Challenges of Aging in Brazil

Getting Old Before Getting Rich

The elderly men without pensions or savings were trying to eke out a living selling water and juice in the streets of São Paulo. This recent image on Brazilian television drew attention to the precarious fate of the elderly. Shifting demographics create a challenge for all except the very rich. Among the middle class, everyday personal experience and conversations with colleagues in their 60’s and 70’s make clear that they are spending considerable amounts of time and money to visit and care for their elderly parents and mothers- and fathers-in-law. Great-grandparents and great-great-grandparents, rare in the past, are now becoming common. Only a minority is well-off. For the majority, getting old before getting rich is giving rise to unprecedented new challenges for families and communities, as well as government. The growing number of senior citizens can also have impacts on the economic growth and social welfare of Brazil.

While smaller families and longer lifespans are undoubtedly positive in many respects, thedemographic process of changing age structure has its downsides in countries in which poverty is widespread and welfare is limited. Brazil shares many of the challenges due to aging with other countries, but there are also many problems that are specific to Brazil. There are no easy solutions in sight.

In demographic terms, the age “pyramid” that used to have a wide base and narrow tip is becoming heavy at the top and narrow at the bottom. By 2050, all age brackets under 60 will be smaller than the older bracket. This transformation of age structure, almost turning the pyramid upside down, is due to both lower fertility and higher longevity.

The proportion of Brazilians over age 60 has risen from 5% in 1970 to 15% in 2018 and is projected to be above 25% in 2050. That is, by 2050, one out of every four Brazilians will be over 60. Fertility was nearly 6.0 children per woman in the 1970s, but fell to only 1.8 in 2018, below the replacement rate of 2.2. At the same time, average life expectancy at birth rose from 60 years in the 1970s to 76 years 2018. Population projections show that in the higher age brackets, there will be many more women than men. Income distribution in Brazil is notoriously unequal. Both fertility and mortality are higher among the lower-income brackets.

Because of lower fertility since the 1970s at all income levels, fewer sons and daughters are nowavailable to provide care for their aging parents, who often live into their 80’s and 90’s. Furthermore, younger generations have often moved to other locations in Brazil or abroad.Because of migration and mobility, many grown children living in other cities or states only see their parents on special occasions. Those left to provide support and care for their parents can be overloaded with responsibilities and costs.

The responsibilities and costs of raising one’s own children have also risen. Rather than contributing to production on family farms, as in the rural past, children now cost money for their schooling and their consumption. There are also many indirect costs. For example, because of growing concerns about security on the streets and in public transportation, many parents drive their children to school and then pick them up.

The fact that many elderly parents are widows or widowers or are now separated or divorcedmeans that they often require more care from their children or other caretakers, rather than relying on a spouse. Some relief may be provided by the middle-age men and women who go back to live with their elderly parents after their own separation or divorce, but this is more common among the generations in their 20s and 30s, whose parents are not yet over 60. The youngsters often have children of their own, i.e. grandchildren for their parents. There is also a gender difference. Although some women can live off their former husbands’ savings or pensions, they generally live longer than men and have lower income, savings and retirement pay.

The social security system in Brazil is already under strong pressure from the increase in the ratio of dependents to active workers who make monthly contributions. People are allowed to retire at young ages, even in their 50’s, if they started working young. The situation is made worse by high rates of unemployment, now at the highest levels ever, as well as underemployment anddiscouragement to seek any job at all. There are too many beneficiaries for too few contributors.Because of the high political cost, previous administrations have not been able to reform the social security system. The conservative administration that took office in January 2019 puts high priority on this reform, which will probably make retirement more difficult.

Better medical attention, involving more office visits, check-ups, treatments and medicines—sometimes including complex surgery—extends lifespans. However, many of these people are living longer without being healthy, especially those over age 70. The bodies of the elderly, especially of those who have lived through serious diseases or accidents, require more assistance, sometimes daily around the clock. Even so, their bodies often age better than theirbrains, which are increasingly vulnerable to diseases like Alzheimer’s and dementia, making themmentally unable to take care of themselves.

In spite of official government policy since the health reform of the 1980’s, Brazil’s state-run socialized medical system (Sistema Único de Saúde – SUS) is not able to provide sufficient health care to all citizens. There are long lines and few doctors and beds. Health care provided by official programs overloads government budgets, reducing investment and expenditures in other areas, like education, infrastructure and security. Private health plans are extremely expensive, especially for the elderly, and new plans can no longer be individual, but only for groups. They are difficult for most people to afford, making them even more expensive for the minority that pays.

The costs of private medical care, including doctors, hospitals and medicines, are very high and keep rising, while most retired people have fixed income. While labor is relatively cheap in Brazil, personal home care is expensive, especially now that it is subject to labor legislation and requirements to pay for 30-day vacations, a 13th month’s wage, social security, severance pay and other benefits. The official internet system called “e-social” is too complicated for most old folks to handle. Because of limitations on hours worked, weekends and holidays, some elderly people require three or more caretakers, who in turn require professional management. Many old folksstay living alone in their family homes. Rest homes, called asilos (asylums), are very costly and culturally not well accepted.

At the same time, on the positive side, although the elderly are the most unemployed, caring for the elderly means that there are new employment opportunities for younger people who are unemployed or who have less education or marketable skills. This provides some relief now thatmany unskilled jobs are being eliminated by technical progress in the form of machines, computers and robots, while only a few new jobs are being created.

In many cases, lifetime savings or property, assets that used to constitute inheritance for children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren and were intended as reserves for their education, arenow being spent on doctors, medicines and caretakers. That use of funds is a negative consequence for the younger generations.

Because the velocity of change in information technology leads to a generation gap, manyelderly people are not able to use digital equipment and social media that are increasingly required to deal with the banks, business and government bureaucracy or even to interact with family and friends. The fact that they need help with new technology means they may lose the respect of younger generations, who start playing with smartphones as soon as they learn to talk.

The disappointments about economic and political progress at the present time, which areconstantly hammered in by television and the media, discourage older people who experienced what they thought to be constant progress during the decades of the late 20th century and the beginning of the 21st century. Disillusion is not good for anyone in terms of health or resilience.

In urban areas, the elderly who increasingly live in apartments instead of houses with yards and gardens often feel lack of contact with nature: trees, flowers, fruit, water and scenery. The risks of theft and violence in the streets make them stay home more than they used to.

Some elderly women take up arts and crafts such as knitting, embroidery or painting, while elderly men may take up hobbies such as photography, woodworking or fishing. Increasingly, both men and women find company interacting with pets like dogs or cats, which also require care and therefore limit their mobility. There are few old folks’ communities or social activities for them to participate in activities with others of the same age.

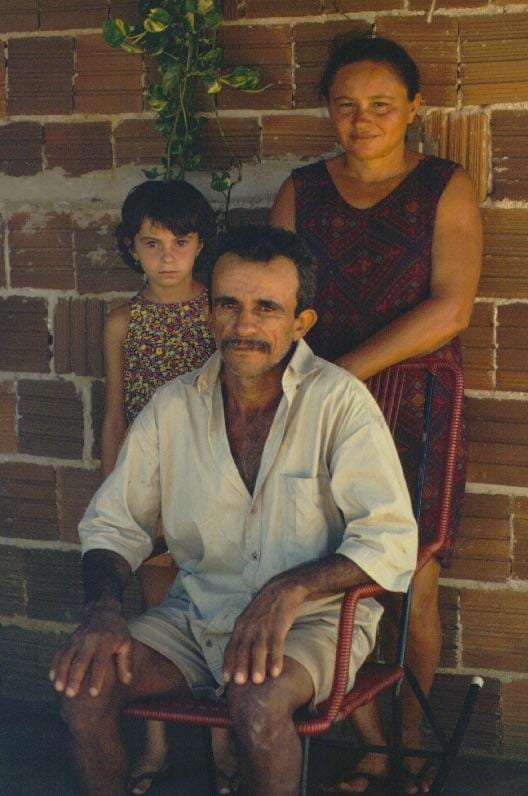

In rural areas, the elderly are often left to care for grandchildren whose parents have moved to cities. Although there are now many more cities and towns in the interior, the rural poor may beleft isolated on their empty farms or in small villages, especially when they do not have cars or motorcycles or cannot drive. There is practically no public transportation in rural areas.

Many of the elderly in the countryside can no longer perform physical farm labor on their own land or work for others. Nor can they afford to purchase labor-saving machinery like small tractors called tratoritos. Animal traction is now rare because it is slow and the horses and donkeys require constant care of their own. Lower physical capacity may make old folks feel useless, but at any rate it sets limits on their potential earnings.

What can be done to mitigate the negative effects of aging? There are various possibilities. There could be promotion of volunteer work both for and by the elderly free from the complications of labor legislation designed for male breadwinners. Their knowledge and experience could be made available to society through specific labor legislation that establishes appropriate rules for sporadic work as opposed to regular employment. They could take more care of each other.Community housing could provide collective oversight and attention without being fully institutional. While the elderly in Brazil already have legal rights to priority in lines in banks, stores and airports as well as some free transportation, there could be discounts for their health care and medicines. At the aggregate level, it would be important for more young people to get jobs, pay taxes and contribute to social security. In cultural terms, there could be more recognition of past achievements and current contributions of people born before 1950. There is no magic bullet, but there are many innovations that would go a long way to making better lives for all.

Now that many people are living more than 100 years, even in developing or emerging countries like Brazil, no one should bet on not being alive for decades after retirement. Nor should they count on family or government to take care of them as long as they live. This means that we all need to start to get ready for getting old during middle age or even before, whether we are rich or not.

Winter 2019, Volume XVIII, Number 2

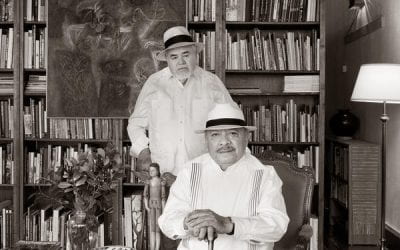

Donald Sawyer holds a Harvard A.B. 1969 in Social Relations and Ph.D. 1979 in Sociology. He is a former professor of Demography at the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG), and Sustainable Development, University of Brasília (UnB). He is a partner and founder of the Institute for Society, Population and Nature (ISPN), www.ispn.org.br.

Related Articles

Video Interview with Flavia Piovesan

Flavia Piovesan is a member of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, Professor of Law at the Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo and 2018 Lemann Visiting Scholar at the…

Aging: Editor’s Letter

There is no smell of pungent printers ink permeating my office. My interns—Sylvie, Isaac and Marc—are not scrambling to find FedEx boxes to send out ReVista issues to authors and photographers all over the world. I cannot feel the silken touch of the printed page…

A Story of Agricultural Change

Francisca Hernández García, 92, lives in San Miguel del Valle, a town of around 3,000 inhabitants in the Central Valleys of Oaxaca, an hour east of the capital city. She is one of the few remaining…