Children of Immigration

An Excerpt

Large-scale immigration is one of the most important social developments of our time. It is a transformational process affecting families and their children. Once immigrants are settled, they send for their loved ones or form new families. Hence, the story of today’s immigrants is also a saga of their children: a fascinating and critical but too often forgotten chapter of the immigrant experience. The children of immigrants, who make up 20 percent of all youth in the United States, are an integral part of the American fabric. This book explores their experiences.

First, a word about our use of the terms “immigrant children” and “children of immigrants.” When we refer to immigrant children, we strictly mean foreign-born children who have migrated, not the U.S.-born second generation. “Children of immigrants,” on the other hand, refers to both U.S.-born and foreign-born children. While the experiences of U.S.-born and foreign-born children differ in many respects (most importantly, all U.S.-born children are U.S. citizens), they nevertheless share an important common denominator: immigrant parents.

The children of immigrants follow many different pathways; they forge complex and multiply determined identities that resist easy generalization. Some do extremely well in their new country. Indeed, research suggests that immigrant children are healthier, work harder in school, and have more positive social attitudes than their nonimmigrant peers. Every year, the children of immigrants are overrepresented in the rosters of valedictorians and receive more of their share of prestigious science awards. They are regularly admitted to our most competitive elite universities. Immigrant children in general arrive with high aspirations and extremely positive attitudes toward education.

While we name and celebrate the hard-earned successes of many children of immigrants, there are reasons to worry about the long-term adaptations of others. Why should we worry? Because many children of immigrants today are enrolling in violent and overcrowded inner-city schools where they face overwhelmed teachers, hypersegregation by race and class, limited and outdated resources, and otherwise decaying infrastructures. Disconcertingly high numbers of these children are leaving schools with few skills that would ensure success in today’s unforgiving global economy. At a time when the U.S. economy is generating no meaningful jobs for high school dropouts, many children of immigrants are dropping out of school. In brief, while many immigrant children succeed, others struggle to survive.

Anxiety has surged in recent years over the continued large-scale immigration into the United States. As in eras past, immigrants have been received with ambivalence. Though immigrant children arrive with remarkably positive social attitudes toward schooling, authority figures, and the future we argue in this book that their developing psyches are susceptible to the negative “social mirroring” that many experience in the new land. We contend that the immigrants’ original positive attitudes are a remarkable resource that must be cultivated. As a society we would be best served by harnessing those energies.

With more than 130 million migrants worldwide and a total foreign-born population of nearly 30 million people in the United States alone, immigration is rapidly transforming the postindustrial scene. In New York City schools, 48 percent of all students come from immigrant-headed households speaking more than one hundred different languages. In California, nearly 1.5 million children are classified as Limited English Proficient (LEP). This is not only an urban or southwestern phenomenon schools across the country are encountering growing numbers of children from immigrant families. Even in places like Dodge City, Kansas, more than 30 percent of the children enrolled in public schools are the children of immigrants. To quote Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz, we are not in Kansas any more.

Discussions around immigration have typically concentrated on policy issues and, especially, the economy. With the exception of bilingual education, the debate about immigration as well as much of the basic research has focused predominantly on immigrant adults. Yet nationwide, first and second generation immigrant children are the most rapidly growing segment of the U.S. child population. The future character of American society and economy will be intimately related to the adaptations of the children of today’s immigrants, even in the unlikely case of a drastic reduction of immigration in the coming decades.

A central theme of Children of Immigration is how the children of immigrants are faring in American society. What do we know about the children of immigrants? How does immigration affect the family system? How are the children adapting to our schools and making the transition to the workplace? We focus attention on their schooling because schools are where immigrant children first come into systematic contact with the new culture. Furthermore, adaptation to school is a significant predictor of a child’s future well-being and contributions to society.

For the children of immigrants today, it is the best of times and the worst of times. In this book we explore the question of how it happens that while most immigrants enter the country with optimism and an energetic work ethic, many of their children are at risk of being marginalized and “locked out” of opportunities for a better tomorrow. Why will many immigrant children graduate from Ivy League colleges while others will end up in federal penitentiaries? For too many of the children of our most recent immigrants, the “Golden Door” of Emma Lazarus’s classic poem is turning out to be more gilded than gold.

Spring/Summer 2001

Reprinted by permission of the publishers from Children of Immigration by Carla Suárez-Orozco and Marcelo Suárez-Orozco, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, Copyright @ 2001 by the President and Fellows of Harvard University,

Related Articles

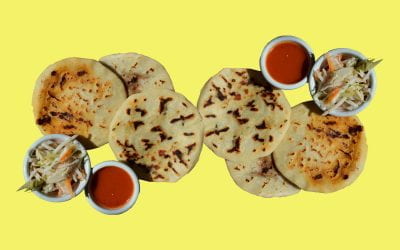

Salvadoran Pupusas

There are different brands of tortilla flour to make the dough. MASECA, which can be found in most large supermarkets in the international section, is one of them but there are others. Follow…

Salpicón Nicaragüense

Nicaraguan salpicón is one of the defining dishes of present-day Nicaraguan cuisine and yet it is unlike anything else that goes by the name of salpicón. Rather, it is an entire menu revolving…

The Lonely Griller

As “a visitor whose days were numbered” in Buenos Aires, Argentina, he tossed aside dietary restrictions to experience the enormous variety of meat dishes, cuts of meat he hadn’t seen…