Christianity between Religious Transformations

Impact on Latin American Politics

In the second half of the 20th century, Latin America was surprised by religious changes that not only were transforming the religious panorama, but also influencing both society and politics.

Beginning in the 1950’s, some in the Catholic Church—not just priests and other religious, but workers, peasants and students—began to be concerned about returning to the system of Christendom established between the welfare state and the Church in Latin America. In other words, in a Christendom system, the state provided the material resources, and the Church took charge of social works like education, healthcare and providing assistance to the needy, matters that usually would be responsibility of the state, and that at the same time, this religious support was the source of its legitimacy. The Christendom system certainly was not the model proposed by the primitive Christian communities.

Gradually those that were upset by the system of Christendom sought a return to origins, in other words to the Bible and the first Christian communities to find a new way to live Christianity in the context of Latin America’s reality—violence, poverty and inequality— at the end of the 20th century. Some dioceses, groups of priests and lay members began to implement pastoral changes that were able to provide a more coherent response of the Christian message to the Latin American reality. But, above all, youth groups of workers, students and peasants formed small grass-root communities that analyzed the current reality and, based on the Bible and social doctrine, fostered new views and ways to face the Church’s mission.

For example, in Brazil, at a conference of the Catholic University Youth (JUC, after its acronym in Spanish) in 1960,) the student board presented a paper that by SEEING the socioeconomic and political reality, they also saw the need for a social change given the huge social and political injustices. Therefore, they decided to ACT by committing themselves to change that reality. These changes implied an agrarian reform, fighting capitalist monopolies, national freedom from international interference, and a reform of the educational system. They based their stance on Christian authors that the movement had been working on from Thomas Aquinas to the French philosophers Jacques Maritain and Emmanuel Mounier, and right up to several social papal letters from the 20th century. Their conclusions were original and went beyond the Church’s traditional view of social doctrine or the points defended by Christian Democracy. The document took many Brazilian conservative bishops by surprise as they witnessed the growth of this youth movement, becoming alarmed by the possible Marxist infiltration or by the use of a Marxist vocabulary inside the Church itself.

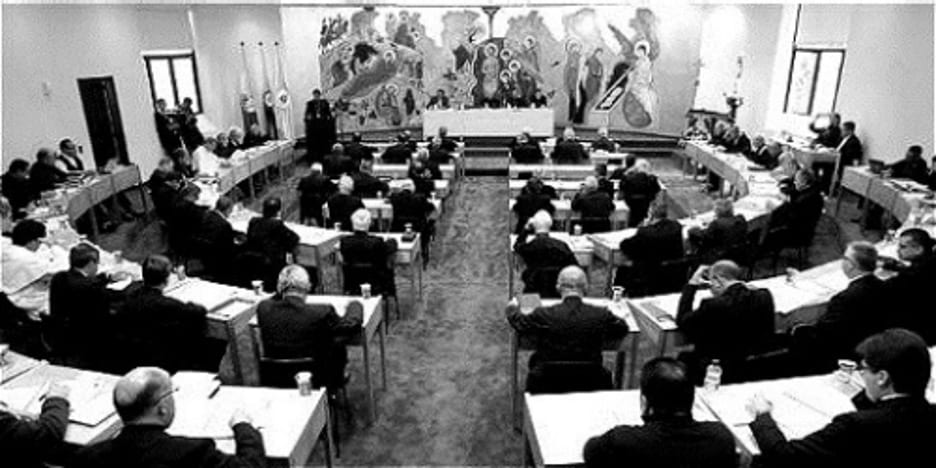

Second Meeting of the Conferencia Episcopal Latinoamericana // Reunión de la Segunda Conferencia Episcopal Latinoamericana, Seminario Mayor de Medellín, de 1968

Nonetheless, official Church meetings like the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965) and continental meetings like those of Latin-American bishops in Medellin (1968) and Puebla (1979), gave their support to these kind of movements in the Church. Believers of any social and racial status were able to form small grassroot communities in all the parishes. As a result, many of them began to experience Christianity in a practical and powerful way, and they committed themselves to change the social injustices that affected the poorest people.

Exactly 50 years ago, Gustavo Gutierrez published Liberation Theology in Lima, inspired by his pastoral work accompanying the grassroot communities in his parish, a poor neighborhood of Lima, but also by the spiritual path taken by students and professionals whom he advised in Peru and elsewhere in Latin America. However, his experience was not unique. In the 60s and 70s, authors like Juan Luis Segundo in Uruguay, Lucio Gera and Jose Miguez Bonino in Argentina, Leonardo Boff, e Ivone Guevara, Ruben Alves in Brazil, Jon Sobrino and Elsa Tamez in Central America, among many others, published theological works with a similar perspective and a lot of people were talking about liberation theology.

Nowadays, many people say that liberation theology is dead. But no, it isn’t dead. Ideas cannot be killed. However, many of the Christian lay people and pastors that were its inspirers and followers were indeed killed—just as at the beginning the elites tried to kill Christianity and for centuries killed Christians accusing them of crimes they didn’t committed. The same has happened with the ecclesiastic movement associated with liberation theology.

Theology is an intellectual effort concerning the way humans can live the experience of God. Pastoral theology, similarly to liberation theology, it’s about all a reflection, in other words systematization, of the experience, of the way to live Christianity. In this case, the way of living it in the second half of the Twentieth Century in Latin-America. But also in other countries, because liberation theology it’s a product of universal Christian history and not only Catholic. Therefore, in other Christian churches like the Presbyterian, Lutheran or the Methodist, there was an ecclesiastic transformation and a theological production along the lines of liberation theology.

Pope Paul VI received by President Carlos Lleras Restrepo // Papa Paulo VI recibido por el Presidente Carlos Lleras Restrepo, en Bogotá, agosto 1968

Traditionally, theology based its tenets on several philosophical concepts in the 60’s in which these Christian groups and the theologians in particular talked about the social reality and the sciences that help us to understand it. For example, the Economic Commission for Latin America (ECLAC) studied, the theory of dependency; Argentine-Mexican philosopher Enrique Dussel examined the history of Latin-America Church from the perspective of poor people. These ideas from the social scientists, of course, became the first outlines of what we today know as the theory of decolonization used by the communities and theologians to conduct the first theological elaborations denominated as liberation theology and a Latin American theology conducted by women. Occasionally, they used Marxist concepts to outline and explain social reality. Latin American theological efforts, although they do not invalidate the dialogue with philosophy, also dialogue with other human and social sciences. Therefore, this interdisciplinary perspective gives a framework to theologians of both sexes to understand and make explicit the experience of God among the impoverished communities of Latin America.

Let’s look back to explain that liberation theology was not completely apart from the Church as a whole, but to examine why it was persecuted, why some said that it was dead, but that nevertheless (and why) it remains alive and relevant. In 1891, Leon XIII’s papal encyclical Rerum Novarum, (New Realities) resumed the Christian demand of analyzing the surrounding social situation and to care for those that suffer and live in vulnerable circumstances. As a result, in the 20th century through many other social papal encyclicals, several Popes went in depth in this perspective that gave origin not only to the Church’s social doctrine but also to a pastoral that accompanied the great social challenges of the century. One of them was the social situation and the growing secularization of the working class that was increasingly influenced by anarchism, socialism and communism.

To deal with a challenge of such importance, shortly before World War I, Joseph Cardijn, a priest from a working-class parish in the outskirts of Brussels, Belgium, developed a new pastoral that proposed that workers should be in charge of their own evangelization by creating grassroots communities in their workplaces. Later on, the pastoral concept spread through Europe, the United States, and in the 30s and 40s arrived in Latin America. The adherents to the movement tried to see, understand and specify their daily problems, among which was the need to fight for their own interests within an unjust economic system that did not provide any kind of social protection. At the same time the question arose: How would have Jesus reacted to this situation? If it’s unjust, it is a sinful situation! What does the evangelical message tell us? How to face this sinful situation?

This is how to SEE, to JUDGE and to ACT came to be. This new pastoral practiced by workers and youth in particular, spread to other social groups such as students, professionals, peasants— both men and women. The change from stark spiritualism to a proactive spirituality gave rise not only to new organizations inside the Church but to important social Christian movements, that in a beginning supported Christian Democracy since it was also inspired in the Church’s social doctrine. But, as we already mentioned, many Christians started to question the model of Christendom in which Christian Democracy was framed, and also its inability to formulate deeper and speedier social changes. Therefore, in the 60s after breaking with Christian Democracy, more radical students, workers and peasants’ movements of Christian inspiration arose, such as like Acción Popular in Brazil, MAPU (Movimiento de Acción Popular Unitaria) in Chile and Uruguay and many others. Some of these made up political alliances in the 70s with Marxist groups to create more extensive political fronts like Unidad Popular in Chile or Frente Amplio in Uruguay or el Partido de los Trabajadores in Brazil in the 80s.

Some of the bishops, in most of Latin American countries, looked toward the framework of sociology to try to SEE, to understand in greater depth not only the social situation in which they had to act, but also the necessary reorganization of the diocese itself. Through the pastoral ministry, they looked for a way to integrate the work of diocesan priests, religious orders and congregations and secular movements. This way they paved the path for synodality, in other words to walk together as People of God, (all Christians in equality) concepts that were developed by the Second Ecumenical Vatican Council.

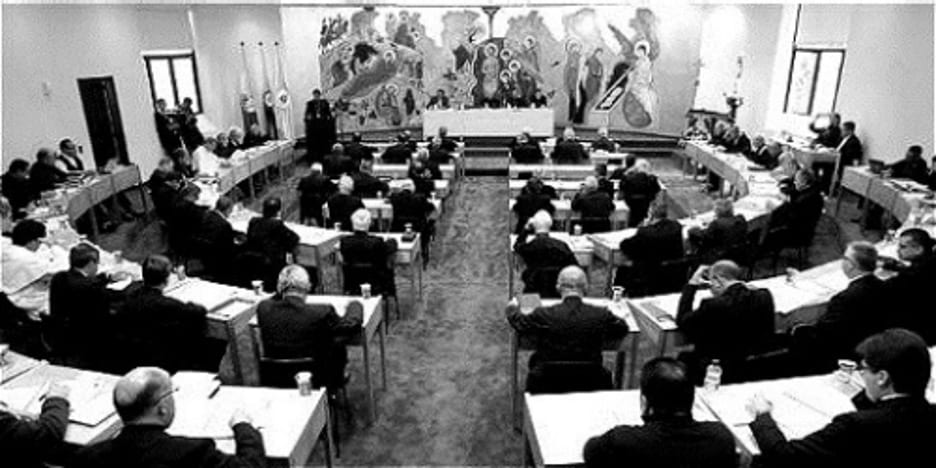

Third Congreso Continental de Teología organized by Amerindia at the UCA // III Congreso Continental de Teología organizado por Amerindia en la UCA San Salvador, en Agosto, 2018

A Council is the meeting or assembly of bishops from around the world; therefore, the word ecumenical means universal, to treat matters that define the path of the Church. In addition to the bishops, the Second Ecumenical Vatican Council counted on the participation of theologians as advisors, as well as representatives from religious orders, secular organizations and people from other religions and Christian denominations. They were invited by Pope John XXIII as observers. At the initiative of Belgian Cardinal Joseph Suenens, the Council invited 21 religious and secular women as observers. The Council was convened by Pope John XXIII in 1959 to establish a bigger dialogue with the modern world and to give an updated answer from the Church’s perspective and for the future in an ever changing world. The Council participants addressed an internal renovation of the Church. John XXIII spoke from the beginning about the need to pay attention to the “Signs of the Times,” among which he emphasized the situation of the poor, the workers, the so-called Third World Countries and the situation of the women. The Council took place between 1962 and 1965 and due to John XXIII’s death in 1963, it was concluded by Paul VI. Four important constitutions were published, including one that makes reference to the Church in the world Gaudiun et Spes (Joy and Hope). Likewise, among the nine decrees: The Church’s missionary activity, the activity of the secular ministry, the renewal of the religious life, the relationship with other Christian denominations and three statements concerning religious freedom, Christian education and Catholics’ relationship with other non-Christian religions. All of them were much talked about throughout Latin America.

The assembly of Latin-American bishops that took place in Medellin in 1968 took care of adapting the Council’s proposes to the Latin American context. The bishops spoke clearly about the Latin American situation, which they described in one of their documents as being a situation of institutionalized violence and recognized it as the reason why the Latin American population lived in poverty. They proposed all the diocese should follow the new pastoral guidelines making the parishes responsible for organizing the ecclesiastical grassroot groups using the See, Judge and Act methodology.

That’s why many organizations and social movements of Christian inspiration started fighting for fair salaries and basic services like electricity, drinking water, public transportation in the cities, and for land and water in the rural areas. On many occasions, they competed against Marxist political parties and revolutionaries, while at other times, these groups of Christian inspiration forged alliances with them to achieve objectives that they considered to be just.

The forceful messages from religious leaders and the accompanying social mobilizations were not well received by political groups used to the Church being an ally of the state, a Church that these political groups controlled according to their whims and interests. The traditional Church not only did not criticize the behavior of these elites, but even legitimatized it. Therefore, in June 1969, a few months after having received the Pope in Bogotá, then-Colombian President Carlos Lleras Restrepo, his Ministry of Foreign Relationships Alfonso Lopez Michelsen, and his Ambassador Misael Pastrana Borrero paid a state visit to President Richard Nixon. Although they discussed other matters in this visit, Lleras Restrepo denounced the Latin-American Church as one of the sources of radicalness in the continent. “President Lleras said that many of the bishops and priests in several countries had been involving themselves in university, work and student matters, so they were using the same slogans and concepts than Marxists. Thus, these groups were talking about imperialism and capitalist exploitation” …” He thought that many of these clergymen were influenced by Marxists. (…) President Lleras observed that some of the foreign missionaries, like some priests from Maryknoll, for example, took up this kind of revolutionary line. (…) President Nixon said that he would like the Rockefeller mission to inform him about the Church and the role it has been playing in Latin America.” (U.S. National Archives and Record Administration V 78 Visit of President Lleras of Colombia, June 12-13, 1969. Admin. And Substantive Miscellaneous, Briefing Book. ARC Identifier 3999781-3999783 Record Group 59, Visit Files 1966-1970 in particular-Farewell Call of President Lleras. White House, June 13 1969). Reproduced from the open files of the Nixon Presidential Material Staff/Declassified A/ISS/IPS Department of State E.O. 12958, as amended September 4. 2008.

The international and local media kept on targeting any actions or speeches considered radical from the Latin-American Christians whether they were bishops or laity, and after the Rockefeller report was published, the criticism increased. In the context of the Cold War and the dictatorships in the 60s and 70s in South America, including the wars in Central America in the 80s, the simplification of what was happening in the Church justified the Latin American persecution and martyrdom, both of Catholics and Protestants.

Inside the Church, which has never been homogeneous, but with different trends, an important turning point occurred when conservative groups led in Latin America by Alfonso López Trujillo, executive secretary of the Latin American Episcopal Council (CELAM), took control in 1973, bolstered by the arrival of staunch anti-Communist Pope John Paul II in 1979. In the Episcopal Assembly in Puebla in 1979, the confrontation was strong. Although the conservatives were not able to drown out the bishops interested in carrying forward the decisions taken in the Second Vatican Council and the meeting of Medellin, when these progressive bishops reached retirement age, they were speedily replaced by others aligned with John Paul II’s new vision. These new bishops changed the pastoral’s path and those priests and sisters who still followed the proposals of the Council and Medellin, were required to leave the parishes where they served the poor. Theologians, like Leonardo Boff and Ivonne Guevara were silenced, even including the charismatic Dom Helder Camara who traveled around the world denouncing the Brazilian military dictatorship and its systematic violation of human rights because John Paul II thought he alone should be the Church’s only international voice. At the same time all those young workers, student and peasant movements and the ecclesiastic grass root communities that had been the grand pastoral strategy of the Church up until 1980 were discouraged. On the other hand, new ecclesiastic movements and communities with a more spiritualistic style were strengthen and encouraged.

Some of them gave good results, but others controlled by charismatic figures like Marcial Maciel, from the Legionnaires of Christ in Mexico and Luis Figari from “Sodalicío de la Vida Cristiana” in Peru, eventually found themselves involved in big sexual scandals inside the Church. These and other priests caused a huge credibility crisis not only in the Church but in society too.

The vacuum created by the Catholic Church in the periphery, due to the political and religious persecution of the priests and nuns who had responded to the call by the progressive bishops and were later expelled by the conservative faction, began to be filled by non-Catholic Christian churches.

All of the non-Catholic Christian movements, (Protestants, Evangelicals, Independents, Pentecostals, and Neo-Pentecostals) began to be lumped together under the name of “evangelical,” even though most are Pentecostal, with an important escalation in the last decades of the 20th century and the first ones of the 21st century. At the beginning of the 20th Century, non-Catholics in Latin America were fewer than 1% of the population. According to a Pew Research Center report, that percentage had increased to 19% by 2014.

The non-Catholic missions had arrived long ago, but they moved from the countryside to the cities in the second half of the 20th century, speeding up the expansion of the Pentecostal movement. The dynamics of these churches allowed them a speedy social and spiritual insertion among the poor. They are organized around the personal leadership of pastors who are themselves part of the communities, without the long and complex training process of the Catholic priests and pastors from the historical Protestant churches. This situation not only facilitates the increase of numbers of pastors but, also their communication and relationship with the large slums on the outskirts of cities. The Pentecostals possess a message they swiftly mixed with the local beliefs, and they have a very flexible theology and liturgy that facilitates speedily their expansion among different sectors of the population through the use of a broad range of media and technological systems.

In a very short time they not only fill up the vacuum left by the Catholic churches but also many Protestant and Evangelical historical churches adopted the Pentecostal creed. The theological axis of the Pentecostal movement—since we are not talking about a centralized Church—affirms that the actions of the Holy Spirit allows the specific transformation of any cause of suffering which in turn not only allows the overcoming of social, family, and economic troubles but also presents it as evidence of the presence of the Holy Spirit in people’s lives. Contrary to liberation theology, these developed a theology of prosperity based in the belief than the more a person pays or how frequently he or she pays the tithe the more possessions he or she will receive.

However, even though these groups are the majority, not all the non-Catholic Christians or Evangelicals agree with this vision. Some have allied themselves with Catholic groups like conservative parties, democratic and progressive parties, and others that are openly revolutionaries.

Liberation theology continued to flourish in the academic spaces of some universities like the Central American University and through theologians’ associations such as the Iberoamerican Group of Theology or the Amerindian Network that brings together theologians from Latin America and the Caribbean. Even though Amerindia is a network of Catholic origin, it has an ecumenical spirit t open to interreligious dialogue and cooperation. The group revived the ecclesiastical tradition of helping the poor and the marginalized and has proposed new models to make the Church more communal and participative, accordingly to liberation theology as a contribution to the universality of the Church.

On the other hand, CELAM reassumed in the episcopal conference that took place in Aparecida, Brazil, in 2007 the fundamental guidelines outlined in the conferences of Medellin (1968), Puebla (1979) and the synods of the Americas and of Amazonia (2019). All of the above combined with Pope Francis’ efforts to reassume important aspects proposed in the Second Vatican Council like building a Church of and by the poor, synodic, in other words, so that believers, priests, nuns and bishops all walk together to seek a greater faithfulness to the message of Jesus taking in consideration the huge contemporary challenges.

El cristianismo entre la transformación religiosa

Su impacto en la política latinoamericana

Por Ana María Bidegain

En la segunda mitad del siglo 20, América Latina fue sorprendida por cambios religiosos que no sólo estaban transformando el panorama religioso, sino también influyendo en la sociedad y la política.

Desde la década de 1950 algunos miembros de la iglesia católica—no solamente sacerdotes y religiosos, sino obreros, campesinos y estudiantes—se comenzaron a inquietar por el retorno al régimen de cristiandad establecido entre el estado de bienestar y la iglesia en los países latinoamericanos. Es decir, hasta entonces, el estado propiciaba los medios materiales y la iglesia cumplía labores sociales como la educación, la salud, asistencia a los desamparados, que normalmente correspondería al estado, y al mismo tiempo lo legitimaba. Esa había sido la manera en que había llegado el cristianismo a estas latitudes, pero no era el modelo del cristianismo primitivo.

Paulatinamente, los que estaban molestos con el régimen de cristiandad buscaron el retorno a las fuentes, es decir, a la Biblia y los modelos del cristianismo primitivo para buscar como vivir el cristianismo en la realidad particular de América Latina en el siglo 20. Algunas diócesis, grupos de sacerdotes y religiosas empezaron a realizar cambios pastorales que permitiera dar una respuesta más coherente entre el mensaje cristiano y el contexto de la realidad latinoamericana—pobreza, violencia e inequidad. Pero sobre todo fueron movimientos juveniles de obreros, estudiantes y campesinos, que formando pequeñas comunidades de base en las analizaban la realidad circundante y sustentados en la Biblia y la doctrina social propiciaron nuevas visiones y maneras de encarar la misión de la iglesia.

En Brasil, por ejemplo, en 1960, en un congreso de los universitarios católicos, la junta de la Juventud Universitaria Católica (JUC), presentó una ponencia en la que, al VER la realidad socioeconómica y política, Juzgaron la necesidad de transformación social dada la realidad de enormes injusticias sociales y políticas. Por tanto, decidieron ACTUAR comprometiéndose a cambiar esa realidad. Cambios que implicaban reforma agraria, combate a los monopolios capitalistas, liberación nacional de las injerencias internacionales, la reforma del sistema educativo.

Se sustentaron en autores cristiano, que el movimiento había venido trabajando, desde Tomas de Aquino hasta los filósofos franceses Jacques Maritain y Emmanuel Mounier, pasando por varias encíclicas sociales de los Papas en el siglo XX. Pero sus conclusiones resultaron novedosas y superaron la visión tradicional de la doctrina social de la iglesia o los puntos que defendía la democracia cristiana. El documento sorprendió a muchos de los obispos conservadores brasileños que observaban el crecimiento de esta organización juvenil y empezaron a prender alarmas por la posible infiltración marxista o por el uso de un lenguaje marxista al interior de la propia iglesia.

Sin embargo, reuniones oficiales de la Iglesia como el Concilio Vaticano II (1962-1965) y continentales como las de los obispos latinoamericanos en Medellín (1968) y Puebla (1979), dieron sustento para que los fieles de toda condición social y racial formaran también pequeñas comunidades en todas las parroquias. Como resultado, en muchas de ellas empezaron a vivir el cristianismo de una forma práctica y poderosa, comprometiéndose a transformar las situaciones de injusticia social que afectaban a los más pobres.

Hace exactamente 50 años, en Lima, Gustavo Gutiérrez publicó Teología de la Liberación, inspirado en su trabajo pastoral acompañando las comunidades de base en su parroquia, en un barrio humilde de Lima, pero también en la caminada de los estudiantes y profesionales a quienes asesoraba tanto en Perú como en el resto de América Latina. Sin embargo, su experiencia no fue única. En los 60 y los 70, autores como Juan Luis Segundo en Uruguay, Lucio Gera y José Miguez Bonino en Argentina, Leonardo Boff, e Ivone Guevara, Rubén Alves en Brasil, Jon Sobrino y Elsa Tamez en Centro América, entre muchos otros, publicaban trabajos teológicos en una perspectiva similar y mucha gente hablaba de la teología de la liberación.

Hoy día, hay muchos que dicen que la teología de la liberación está muerta. Pero no, no está muerta. Las ideas no se matan. Pero si mataron a muchos de los fieles y pastores que fueron sus inspiradores y seguidores. Así como en sus inicios se quiso matar al cristianismo y durante siglos mataron a cristianos acusándolos de crímenes que no habían cometido, ha sucedido con el movimiento eclesial articulado con la teología de la liberación.

La teología es un esfuerzo intelectual sobre la manera que los humanos pueden vivir la experiencia de Dios. La teología pastoral, como es la de la liberación, es ante todo una reflexión, y si se quiere una sistematización, de la experiencia, de la manera de vivir el cristianismo. En este caso, la manera de vivirlo en la segunda mitad del siglo 20 en América Latina. Pero también en otros lugares del mundo, porque la teología de la liberación es producto de la historia cristiana universal y no sólo católica. Por eso, en otras iglesias cristianas como la Presbiteriana, Luterana o la Metodista también hubo una transformación eclesial y una producción teológica en la misma línea y también denominada de la liberación.

Tradicionalmente la teología usaba como sustento diversas propuestas filosóficas en los 60’s estos grupos cristianos y los teólogos en particular dialogaban con la realidad social y las ciencias que nos ayudan a comprenderla. Por ejemplo, los estudios de la CEPAL en los 60’s, la teoría de la dependencia; la mirada sobre la historia de América Latina desde la perspectiva de los pobres, que propuso el filósofo argentino-mexicano Enrique Dussel. Se convertieron en los primeros esbozos de lo que hoy conocemos como teoría de la decolonialidad fueron usados por las comunidades y por los teólogos para realizar las primeras elaboraciones teológicas que se denominaron teología de la liberación y una teología latinoamericana realizada por mujeres. En ocasiones, usaban conceptos marxistas para enunciar y explicar la realidad social. Los esfuerzos teológicos latinoamericanos, aunque no invalidan el diálogo con la filosofía, dialogan con las otras ciencias humanas y sociales. Por tanto, es una mirada interdisciplinaria la que brinda los mayores sustentos a los y las teólogas, para entender y explicitar la experiencia de Dios entre las poblaciones empobrecidas de América Latina.

Hagamos un poquito de historia para explicar que la teología de la liberación no fue ajena al conjunto de la Iglesia, pero por que fue perseguida, por que algunos dijeron que estaba muerta, y sin embargo y por qué sigue viva y vigente.

Second Meeting of the Conferencia Episcopal Latinoamericana // Reunión de la Segunda Conferencia Episcopal Latinoamericana, Seminario Mayor de Medellín, de 1968

En 1891, con la encíclica Rerum Novarum, (Nuevas realidades) de León XIII, se retomó la exigencia cristiana de leer la realidad social donde se vive y de atender a los que en ella sufren y viven en vulnerabilidad. Como resultado, en el siglo XX, a través de muchas otras encíclicas sociales, varios Papas profundizaron esta perspectiva que dio vida a la doctrina social de la iglesia, pero también a una pastoral que acompañara los grandes desafíos sociales que trajo el siglo. Uno de ellos era la situación social y la secularización creciente de la clase obrera cada vez más influenciada por el anarquismo, el socialismo y el comunismo.

Para atender tamaño reto, poco antes de la primera guerra mundial, Joseph Cardijn, cura en una parroquia con amplia población obrera en las afueras de Bruselas, Bélgica, desarrolló una nueva pastoral orientada a que la evangelización la hicieran los mismos obreros entre ellos, para ellos y por ellos mismos formando pequeñas comunidades en sus lugares de trabajo. Luego la experiencia se expandió por Europa, Norte América y en los 30 y 40 llegó a América Latina. Partían por ver, entender, explicitar sus problemas cotidianos, entre los que sobresalían la necesidad de luchar por sus propios intereses dentro de un sistema económico injusto y que no brindaba ninguna protección social. Al mismo tiempo surgía la pregunta: ¿cómo Jesús hubiese reaccionado ante esta situación? ¡Si es injusta es una realidad de pecado! ¿Qué nos dice el mensaje evangélico? ¿Cómo enfrentar esta realidad de pecado?

Así surgió VER, JUZGAR, ACTUAR. Esta nueva pastoral, usada entre los obreros y particularmente entre los jóvenes, se empezó a utilizar entre otros sectores sociales como estudiantes, profesionales, campesinado—incluyendo tanto a hombres como a mujeres. Del espiritualismo desencarnado se pasó a una espiritualidad en la acción. Ello dio origen a nuevas organizaciones al interno de la iglesia como a importantes movimientos sociales cristianos, que al comienzo apoyaron a la Democracia Cristiana por ser esta también inspirada en la doctrina social de la iglesia.

Pero como dijimos, muchos cristianos comenzaron a criticar el modelo de cristiandad en la cual seguía encuadrada la Democracia Cristiana y su incapacidad para formular cambios sociales más profundos y rápidos. Por eso, en los 60’s rompiendo con la Democracia Cristiana, surgen movimientos de universitarios, obreros y campesinos más radicales de inspiración cristiana como la Acción Popular en Brasil, el MAPU (Movimiento de Acción Popular Unitaria) en Chile y en Uruguay y muchos otros.

Por su parte, algunos obispos, en la mayoría de los países latinoamericanos buscaron el sustento de la sociología para tratar de VER, de entender con mayor profundidad tanto la realidad social en la cual debían actuar como la necesaria reorganización de las propias diócesis y se buscó con la pastoral de conjunto integrar el trabajo de clero diocesano, órdenes y congregaciones religiosas y movimientos de laicos. Así fueron abriendo el camino de la sinodalidad, es decir de caminar juntos como Pueblo de Dios, (todos los cristianos en igualdad) conceptos que desarrolló el Concilio Ecuménico Vaticano II.

Un concilio es la reunión o asamblea de obispos de todo el mundo, por eso ecuménico que significa universal, para tratar asuntos que señalan el camino de la iglesia. En el Concilio Ecuménico Vaticano II, además de los obispos participaron teólogos, como consejeros y representantes de órdenes religiosas, de organizaciones laicas, personas de otras religiones y denominaciones cristianas a quien invitó el Papa Juan XXIII como auditores. Por iniciativa del Cardenal Joseph Suenens, de Bélgica, el Concilio invitó como auditoras, también a 21 mujeres laicas y religiosas. Fue convocado por el Papa Juan XXIII en 1959 para establecer un mayor diálogo con el mundo moderno y dar una respuesta renovada desde la perspectiva de la Iglesia y de cara al futuro en un mundo de constante cambio. Se trataron temas referentes a la renovación interna de la iglesia, pero Juan XXIII habló desde el inicio de la necesidad de atender los “Signos de los tiempos” entre los que destacó, la realidad de los pobres y de los obreros, los países del llamado Tercer Mundo y la realidad de las mujeres. Se realizó entre 1962 y1965, y debido al deceso de Juan XXII en 1963 debió terminarlo Paulo VI. Se promulgaron cuatro importantes constituciones, entre la que destaco- por el impacto que tuvo para América Latina en referencia al tópico que estamos desarrollando la referente a la Iglesia en el mundo Gaudiun et Spes (Gozo y Esperanza). Igualmente, entre los nueve decretos: la actividad misionera de la iglesia, la actividad del apostolado de los laicos, la renovación de la vida religiosa, la relación con otras denominaciones cristianas y tres declaraciones como la referente a la libertad religiosa, la educación cristiana y la relación de los católicos con otras religiones no cristianas fueron recibidas y muy comentadas en América Latina.

Pope Paul VI received by President Carlos Lleras Restrepo // Papa Paulo VI recibido por el Presidente Carlos Lleras Restrepo, en Bogotá, agosto 1968

La asamblea de los obispos latinoamericanos reunidos en Medellín en 1968 se encargó de aterrizar las propuestas del Concilio al contexto latinoamericano. Hablaron con claridad sobre la realidad latinoamericana que caracterizaron en uno de sus documentos como de violencia institucionalizada y reconocieron que por ello la mayoría de la población latinoamericana vivía en la pobreza. Propusieron que todas las diócesis adoptaran las nuevas orientaciones pastorales y que desde las parroquias se organizaran las comunidades eclesiales de base usando la metodología de Ver, Juzgar y Actuar. Por eso surgieron, no pocas organizaciones y movimientos sociales de inspiración cristianas luchando por salarios justos y por servicios básicos como energía, agua potable y transporte en las áreas urbanas y por tierras y agua en zonas rurales. En no pocas ocasiones disputaron el espacio con movimientos y partidos políticos marxistas y revolucionarios y en otras se aliaron con ellos para lograr objetivos que consideraban justos.

Tanto los mensajes contundentes de líderes religiosos como las movilizaciones que estaban provocando no fueron bien recibidas por sectores políticos acostumbrados a tener una iglesia aliada al estado, que esa misma elite económica y social organizaban a su antojo e interés, y que no criticaba su acción, sino que la legitimaba. Por eso, en junio de 1969, pocos meses después de haber recibido al Papa en Bogotá, Carlos Lleras Restrepo, entonces presidente de Colombia, hizo una visita de estado al presidente Richard Nixon acompañado de su ministro de Relaciones Exteriores, Alfonso López Michelsen y su embajador Misael Pastrana Borrero, aunque se trataron otros temas en esta visita, Lleras Restrepo denunció a la iglesia latinoamericana como una de las fuentes de la radicalidad en el continente. “El presidente Lleras dijo que muchos de los obispos y sacerdotes en varios países se habían involucrado en asuntos universitarios, laborales y estudiantiles, utilizando los mismos lemas y conceptos que los marxistas. Por lo tanto hablaban de imperialismo, y explotación capitalista.”…”El pensaba que muchos de estos clérigos estaban influenciados por los marxistas. (…) El presidente Lleras observó que algunos de los misioneros extranjeros, por ejemplo, algunos de los sacerdotes de Maryknoll, habían tomado este tipo de línea revolucionaria. (…) El presidente Nixon dijo que le gustaría que la misión Rockefeller informara sobre la Iglesia y el papel que esta desempeña en América Latina” (U.S. National Archives and Record Administration V 78 Visit of President Lleras of Colombia, Junio 12-13, 1969. Admin. And Substantive Miscellaneous, Briefing Book. ARC Identifier 3999781 – 3999783 Record Group 59, Visit Files 1966-1970 in particular; Farewell Call of President Lleras. White House, June 13 1969). Reproduced from the open files of the Nixon Presidential Material Staff/ Declassiffied A/ISS/IPS, Department of State E.O.12958, as amended September 4. 2008.

Paulatinamente y sobretodo después de la publicación del informe Rockefeller, los medios internacionales y locales no dejaron de poner la mira en las acciones y discursos de los cristianos en América Latina, que pudieran ser radicales, desde los obispos hasta el laicado.

Dentro del contexto de la Guerra Fría y de las dictaduras de los 60 y 70 en América del Sur y las guerras de los 80’s en Centro América, la simplificación de lo que sucedía en la iglesia, justificó la persecución y el martirio latinoamericano, incluyendo Protestantes y Católicos.

Third Congreso Continental de Teología organized by Amerindia at the UCA // III Congreso Continental de Teología organizado por Amerindia en la UCA San Salvador, en Agosto, 2018

Al interior de la propia Iglesia, que nunca ha sido homogénea, sino que hay corriente en su interior, se produjo un viraje importante y tomaron el control sectores conservadores liderados en América Latina por Alfonso López Trujillo, desde 1973 Secretario Ejecutivo del CELAM y Juan Pablo II desde 1979. En la Asamblea Episcopal de Puebla de 1979 la confrontación fue fuerte y aunque no lograron eliminar a los obispos interesados en llevar adelante las decisiones del Concilio Vaticano II y de la reunión de Medellín, cuando cumplieron la edad de retiro, rápidamente fueron reemplazados por otros alineados en la nueva visión de Juan Pablo II. Estos nuevos obispos cambiaron el rumbo de la pastoral y los sacerdotes y religiosas que, siguiendo las propuestas del Concilio y Medellín, se les exigió salieran de las parroquias donde servían a los pobres. Teólogos y teólogas como Leonardo Boff e Ivonne Guevara fueron silenciados, incluso el carismático Dom Helder Cámara, —que recorrió el mundo denunciando la dictadura militar brasileña y su sistemática violación a los derechos humanos—porque Juan Pablo II consideraba que él debía ser la única voz internacional de la iglesia. Al mismo tiempo, se desestimularon todos esos movimientos entre la juventud obrera, estudiantil y campesina y las comunidades eclesiales de base, que había sido la gran estrategia pastoral de la iglesia hasta 1980. Por el contrario, se fortalecieron y animaron nuevos movimientos eclesiales y comunidades de corte más espiritualista. Algunos que han dado buenos frutos, pero otros controlados por figuras carismática como Marcial Maciel, para los Legionarios de Cristo en México, o en Perú, Luis Figari con Sodalicio de la Vida Cristiana, que a la postre resultaron envueltos en los grandes escándalos de abusos sexuales en la iglesia. Provocando estos y otros sacerdotes una enorme crisis de credibilidad tanto al interior de la iglesia como en la sociedad.

El espacio dejado por la iglesia católica en las periferias, debido a la persecución política y religiosa de los sacerdotes y religiosas que habían sido llamados por los obispos de corte progresista y luego expulsados y expulsadas por los conservadores, empezó a ser ocupado por iglesias cristianas no-católicas.

Todo el movimiento cristiano—no católico, (protestantes, evangélicos, independientes, pentecostales, neo-pentecostales)—desde hace unas décadas pasó a denominarse evangélico, aunque es mayoritariamente pentecostal y su crecimiento en las últimas décadas del siglo 20 y primera del 21 fueron muy importantes. A comienzos del siglo 20 el promedio de no- católicos para América Latina, no superaban el 1%. De acuerdo con el Pew Research Center, en 2014 es del 19%.

Las misiones no-católicas habían llegado mucho tiempo atrás, pero se movieron del campo a las ciudades en la segunda mitad del siglo 20, acelerando la expansión del movimiento pentecostal. La dinámica de estas iglesias permitió una inserción rápida social y espiritual entre los sectores populares. Están organizadas entorno al liderazgo personal de pastores surgidos entre miembros de las propias comunidades, sin el largo y complicado proceso de formación de los sacerdotes católicos, y pastores de las iglesias protestantes históricas. Lo que facilita tanto su multiplicación como la comunicación y relación con las enormes periferias urbanas, Poseen un mensaje que rápidamente articulan con las espiritualidades locales y tienen una teología y liturgia bastante flexible que facilitó rápidamente su expansión entre diversos segmentos de la población, unido al uso de una amplia gama de medios de comunicación y sistemas tecnológicos.

En poco tiempo, no sólo ocuparon el lugar dejado por las iglesias católicas, sino que muchas iglesias protestantes históricas y evangélicas se pentecostalizaron.

El eje teológico del movimiento pentecostal, porque no se trata de una iglesia centralizada, afirma que la acción del Espíritu Santo permite la transformación concreta de la realidad de sufrimiento, por tanto, superación de problemas sociales, familiares y económicos como evidencia de la presencia del Espíritu Santo en la vida de las personas. Frente a la teología de la liberación desarrollaron una teología de la prosperidad sustentada en el que más da—paga regularmente su diezmo—más bienes recibirá.

Es importante aclarar que, aunque son mayoritarios, no todos los cristianos no-católicos, o evangélicos, acompañan esta visión. Algunos han acompañado junto con sectores del catolicismo, tanto partidos de corte conservador, como partidos democráticos progresistas y otros abiertamente revolucionarios.

La teología de la liberación continuó su desarrollo tanto en el espacio académico de algunas universidades como la Centroamericana, como por teólogos como el Grupo Iberoamericano de Teología o la red Amerindia que reúne teólogos de América Latina y el Caribe, red origen católico, pero con espíritu ecuménico y abierta al dialogo y a la cooperación interreligiosa con otras instituciones. Recogen la tradición eclesial de opción por los pobres y excluidos, y la opción por nuevos modelos de iglesia comunitaria y participativa propuesta por la teología de la liberación como un aporte a la iglesia universal.

Por su lado, el Consejo Episcopal Latinoamericano (CELAM)—que lidera y orienta a la iglesia católica latinoamericana—desde el 2007 con la conferencia episcopal realizada en Aparecida, Brasil, ha retomado las líneas fundamentales trazadas en las conferencias de Medellín(1968) Puebla (1979) y Sínodos de las Américas y de Amazonía (2019) , acompaña el esfuerzo del Papa Francisco de retomar aspectos esenciales propuestos en el Concilio Vaticano II como construir una iglesia pobre y para los pobres, sinodal—es decir caminar juntos y juntas, fieles, sacerdotes, religiosas y obispos—para buscar una mayor fidelidad al mensaje de Jesús tomando en consideración los enormes desafíos contemporáneos.

Winter 2021, Volume XX, Number 2

Ana María Bidegain is Professor in the Religious Studies Department, at Florida International University. Bidegain’s main research focuses on Religion, Society and Politics in Latin American History, on which she has published extensively.

This article was translated by Bruno Cantellano.

Ana María Bidegain es Profesora Titular en el Departamento de Estudios de las Religiones en la Universidad Internacional de la Florida. Sus investigaciones se centran en temas relacionados con Religión Sociedad y Política, sobre lo cual ha publicado extensamente.

Related Articles

Indigenous Peoples, Active Agents

Recently, the Amazon and its indigenous residents have become hot issues, metaphorically as well as climatically. News stories around the world have documented raging and relatively…

Beyond the Sociology Books

If you are not from Colombia and hoping to understand the South American nation of 50 million souls, you might tend to focus on “Colombia the terrible”—narcotics and decades of socio-political violence…

Exodus Testimonios

The audience at Iglesia Monte de Sion was ecstatic as believers lined up to share their testimonials. “God delivered us from Egypt and brought us to the Promised Land,” said José as he shared his testimonio with the small Latinx Pentecostal church in central California…