Chile’s National Stadium

As Monument, as Memorial

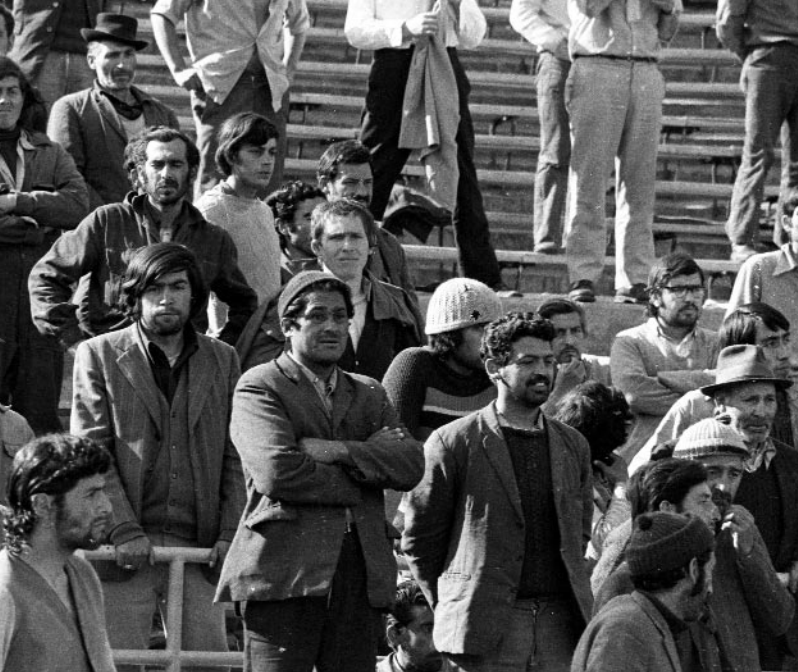

Prisoners in the National Stadium. Photo by Marcelo Montecino.

“If, in the earlier twentieth century, modern societies tried to define their modernity and to secure their cohesiveness by way of imagining the future, it now seems that the major required task of any society today is to take responsibility for its past.”

—Andreas Huyssen,

Present Pasts: Urban Palimpsests and the Politics of Memory

Stanford University Press, 2003, p. 94.

Chile’s national stadium became a national monument on August 21, 2003. Thirty years ago, just after the Pinochet coup, the National Stadium possessed the largest single prison population in the country. Today, the stadium joins other civil-society-initiated quests to commemorate Chile’s painful past.

“You mean they actually use that place as a sports stadium today?” an American friend asked me incredulously. I was telling her about a piece I was researching for a book on the case of Chilean friend and colleague Felipe Aguero, a professor of political science at the University of Miami. In 1973, Aguero had been held and savagely tortured in the National Stadium. Three years ago, Aguero’s case made international headlines when he “outed” his former torturer Emilio Meneses, now a retired air force officer who had also become a political science professor. Meneses teaches at Santiago’s Catholic University.

For my American friend Jeanette, as for many around the world, Chile’s National Stadium evokes images of frightened, haggard young men like Aguero in the stadium’s stands, with soldiers monitoring their movements. For Jeanette, who is not particularly political, images of the National Stadium have been seared and frozen into her memory from Costa Gavras’s 1982 film Missing. The film is about the search for the American Charles Horman and the duplicity of the U.S. government in its active desire for a military overthrow of the Allende government. Horman was held in the National Stadium before his murder by the military regime, and Costa Gavras’s film conveys the brutality of what was taking place in the stadium’s stands, rooms, and tunnels.

In the immediate aftermath of World War II, the stadium was used as a temporary clearinghouse for European refugees and immigrants. International athletes and musicians perform on the stadium field. Yet during the comparatively brief but horrific moments from September to November 1973, the military internationalized the National Stadium in an unprecedented fashion. Among the many thousands who were held prisoner in the National Stadium in 1973, several hundred were foreigners from countries around the world.

On September 22, 1973, in a rather bizarre move to assure both Chileans and the international community that all was well in the Stadium, the junta opened the Stadium’s doors to national and international media for an official “tour” of the conditions there. As Chilean photographer and journalist Marcelo Montecino and others describe, the military’s gesture backfired, as reporters and photographers observed first-hand soldiers’ cruel treatment of the detainees, as well as the poor state of those held there. Dramatic black-and-white photographs and footage of the prisoners in the stands made their ways into the international media. These images have remained etched in the memories of citizens across the globe.

Moreover, recently declassified U.S. government documents reveal that the CIA closely followed what was taking place in the Stadium. The agency proved discerning in its assessment of the Chilean military’s account of both the number of prisoners and the behavior of the interrogators. One document also reveals that in their efforts to “manage” the stadium’s burgeoning number of prisoners, Chilean general Nicanor Díaz and Brigadier General Francisco Herrera specifically approached a U.S. government agent to seek assistance, including a technical advisor that “must have knowledge in the establishment and operation of a detention center.” The advisor would assist in surveying for a new detention site. The generals also “requested the possible loan of inflatable tentage or other portable structures and equipment for temporary housing until the detainees can construct their own housing and administrative buildings.” U.S. Ambassador Nathaniel Davis, who prepared the cable regarding the request, noted that while it might be ill-advised to provide an advisor for such an endeavor, the provision of tents and blankets might earn the U.S. some credibility with the United Nations Human Rights Commission, who communicated to him that the prisoners needed blankets.

Last year’s approval of the stadium as monument came none too soon. Since the 1990 transition from military rule, groups representing victims of human rights violations have fought strenuously to seek official support for arenas that publicly expose the atrocities of the past, that materially represent the many violations of the authoritarian regime. The Stadium as monument will become an official “realm of memory” within a new political, legal and cultural milieu. This new environment has only recently begun to acknowledge the need to address more systematically the significance and consequences of state-sponsored torture as well as statesponsored death and disappearance.

Entitled “Open Museum, Site of Memory and Homage,” the monument proposal contemplates an array of symbolic commemorations, both within the Stadium’s walls and beyond its gates. Using audio and videotapes, murals, paintings, plaques, and sculpture, conceptualizers of the monument have developed a plan that travels through several areas of the Stadium. In addition, artists will create works that consciously relate what occurred in the Stadium to global human rights representations.

Their work will reflect the startling horror of executions and torture taking place between September and November 1973, that the International Red Cross estimates reached “some 7,000 prisoners on September 22.” Between 12,000 and 20,000 Chileans and foreigners were detained in the Stadium for periods ranging from two days to two months. The Stadium was no mere holding tank. In a somewhat sterilized, matter-of-fact account of the conditions and treatment in the Stadium, the Chilean government’s Report of the National Commission on Truth and Reconciliation includes the following:

There is information on the practice of torture and abuse of prisoners in the National Stadium. For example, the room for medical treatment was sometimes used for this purpose. Firing squads were simulated and other cruel techniques were employed. As a rule the prisoners were subjected to constant and intense interrogation.

…’The representatives and medical representatives of the IRCC (International Red Cross Committee) have found that many prisoners show signs they have undergone psychological and physical torture.’ This Commission also concluded that a number of executions took place inside the National Stadium, and that in a number of instances persons imprisoned there were taken out and killed. Such was the case of Charles Horman and Frank Terrugi, both United States citizens.

According to the truth commission report, at least 41 people lost their lives in the Stadium. Human rights groups believe the figure to be well in the hundreds, given the number of those who were detained in the Stadium, tortured and killed and then dumped in Santiago streets, ditches, and the Mapocho River during those early months of the regime. The imprints (including those etched into the Stadium’s walls by former prisoners) and the ghosts of those who were executed in the Stadium continue to haunt Chile. The many citizens who were tortured and survived their Stadium experiences find the 1991 truth commission report a sorely inadequate representation. It would take a decade for the Chilean democratic regime to return to the meanings of state-sponsored violence in the Stadium for policies related to truth-telling, compensation, and retroactive justice.

Human rights groups have established that there were more than eighty detention centers in Santiago alone. These clandestine jails used spaces ranging from schools and public buildings, like the Stadium, to private, secret homes and clubs. One of the most notorious of these secret centers was Villa Grimaldi, a place in which more than 5,000 Chileans were held and an estimated 240 people lost their lives. During the first half of the 1990s, several organizations mobilized to reconstruct Villa Grimaldi as a memorial site. Now known as Villa Grimaldi Peace Park, the site was conceived by Chilean architect Luis Santibánez to “develop a park of reencounter, with a symbolism that remembers what happened in that place and to pay homage, through the plants and greenery, to the triumph of life.” Nevertheless, while the Villa Grimaldi Park is a symbolically important place of memory, it is physically remote. The serene while slightly disturbing quality and feel of Villa Grimaldi remain hidden, masked behind high walls topped with barbed wire. Given the polity and much of society’s reluctance to confront the painful elements of Chile’s past, Villa Grimaldi is visited infrequently as a memory site.

The National Stadium, on the other hand, is clearly a cultural icon of the nation. As a site of traumatic memory, the Stadium thus poses unique opportunities as well as challenges. With its 80,000-seat capacity, the Stadium is the site of the most important soccer matches in the country (and a World Cup site in 1962), immensely popular musical concerts, and other athletic and cultural events. It is extremely “inhabited.” Tens of thousands constantly come and go through the stadium’s gates. The fate of the Stadium as monument does not risk the physical, social and cultural relegation common to many conventional historic monuments.

Nor will the monument assume the quality of some static, impenetrable granite object commemorating fallen heroes. Too often, writes Chilean cultural scholar and critic Nelly Richard, a monument represents “the nostalgic contemplation of the heroic; the reification of the past in a commemorative block that petrifies the memorial as inert material.” In the stadium, citizens will travel in and through the monument, making relegation, distance, and inertia far more difficult. Locating the accounts of victims and their families within the monument necessarily engages the representations of the past atrocities with the vibrant, emotional lived experiences of the present.

Yet articulating this engagement among the pain inflicted on the former prisoners, the anxieties experienced by the prisoners’ loved ones, and stadium-goers constitutes a complicated enterprise. Professor of English and essayist Elaine Scarry has claimed that societies have yet to develop, or have yet even to possess the will to develop or articulate language that can really convey, in sentient terms, the intense pain of the tortured. Moreover, as Argentine sociologist Elizabeth Jelin writes, memorials are at inter-play with those who “possess” them in some way, those who often claim “ownership” based on memories of their own tactile, traumatic experiences in the memorials’ representations or spaces. Finding points of encounter that allow individual and collective, victim and viewer “working through” thus becomes a central challenge. Representations must strive for empathy, a relation among human beings that may, in fact, question the distance between those who were held and those who could have been held.

In Chilean filmmaker Carmen Luz Parot’s elegant documentary on the Stadium (2001), former prisoners share their accounts of coping and resistance strategies as well as their experiences of torture and despair. They describe inventing and organizing games, and even a choir; celebrating mass with a prisoner priest; communicating with their families through conscripted soldiers from the provinces in need of a lunch in Santiago on their days off. Through the documentary, the viewer observes the high degree of organization and innovation the prisoners achieved in the midst of a great deal of pain and disbelief (“How can this be happening? Why am I here?”). Journalist and former prisoner Fernando Villagrán describes that in his fits of hunger he discovered how tasty an orange rind could be.

Parot’s documentary visually accomplishes a rendering that one might characterize as very “Chilean”—the depictions of pain and grief are muted, shots of the Stadium today are soft rather than sharp. Unlike documentaries on torture in which the filmmaker re-creates graphic depictions of tortuous acts, Parot chooses to rely on the former prisoners’ accounts. For example, Felipe Aguero’s testimony of being tortured in the genitalia conveys a horror embedded in a discourse that is quietly, discreetly expressed and communicated. Parot avoids visual representations of “literal memory,” which may fold victims into themselves, as viewers shun the representations.

Inside, the Stadium-as-monument will preserve, commemorate, educate, and project. The project will recover fragments and remnants of the presence of the prisoners, including “a tour through the property and emblematic sites.” The dressing rooms of the Olympic pool will be recognized, for example, as spaces where the female political prisoners were held. The running track will be signaled as the primary torture site. Inside a “Memory Park” will “harbor sculpture generated from public competitions.” Outside are plans to recognize the prisoners’ families desperately seeking their release and any information on their relatives’ conditions and needs.

In a personalized account, Chilean writer Ariel Dorfman claimed that a 1990 public act, in which newly elected president Patricio Aylwin addressed tens of thousands of Chileans in the Stadium, recognizing the atrocities that had taken place there, and in which wives of the disappeared danced the “cueca sola,” “exorcised” the Stadium for him. Dorfman wrote that he now felt free to enter the Stadium, which until then he had vowed never to re-enter. Yet within this inter-subjective space of relating to the Stadium as a site of horrific memory, the notion of “exorcising,” of “closing the chapter,” may not capture what many victims of that space may have had to do or may continue to do to survive with their memories and their scars.

Rather than exorcising their traumatic experiences, survivors must often find ways of integrating these experiences into their identities, often fitfully accomplished through the process of recounting. And here is one of the essential dimensions of the Stadium as national monument: public recognition of the need for an environment in which to facilitate or contribute to this process.

Like the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington DC, the challenge to conceptualize the National Stadium as a memorial involves striking some kind of balance between the nation’s shame and an honoring of the dead and wounded. Memorials that testify to the state’s violence against its citizens, such as Argentina’s El Olimpo, or the U.S.’s Kent State, stand in stark, inescapable contrast to official monuments of glorious pasts. Such memorials become contested terrain between a state, anxious to convey unity in the face of past polarization and state repression, and a society in which no one account of the past is universally shared.

At the outset of the democratic transition, Aylwin established an official “truth” that he had hoped would contribute to reconciliation (thus, the name of the truth commission) and to “turn the page.” The truth commission report was eloquently written. It recommended that symbolic monuments be erected. Yet the report focused on the dead and disappeared and not those who were imprisoned and tortured and managed to survive. Moreover, the state did not actively promote, disseminate or encourage public discussion of the report. Its arrival and fading from public light mirrored the ways in which the state has tended to repress painful memories.

Today, the Lagos administration’s act of approving the Stadium as an historic monument can be interpreted in several ways. After an elite silence regarding the past throughout most of the transition from military rule, politicians seem to recognize that past trauma must be integrated into a national identity. The nation should neither deny nor repress the trauma. The administration’s approval of the Stadium-as-monument might thus be interpreted as an instrumentalist act. Chilean politicians across the spectrum have come to accept the inevitability of the unearthing of a traumatic past, and it might be politically strategic to take the offensive when it comes to symbolic representations of the past.

Yet socialist president Ricardo Lagos and his fellow socialist cabinet members and elected representatives have a complicated relationship to the past, including their relationship to Salvador Allende and his agenda for revolutionary change. On the one hand, resurrecting the memories of wounded and fallen comrades is a reminder of failure at a time when socialists as governing leaders strive to convey success, unity, and authority. On the other hand, within the left, resurrections of men and women who dedicated their lives to radical visions of change are also symbolic contrasts with today’s comparatively moderate progressive program, one which some on the left would charge as hardly a left program at all. Resuscitating memories of the past thus raises troubling questions for the present and future in terms of the nature of current political alliances and projects for a better tomorrow.

As Chileans construct the National Stadium as a place of memory, perhaps another dimension should also be contemplated, and that is the array of relationships members of the international community possess with the stadium. For years, I showed the Costa Gavras film to my Vassar undergraduate Latin American politics class. I always prefaced the showing with, “Keep in mind that Costa Gavras exercises poetic license in his depiction of what took place in Chile in September 1973.” Yet recently declassified U.S. government documents on Chile and the Charles Horman case reveal that Costa Gavras’ account is pretty on-the-mark.

Around the world, monuments themselves have become battlegrounds, as artists, designers, states and societies negotiate how to convey, or evoke, or even shock, passersby into contemplation and reaction. Monument conceptualizers have come to appreciate the unknowable dimension of just how deeply a monument will be perceived and by whom, as well as how perceptions of the monument will change over time, in distinct political-historical moments. The National Stadium as monument arrives amidst these debates, an iconographic structure whose insertion in the body politic will undoubtedly be a major force in the ongoing and by no means temporally linear process of coming to terms with the past a la chilena.

Spring 2004, Volume III, Number 3

Katherine Hite is an assistant professor of political science at Vassar College and the author of When the Romance Ended: Leaders of the Chilean Left, 1968-1998 (Columbia University Press, 2000) and coeditor with Paola Cesarini of Authoritarian Legacies and Democracy in Latin America and Southern Europe (University of Notre Dame Press, 2004).

Related Articles

Poverty or Potential?

Teresa stops me three blocks from Nueva Imperial’s main plaza on a quiet Wednesday morning, eager to chat. She is wearing a light blue sweater and a matching blue headband glowing slightly against her dark black hair.

Editor’s Letter: Chile

I was hesitant to do an issue on Chile when I had other topics broader and richer in content. Although in a way Chile seems like an obvious choice because of the DRCLAS Regional office there, I felt there were other priorities in terms of substance.

Three Students, Three Experiences

I was extremely impressed with how successful the Chilean health system has been in improving the health of its citizens despite its limited resources. Its success, however, in many…