Citizens and Property Rights

Average crime rates in Latin American cities are the highest in the world. How is this problem being handled? Many people think that the only existing legal strategy is criminal law. Criminal law deals with violent crime by pursuing criminals through police work, trying them in the courts, and, after conviction, putting them in jail. However, I want to discuss another body of law that addresses the problem: property law. Property law deals with violent crime spatially. It operates most visibly in the creation of protected, often walled, spaces – gated residential communities, shopping malls, office parks – that confront violent crime not by reducing it but by ensuring that it takes place elsewhere.

The walls that surround privatized areas do more than relocate those identified as potential criminals, along with many others, to certain parts of the city . They have an important psychological impact on insiders. Insiders see them – and their accompanying video cameras, security guards, and alarm systems – as their primary defense against crime. But the walls derive their legal meaning from property law. Property law, simply by itself, erects walls that protect insiders from outsiders. The very essence of one’s property right can be found in the words “Keep Out.” But physical walls add two important ingredients. They enable the enforcement of property rights by the property owners themselves, instead of requiring them to call the police. In addition, they enable the property owners to assert more extensive property rights against outsiders than those that the legal system actually authorizes because outsiders rarely challenge them.

The spread of walled areas in major cities raises a legal policy issue: what is the proper nature and extent of one’s property rights? To resolve this issue, it has to be decided whether these walled areas should be understood as more like one’s own house or rather as a city as a whole. Those who live or own property inside walled enclaves generally think of the enclaves as extensions of their own homes, stores, and offices. But as they grow larger and larger, they can become not just neighborhoods (as they are now) but entire cities. The right to exclude, as exercised by property owners, seems relatively uncontroversial in the context of one’s own house. But it would be odd indeed to treat São Paolo or Mexico City as private property. Even though historically there have been walled cities in Western society, it now seems unacceptable to attempt to wall off a whole city. What is the best way to think about these parts of town?

I think that these walled enclaves should be treated more like public space than they currently are. Beginning in the nineteenth century, property law in the United States required businesses that held themselves open to the public – such as innkeepers and common carriers – to serve the public as a whole without discrimination. Railroads and inns, it was decided, should not be allowed to favor some customers at the expense of others. In more recent times, hotels, theaters, and restaurants have been required to be open without discriminating on the grounds of race, color, religion, or national origin. This history suggests that a similar kind of openness can be required of shopping centers and office parks. Strict enforcement of laws prohibiting discrimination on the grounds of race and ethnicity would help open them to a wider variety of people. In addition, individuals exercising rights of free speech (religious evangelists, war protestors) and representatives of organizations seeking to reach employees working on the premises (union organizers, health care workers) could form the beginning of a list of uninvited strangers that would be free to enter these kinds of spaces. Restrictions could also be placed on the power of security guards to ask groups of people to leave the premises; groups of teenagers are often the target of such requests in shopping centers in the United States.

Unlike shopping centers and office parks, gated residential enclaves do not hold themselves open to the public. Even in these areas, however, the power to exclude outsiders should have its limits. The point is not to reject the idea that “one’s home is one’s castle” but to shift the location of the castle’s walls: the streets of residential communities should be open to more than just invited guests. The easiest way to begin, as the Supreme Court of the United States did in a case dealing with the company towns, would be to open these residential communities to people exercising their rights of free speech. This form of openness can readily be defended in terms of the public values that free expression represents. Simply admitting these outsiders would demonstrate to insiders and outsiders alike that walled communities cannot wall their residents off from the rest of society at will.

Would this interpretation of property rights in Latin America and elsewhere create a better world than one that allows walled enclaves to exclude anyone they choose? I think so. Low-crime and high-crime areas in every city can now be located on a map, and the areas adopting a policy of exclusion are usually the low-crime areas. As a result, no area in the city is truly “public.” The excluding areas are off-limits to those treated as undesirable, and much of the rest of the city is shunned by those accustomed to exclusion. Making walled areas more public will expand the number of places where people can become accustomed to the diversity of the population in the city in which they live. This experience would help reduce the level of tension people feel when they come into contact with unfamiliar kinds of strangers. And this reduced tension would enable a crime-control strategy that is the opposite of a reliance on exclusion. The principal security system of public places is the presence of people. Everyone knows, as Jane Jacobs argued 40 years ago, that “a well-used city street is apt to be a safe street [while] a deserted city street is apt to be unsafe.” These days, however, it’s hard to be confident that a stranger will help if a crime occurs because his or her own fear of being attacked generates a reluctance to “get involved,” even if all that is needed is a call to the police. Changing that attitude is an appropriate goal for the legal system.

Winter 2003, Volume II, Number 2

Gerald E. Frug, the Louis D. Brandeis Professor of Law at Harvard Law School, teaches Local Government Law. He is the author of City Making: Building Communities without Building Walls (1999).

Related Articles

Bogotá: A City (Almost) Transformed

The sleek red bus zooms out of the station in northern Bogota, a futuristic symbol of an (almost) transformed city. Nearby, thousands of cyclists of all ages enjoy a sunny morning on Latin America’s largest bike-path network.

Editor’s Letter: Cityscapes

I have to confess. I fell passionately, madly, in love at first sight. I was standing on the edge of Bogotá’s National Park, breathing in the rain-washed air laden with the heavy fragrance of eucalyptus trees. I looked up towards the mountains over the red-tiled roofs. And then it happened.

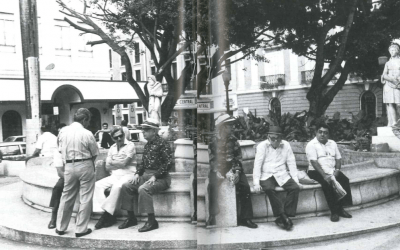

Social Spaces in San Juan

My city, San Juan, is a social city. Its character and virtue are best illustrated and defined by the collective and individual memories of its people and those places where we go to spend time in idleness….