominican boys to contracts for a total of $750,000. Most received bonuses of between $2,000 and $5,000; not one of them received nearly as much as top prospects in the United States. By 2005, however, the average signing bonus for the 407 young players who signed that year had risen to about $33,000. And then, at least from MLB’s perspective, matters got out of hand.

In the first four months of 2011, the 188 boys signed by major league organizations received bonuses averaging almost $131,000. Multi-million dollar signing bonuses had become commonplace.By then, Latinos did not only better understand the system, they had figured out how to take advantage of it. MLB never intended it to be that way.

When MLB instituted its annual player draft in 1965, Latinos were left out of the process. Only boys in the United States who were of the age at which their high school class would graduate were eligible for the draft. As with the NFL and NBA drafts, once a player is selected, he can negotiate only with the organization that drafted him. Canadian and Puerto Rican youth were added to the draft later. But as long as signing bonuses for boys in the Dominican Republic, Venezuela, Nicaragua, and elsewhere in the Caribbean remained far below the U.S. market, major league scouts prospected for players at rock-bottom prices. Their largely unregulated, bargain basement approach soon produced the best wave of talent the game had ever seen.

This mother lode of young ballplayers, however, spurred the emergence of a lucrative market in juvenile talent that at its worst is little more than the trafficking of children. The boys, mostly from poor backgrounds, often equipped with little more than an eighth-grade education, and made vulnerable by their desire to become peloteros and take care of their families, nevertheless benefit from two MLB policies. The first is that because they are exempt from the draft, they begin their careers as free agents. That means they can sign with whatever club they chose, presumably the one that makes the most attractive offer.

A second policy is the “Jimy Kelly” rule. After the Toronto Blue Jays were chided for signing a 13-year-old Dominican boy, Jimy Kelly, in 1984, MLB passed a rule that prevents a club from signing a boy until the summer of the year he turns 17.

That prohibition spawned an industry of self-styled agents known as buscones (from the verb buscar—to search) who approach boys as young as 13 and offer assistance in developing their baseball talents. The boy often moves in with hisbuscón or to a facility he owns. There, the boy is fed, housed, and trained. When he approaches his seventeenth birthday, thebuscón attempts to create a market for his services by taking him to tryouts at the academies that each of the 30 MLB clubs operate year-round in the Dominican Republic. A smaller number of clubs maintain Venezuelan academies and all organizations scour the Caribbean basin for kids who often end up at a Dominican academy.

In return for his speculative investment in a boy, the buscón takes about thirty percent of his signing bonus and sometimes his salary, too. Buscones run the gamut from freelance operations housing boys in ramshackle accommodations to the multi-million dollar International Academy of Professional Baseball that former Yankees executives Steve Swindal and Abel Guerra set up with former U.S. Ambassador to the Dominican Republic Hans Hertell. Boys obviously prefer the living conditions and amenities at the better-heeled operations but most will take whatever they can get. Some buscones are honest and well-intentioned; others are thieves who abuse their charges in hopes of a pay-off when and if they sign professionally.

Some encourage their boys to take vitamins that turn out to be steroids (often veterinary steroids); others persuade them to lie about their age. When clubs gauge a boy’s potential, they reason that the younger he is, the higher his upside is likely to be. But clubs have been made the fool when the seventeen-year-old they sign turns out to be several years older. The Washington Nationals were a laughingstock when their $1.4 million, 17-year-old signee Esmailyn ‘Smiley’ González turned out to be neither seventeen nor Esmailyn González. He was 21-year-old Carlos Álvarez Lugo using the identification of a relative whose disabilities prevented him from venturing from his home in a small rural town. Those who knew of the deception were either bought off or gladly cooperated to benefit the families involved. Making matters worse, drug testing after boys sign has found a high incidence of the use of performance enhancing drugs (PEDS). Once boys stop juicing, their hard hit balls don’t travel so far and their sizzling fastballs slow down.

This wild West scene, replete with MLB employees and buscones caught skimming bonuses, age and identity fraud, and PED abuse, led MLB to send the sheriff to town in 2010. MLB dispatched long-time baseball executive Sandy Alderson to the Dominican Republic to clean up Dodge. Alderson spoke of instituting MLB-run youth leagues for Dominicans under the age of 17 to displace the buscones, as well as drug-testing and finger-printing prospects as young as age 15 to create a database to verify age and identity.

But Alderson encountered resistance from Dominicans both because of his imperial swagger and the realization that MLB was trying to cut the buscones out of the picture. He soon resigned his position and took on an even more daunting task—as the New York Mets general manager. But MLB is serious about regaining the upper hand in the Caribbean talent market. The new contract will cause signing bonuses to fall, and the prospect of extending the draft to the Caribbean is now on the table.

Caribbean baseball is at a crossroads. MLB has long profited from the region and wants to ensure that its escalating player development costs will drop in future seasons. An international draft would be a boon for Baseball Inc. but take millions off the table for boys in the region. MLB spokesmen have cast their efforts with a patina of reform—that they are a means of cleaning up the game.

But many in the region distrust MLB imposing a tax on signing bonuses as a self-serving solution and consider an international draft even more objectionable. Those who seek to speak for baseball and youth in the Caribbean must be bolder in challenging MLB and the Players Association on these matters. They need to take greater ownership of the game in their nations, protecting their young countrymen from MLB’s drive for profit and reducing their manipulation by buscones.

There are win-win reforms, especially ones that could better equip the overwhelming majority of signees who never reach the majors and find the best years of their lives over before they turn twenty-one. MLB could set aside some of its lucre to better prepare boys vocationally and academically. They could give something back to the region that defines the game today with its impassioned virtuosity. Baseball has become the pan-Caribbean pastime; it’s where the game has retained much of it dwindling soul. But that soul is endangered by the dynamics of baseball as business. It doesn’t have to be that way.