Citizen Media

Mobile Phone Democracy

In October of 2009, my husband and I drove back down to Guatemala, the country of my birth, 3,118.5 miles, 53 hrs 1 minute of driving according to Bing maps, all the way from California. While I’d made similar drives with my mother, this time we weren’t headed down to bring back some family member or to be at the mercy of U.S. immigration officials to determine our legal status in the United States. This time we weren’t leaving because we were sick of being treated like mojados and maybe we just wouldn’t come back.

This time I was driving down to Guatemala as a Fulbright scholar, on a grant awarded by the U.S. State Department, making me a diplomatic representative of the United States (the irony doesn’t escape me). My Fulbright project was to research online citizen media and to create a collaborative citizen journalism website for Guatemalans to share information from their mobile phones to a website. With all my community organizing, nonprofit and journalism background, I was going down to listen, to learn and to orchestrate an online participatory space for civic issues in Guatemala.

I already knew that one of Guatemala’s biggest problems was internal communication (the reason why someone in Puerto Barrios has no clue what is happening in San Marcos), the lack of which is then exacerbated outside the country. Communication was prohibitively expensive so people often could not obtain information outside their municipalities. They often turned, as they do now, to community radio stations, many of them deemed pirate stations by the government. My family in the United States, myself included, wanted to know what was happening in Bananera, in Chiquimula, in Puerto Barrios, in Guatemala City. We wanted to share mundane events like the patron saint festivals, las ferias, the processions, and to find out news about catastrophes. Cheap, easy communication was essential for those living within the country and those trying to maintain a transnational connectedness.

It is also important to address communication and access when looking at the rise of citizen journalism, participatory media and citizen media—information produced by people who are not professional journalists or reporters. Affordability and ubiquitous access such as Internet cafes, Telecenters and mobile phones democratize information. For much of the time Guatemala and the rest of Central America weren’t part of the information revolution.

But communication has changed in Central America. Guatemala’s evolving mobile sector, representative of the region, shows how this technology can offer unprecedented participation in both local and global civic conversations and actions. It is presenting an opportunity for nation-building (however nascent) and democratization that neither the Guatemalan government nor U.S. and European foreign policy have been able to do.

It became obvious things had changed when Twitter user Jeanfer was arrested by Guatemalan authorities on the charges of “intent to incite financial panic” for sending out this tweet: “Primera acción real, ‘sacar el pisto de Banrural’ y quebrar el banco de los corruptos.” “First real action, ‘to take the money out of Banrural’ and break the bank of the corrupt.” He was arrested and spent the night in jail, whereupon the Twitter community raised funds to help him pay for a lawyer. In the same month that many human rights and mining activists had received death threats via SMS (the acronym for Short Message Service or “text messages,” prominent lawyer Rodrigo Rosenberg, allegedly fearing he would be killed, recorded a YouTube video blaming President Colom and his wife for such a deed. The video was released the same weekend Rosenberg’s body was found shot in Guatemala City’s wealthy Zone 10.

These examples show how the privatization of telecommunications creates a competitive market for citizens to express themselves, to communicate and to access much needed information. In many ways it’s an awakening in Guatemala, to the first “brick” or foundation of a democratic society, of the right to express one’s opinion publicly and for that opinion to play a role in one’s own community and in self-governance.

A social fabric or an imagined social community is being spun from pixels—thousands of people who are creating their own WordPress.com or Blogger.com, creating civic group Facebook fan pages like Movimiento Cívico Nacional and Voces de Cambio, organizing collective actions on Twitter and Facebook like the protests in Guatemala City asking President Colom to step down because of Rodrigo Rosenberg’s YouTube video allegations. There are Twitter hashtags to follow impunity efforts, national emergencies, traffic, weather, tax season.

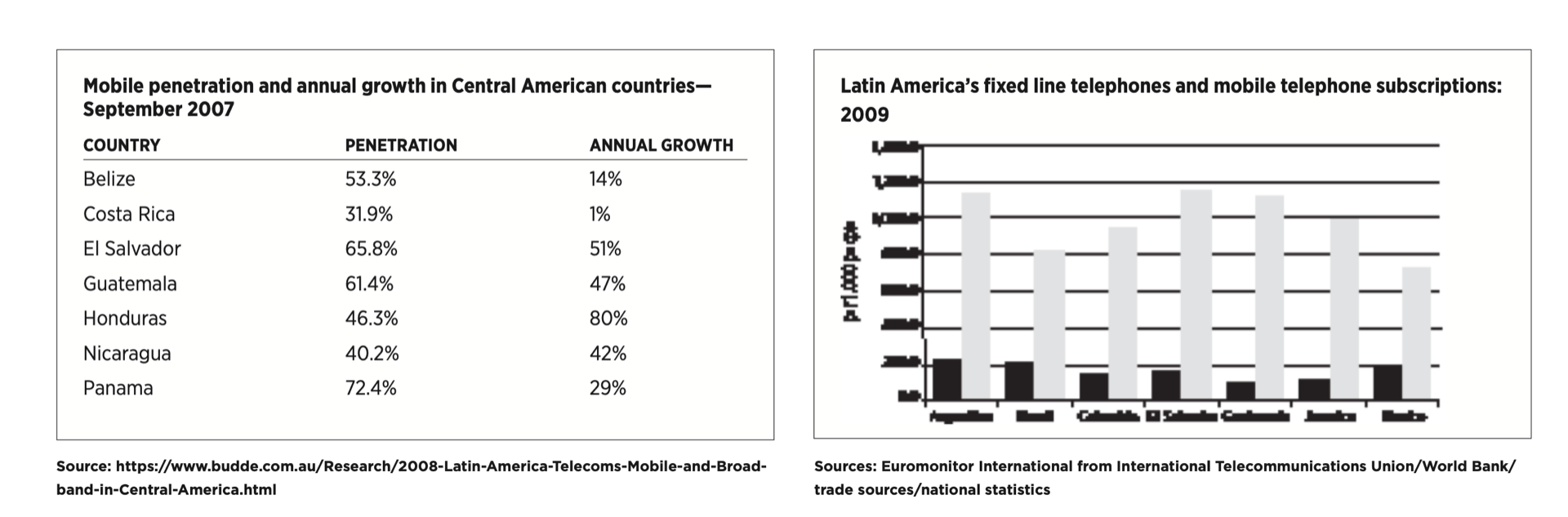

In many developing and emerging markets with a lack of infrastructure and investment in traditional communication networks such as landlines and other cable-dependent communication, the telecom sector leapfrogs into the mobile phone arena. Investors, government and consumers shift quickly toward mobile communication because of convenience, affordability, and accessibility. The table on the following page illustrates the surprisingly large penetration rate and the very impressive annual growth rate in Central American countries.

This development means that the new technology is received with much more ease than in already existing well-established communication markets. This process has been helped quite a bit by the surrounding countries of Brazil, Venezuela and Mexico, as seen in the table below.

I got a glimpse of how much Guatemala’s telecommunications had changed in 2006 on a reporting assignment on deforestation in Petén. On the top of an excavated Mayan pyramid called El Tigre, one of three pyramids in a remote archaeological site deep in the Guatemalan jungle of Mirador Basin, I rested my legs weary from hiking 27 miles in 90 degree heat. I was barely able to raise my head enough to see someone holding up a mobile phone. Josué Guzmán was one of the Guatemalan archaeologists I was accompanying into this ancient Mayan city and he was sending a text message to his girlfriend.

“In Guatemala we’re very connected,” he told me. That’s when I started to believe that mobile phones and the developed telecommunications industry in Guatemala were one of the reasons for this interconnectedness. It gave me faith in mobile technology as a tool for journalism and democratic development. At that moment I imagined what news would look like if everyone who had a mobile phone or at least access to one, could send, share, distribute and report events they witnessed via a mobile phone to a website and also receive that information. I soon realized that long after the asphalt and pavement ends, the mobile phone networks in Guatemala extend deep into the mountains, with 99.7 percent penetration of mobile service in a country with an estimated population of more than 14 million in 2009, according to the World Bank Development Indicators. In 2007, the Superintendencia de Telecomunicaciones (SIT) registered 4.7 million more mobile users, indicating that 9 out of every 10 Guatemalans own or have access to a mobile phone. Much to the surprise of many of its Central American neighbors, Guatemala’s telecom sector is one of the top four in Latin America, according to Fundación2020 consultant Mario Marroquín Rivera. This figure contrasts with high-speed Internet access at only 7.7 percent and highly concentrated in large urban areas.

In 2001, Appalachian State University anthropologist Tim Smith traveled to Guatemala to research social movements and democracy among indigenous communities. “I had Mayas asking for my cellphone number and pulling out their flip Motorola when in 1997 and 1998 I had to get on a bus and show up to their houses and that was the way to get in contact with anyone,” said Smith, who is currently traveling in Guatemala studying post-war Maya activism and electoral politics. Smith believes all this texting, blogging, and buying of smartphones will lead to big changes.

“Part of me wants to say something along the lines of the use of mobile phones and now online networking sites for democratic participation and mobilization in this election coming up is probably akin to the rise of print capitalism in Latin America,” he observed.

Smith believes Guatemala should be seen as a model in the use of this technology in the upcoming election in August 2011—in particular the use of these tools by ordinary citizens who are using the Internet and smartphones and blogging to get vital information out. “Mayas are sitting in Mayan-owned and operated Internet cafes blogging in Maya and texting; it was unimaginable ten years ago! It has the potential to shake up the election and not lead us to another 1999 result.” Mobile phones lessen the urban-rural dichotomy, allowing communities to organize themselves.

News organizations such as Emisoras Unidas, Radio Sonora and El Periódico provide breaking news via text or SMS alerts and ask listeners to contribute news, comments and traffic reports that are often read out on-air. During a major four-hour electrical blackout that affected 17 departments in October 2009, people texted in their messages to radio stations that were reading them out loud while listeners tuned in via their $10 mobile phones bought at the local market.

For the National Movement of Radio Stations—representing 20 of the 22 departments and 168 radio stations—mobile phones are vital tools for airing local broadcasts in indigenous languages. In late January I witnessed about two dozen community radio stations’ volunteers crowding around a speaker to broadcast live from their mobile phones to their communities from Guatemala City’s Congress. Every few minutes they would translate by phone into their community’s language, and then put the mobile phone back to the speaker. On the other end was the station volunteer putting the mobile phone the radio reporter had called on to the microphone that was connected to the radio transmitter and the message was broadcast live. It was their version of the “one to many” model, and their mobile phones were the intermediaries making that possible.

Some municipalities such as Mazatenango and Chinaulta use Twitter to deliver local news and events. Guatemala City sends out traffic alerts throughout the day to Twitter and users also contribute news about protests, blockades and construction on the roads. Mobile phones also provided a trail during CICIG’s investigative work in tracking the truth about the murder, later uncovered as a plotted suicide, of Rodrigo Rosenberg.

Twitter in Guatemala only works via online access or other enabling applications. As more smartphones are sold —including the recently introduced Android-powered models—more people are able to browse and use mobile phones beyond just telephony. For example, anyone can buy a mobile phone in Guatemala without a plan, deposit or credit, pre-pay saldo or funds, and sign up for unlimited WAP by texting 805 “wap.” For about 60 cents daily, that person can browse the Internet and have unlimited access. That’s cheaper than texting and MMS.

This trend in Central America falls in line with the trend in the rest of the world. The next two billion Internet users will be people who make less than $4,000 a year, according to Don Derosby of Monitor GBN. “It’s not about the network, it’s about the cheap mobile device,” he stated in his report on “The Evolving Internet: Driving Forces, Uncertainties and Four Scenarios to 2025” at UC Berkeley’s School of Information in 2010. “That future is already here, maybe unevenly distributed, but here.”

The numbers above clearly show that penetration and growth are rising in Central America, and are making some people in Latin America, like Mexican businessman and media mogul Carlos Slim, extremely wealthy. The region welcomes information services that are transformative because they provide a quantum leap for disadvantaged individuals, enabling them to participate in governance, to gain an economic advantage, to transmit culture, to create literacy and to make the unattainable, attainable.

Spring 2013, Volume XII, Number 3

Kara Andrade is an Ashoka fellow working in Central America. Previously she was funded by the U.S. State Department to implement a mobile-based citizen journalism website called HablaGuate. She was the community organizer for Spot.Us, an open source project that focuses on community-funded reporting. She graduated from the University of California at Berkeley with a Master’s in Journalism and has ten years of experience in nonprofit development, public health and community organizing. She has worked as a multimedia producer and photojournalist for Agence France-Presse, France 24, the Associated Press, the San Jose Mercury News, Contra Costa Times and the Oakland Tribune.

Related Articles

New Journalists for a New World

I received a surprising phone call one day in late 1993, when I was the director of Telecaribe, a public television channel in Barranquilla, Colombia. The caller was none other than Gabriel García Márquez. “Will you invite me to dinner?” he asked me. “Of course, Gabito,” I…

Latin American Nieman Fellows

A few days after I arrived at Harvard in August 2000 to begin my work as curator of the Nieman Foundation for Journalism, Tim Golden, an investigative reporter for the New York Times in Latin America, phoned me. “Could I find a place in the new Nieman class for a Colombian…

Freedom of Expression in Latin America

In June 1997, Chile’s Supreme Court upheld a ban on the film “The Last Temptation of Christ,” based on a Pinochet-era provision of the country’s constitution. Four years later, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights heard a challenge to this ban and issued a very different…