Colombian Institutions

On the Paradox of Weakness

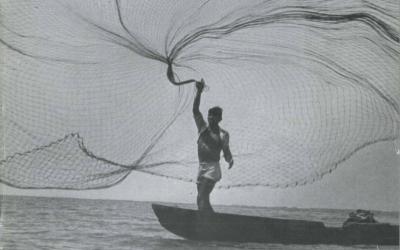

Father and sons. Photo by Jesus Abad Colorado.

On one of my recent journeys to Colombia, I bought a toy bus for my kids—a replica of the Transmilenio coaches, the modern line of public transport that crosses Bogotá from north to south in the Avenida Caracas. The toy was sold by street vendors, symbolizing a sort of civic pride that I immediately absorbed as I placed the little red coach in my hand-luggage with the enthusiasm of a child. Transmilenio is just one of the many achievements in the transformation of Bogotá, a city of seven million which, according to Washington Post correspondent Scott Wilson, “has become a pleasant anomaly, not only in a country where 3,500 died in war last year, but also across an unsteady continent whose capitals are urban horror stories.”

Despite the recent bombing of social club El Nogal and the incessant specter of terrorism, Bogotanos are turning into proud and generally optimistic citizens. It is certainly a pleasant experience to witness the city’s accomplishments. They are real and for everyone to see. An opinion poll published by El Tiempo (9/22/03) also suggests that Bogotanos view the capital’s institutions favorably. This picture of progress and confidence is in sharp contrast with generally held views of Colombia, often portrayed at the verge of breakdown. Thus the “anomaly” of Bogotá. Or is it?

Talk of state weakness in Colombia has become commonplace among academics and policy makers alike. The expression “a collapsing state” has fully entered the vocabulary of those who write about Colombia, both inside and outside the country. Other terms such as “delegitimation, “crisis of the social contract,” and “national disintegration” convey similar impressions. Those who think that the notion of “state collapse” obscures the origins of the crisis do not always offer an alternative, enlightening explanation; the roots of the problem are thus traced to supposedly fossilized institutions—the lack of structural change.

How weak are Colombian institutions? Is the country suffering from institutional collapse or from institutional inertia? Are the achievements of Bogotá an “anomaly” or the reflection of more complex developments?

THE VALUE OF WEAKNESS

It would be foolish to deny that the Colombian state has been historically weak. Measured against Max Weber’s classical definition, it cannot claim to have controlled the “monopoly of the legitimate physical force.”

By mid-19th century, the Colombian Army numbered the ridiculous figure of 500 men. In 1873 the military body increased to 1,000, an insignificant force for a country the size of France, Spain and Portugal combined. “The army can scarcely be said to exist,” concluded the then-British Minister in Bogotá. The development of a modern police was still far away. A thin army was mirrored in a thin bureaucracy: 1,451 public servants were employed by the central government in 1873; local states managed larger staffs, but the figures hardly added up to anything closer to a state apparatus for a country of three million people. The conservative regime that took over after 1885 made efforts to centralize power and expand the Army and the role of the state—in a paternalist attitude hand in glove with the Catholic Church. There were some successes but more frustrations. From 1899 to 1902, the country suffered the consequences of the Thousand-Day War (Guerra de los Mil Días), a tragic war that opened the way for Panamá’s secession.

Institutional modernization was therefore a latecomer to Colombia, the process only taking a firm hold in the first decades of the 20th century, although still at a relatively slow pace. Nonetheless, by the 1920s, a few significant inroads had been made. Older institutions were reorganized while new institutions were created: the professionalization of the Army was underway; a Central Bank was established. Although the national government gained some strength, it remained overall weak as political power continued in practice to be decentralized.

This brief historical sketch only serves to underline the point: the 19th-century left a deep legacy of state weakness in Colombia. A weak state represented a major problem for the maintenance of public order and for securing citizens’ rights. A tradition of a weak state, however, also impeded the monopolization of power by one single individual or sector of society, be it the infamous caudillos or the Army. What distinguished Colombia from its Latin American neighbors was the low profile of the military and the general absence of dictatorships.

INSTITUTIONAL RESILIENCE

A weak state did not mean an institutional vacuum. Among the most enduring creations of the 19th-century, the political parties stand out. Rooted in the early republic, Conservatives and Liberals took shape as identifiable organizations in 18491850. Their competitive struggles often immersed the nation in turmoil, but were also the bases of representative bodies—Congress, local city councils and departmental assemblies. They encouraged an electoral culture based on a wide suffrage with its own plethora of institutions, formal and informal. A tradition of a free press is closely linked to these developments.

The world recession unleashed by the 1929 stock market crash served as a significant test. One after another, with a few exceptions, political regimes broke down in Latin America. In contrast, Colombia underwent a peaceful alternation of power as Liberals displaced Conservatives from the Presidency in the 1930 elections. In 1939, as the shadow of totalitarianism spread in Western Europe and Latin America, Alberto Lleras Camargo—then the editor of El Liberal—could review with some pride, in an article in the newspaper, some of the achievements of his country’s democratic institutions.

Colombia could not be isolated from world trends. Nor had the nation overcome the bitter legacy of partisan sectarianism, fueled in the 1930s and 1940s by a confrontation between secular forces and the Catholic Church, among many other serious conflicts with 19th-century undertones. The assassination of popular Liberal leader Jorge Eliécer Gaitán on April 9, 1948 triggered a social explosion in Bogotá with widespread consequences.

Students of Colombia are probably familiar with the concept of “state collapse” in trying to understand the origins of “la Violencia” (1940s-1960s)—the bloody conflict that pitted Liberals against Conservatives, particularly in the countryside. Democratic institutions ceased to operate. The Police and the Army became heavily politicized. Impunity was rampant as the judiciary was ineffective, and arbitrary violence took over. Nevertheless, a recent study by historian James Henderson has called our attention to an extraordinary paradox that some may find hard to accept: that “most Colombian institutions grew significantly stronger during the years of violence.”

An impressive array of new private and public institutions were founded between 1945 and 1960, ranging from state agencies like the ICSS (the Colombian Social Security Insitute), Icetex (the Colombian Institute for Study Abroad), Ecopetrol (the Colombian State Oil Company); universities such as the Andes; private sector associations like the ANDI (National Industrialists Association); or radio networks such as Caracol.

To acknowledge these developments does not mean denying the horrors of an extremely painful conflict. The country entered into deep crisis. Prominent intellectual Luis López de Mesa did not exaggerate in observing that Colombia had suffered an “institutional heart attack” in 1949. The escalation of violence severely damaged the rule of law. As political parties lost control, the Presidency collapsed and the Army took power in 1953. But far from absolute paralysis or decay, society was growing in complexity. As Henderson suggests, some of those new institutions described above became “so effective that they were able to coordinate the bloodless coup” against the dictatorship in 1957. Conservatives and Liberals were capable of mobilizing the political nation to support, in a plebiscite under universal suffrage, the constitution that sealed the reemerging democracy in 1958.

BEYOND THE ANOMALIES

The National Front, originally planned to last for sixteen years (1958-1974), was a bipartisan power-sharing agreement designed to put an end to sectarian violence. It has long been a commonplace to denounce the anomalies of the regime as a picture of utter failure. A revisionist, less passionate view would offer a mixed record.

Liberals and Conservatives alternated the Presidency while seats in Congress and other representative bodies were allocated equally between them in an electoral system that excluded the participation of third minority parties. The two parties also divided up posts in the judiciary and the bureaucracy. But as political scientist Mario Latorre demonstrated in his superb study on the practices of the Front, third parties were never fully ousted. The growing perception, however, was one of exclusion, particularly after the decision to extend the National Front. The disputed results of the 1970 presidential elections also fed the revolutionary discourse of illegitimacy as a justification for the Marxist guerrilla groups that sprung up since the 1960s. Efforts to strengthen the national government developed alongside a process of increasing party fragmentation. This splintering was partially the result of an electoral system that prized intra-party over inter-party competition, but also the reflection of a decentralized polity where constant bargaining between the provinces and the center had historically been the norm. Nevertheless traditional parties did not disappear: they became vehicles of social mobility and the major instrument of what economic historian Miguel Urrutia has described as “a rather sophisticated form of clientelism.” Urrutia, currently the head of the Central Bank, sees the institutionalized party system as the key explanation for the successes of macroeconomic stability from the 1960s.

Colombian presidents had few incentives to embark upon irresponsible populist policies: their power was in any case limited by a complex web of party networks in Congress. Public opinion counted. Economic policies were subject to open debate, conditioning further the decisions of the authorities in the Treasury Ministry and the National Planning Department, institutions that became the niches of a modern technocracy. As Urrutia observes, the system was “not admired by national and foreign intellectuals” but by the late 1980s it had delivered “economic growth, an improved income distribution, and fairly progressive government expenditure.”

The National Front also partially succeeded in two of its major purposes. First, sectarian violence between Liberals and Conservatives was placated with homicide rates falling by the mid-1960s. Nevertheless levels of violence remained high, never returning to pre-1940s levels. New types of revolutionary violence emerged, now influenced by Cuban developments, as guerrilla groups spread: the FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia), ELN (National Liberation Army), EPL (Popular Liberation Army), M-19 (the April 19th Movement). Furthermore, violence rose to explosive levels in the late 1970s, triggered by the illegal traffic in drugs.

Second, civilians regained control of the state. But the army’s return to the barracks was followed by decades of relative civilian neglect of the institution: investment in the army as a proportion of GDP steadily declined, a trend only reversed in the 1990s.

As in the 1930s, the Cold War was another period of significant test and once again Colombian liberal democratic institutions survived while most political regimes in Latin American countries fell into the hands of the Army. Another paradox emerges: the struggle of Marxist guerrillas was fruitless in the face of the brutal dictatorships of the Southern Cone, yet they continued to grow under a democratic if imperfect regime in Colombia.

There were many imperfections in the regime, openly denounced in an intense debate. Pressure for reform did not come just from “outsiders.” As a university student in the 1970s, I eagerly read Nueva Frontera—the magazine directed by former President Carlos Lleras Restrepo with the assistance of Luis Carlos Galán, the Liberal leader later assassinated by the drug traffickers. Nueva Frontera led campaigns against clientelism, corruption and the decay of parties. The so-called “political establishment” did not remain still. Several administrations introduced substantial packages of constitutional reform into Congress, but their efforts were subject to the scrutinies of a system where the power of the executive is limited—by the legislature, the judiciary, and the electoral cycle.

The pace of reform accelerated after President Betancur launched his policy of “democratic apertura” in 1982, calling for negotiations with the guerrillas. Peace talks did not deliver much peace. Under his rule, however, the structure of political power was drastically changed: following the constitutional amendment of 1986, city mayors, instead of being appointed, would be elected by the popular vote. The movement for reform did not stop here. Betancur’s successors also attempted to bring the guerrillas back to the negotiating table. Frustration mounted. Nevertheless during the Gaviria government (1990-1994), a significant number of guerrilla groups demobilized in a process that led to the adoption of a fully new constitution in 1991.

AN ONGOING INSTITUTIONAL REVOLCÓN

I have consciously been selective in this long durée overview of Colombian institutions. I have risked what some may refer to as “conventional history.” Yet the “conventional wisdom” nowadays on Colombia tells the opposite story: tales of horror in a rapidly disintegrating country. Consider recent events: on August 7, 2002, while Alvaro Uribe took oath as the newly elected President, FARC mortars hit the area around the Casa de Nariño. You could focus your attention on the bombs, clear signs of the current disaster. You could also hold your breath, and ponder for a second an alternative image of the presidential inauguration: on how, in spite of being “besieged” by violent and powerful criminal organizations, the nation continues to select its rulers through the ballot box. For, as sociologist Eduardo Pizarro Leongomez suggests, it is the resilience of Colombian democratic institutions, not their apparent decay, that needs an explanation.

The historical record defies the vulgar view that Colombian democracy is a mere myth: in almost two centuries since independence, the number of years under dictatorship can be counted just with the fingers of two hands. Since then, the Congress in this “mythical” democracy has enjoyed a longer life than those in most countries on the continent, and indeed in Europe. Since then, Colombia’s mostly civilian presidents have come and gone following the regularity of the electoral calendar. Since then, a tradition of a free press has generally persevered, encouraging the formation of a public opinion that carries weight. During the 19th-century these democratic institutions helped Colombians to avoid tyrannical rule. During the 20th-century, they helped them to escape the waves of totalitarianism, populism and military dictatorship that swept both Europe and Latin America for decades.

Radical critics tend to ignore this record, often disparaged as a “rosy picture of the country,” in favor of a litany of vices: corruption, violence, misery, drugs, terrorism, party decay, guerrillas, paramilitaries and human rights violations. All these are real and serious problems. A genuinely reformist attitude to tackling them would have more chances of success, however, by acknowledging the achievements of Colombian liberal democratic institutions: they may offer the best and perhaps only way forward. That is unless one believes in miracles, the goodness of tyrants or revolutionary illusions.

Furthermore, a picture of fossilized institutions is simply false. Even if one takes the extreme view that Colombia remained stagnant since independence, or since 1958, it would be wrong to say that nothing has changed since 1991. Here we saw a true exercise of constitutional engineering, the results of which are too early to judge. This is not the place to examine the long list of new institutions that have framed Colombian daily life in the last decade. A recent collection of essays, edited by anthropologist and political scientist Francisco Gutiérrez Sanín, offers detailed analysis of the impact of those institutional changes on the parties—old and new—women, indigenous movements, local governments (Degradación o cambio: Evolución del sistema político colombiano, Bogotá: 2002). The authors are far from being complacent. Any complex reality—as they show—requires subtle judgements.

More subtle judgements are indeed necessary to distinguish where the ‘weakness’ of Colombian institution lies: to distinguish those that have remained stagnant from those that have modernized. The two traditional parties have been long suffering from decay—where not? Given the extraordinary dimensions of violence fed by organized crime—be it guerrillas, paramilitaries, or drug barons—state institutions to guarantee the security of citizens need to be strengthened. Even here change is taking place: the Police, the Army and the Judiciary are all undergoing processes of reform. The challenges, however, are as immense as the vast territories in the country demanding state attention, and the unpredictability and brutality of terrorism. And any effort to strengthen further the state will always face the limits imposed by a historical preference to be free from the state yoke.

Far from being an anomaly, the transformation of Bogotá is the most visible reflection of a country in flux, in an ongoing institutional revolcón—the popular expression to describe the substantial changes of recent years. From a distance, what often appears to be fossilized are not Colombian institutions but the very language used to examine national reality, past and present. At a recent cocktail party, while I was conversing with some intellectuals I had just met, I was criticized—in a cordial and amicable exchange of views—for defending “the decadent Colombian establishment.” There is no ‘establishment’ to defend: if it ever existed, it no longer does. Colombian liberal democratic institutions and traditions, however, are worth defending.

Eduardo Posada Carbó, a Colombian historian and journalist, graduated in Law from the Universidad Javeriana in Bogotá. He holds an M.Phil. in Latin American Studies and a D.Phil. in Modern History at Oxford University. He joined the University of Chicago as a Tinker Visiting Professor of Latin American History Spring 2003 and is currently an external adviser to the Fundación Ideas para la Paz, a Bogotá-based think-tank. He is a columnist in El Tiempo, the leading Colombian daily. His latest book is a collection of some of his essays, El Desafío de las Ideas: Ensayos de historia intelectual y política en Colombia (Medellín: Eafit and Banco de la República, 2003).

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter

This is a celebratory issue of ReVista. Throughout Latin America, LGBTQ+ anti-discrimination laws have been passed or strengthened.

Editor’s Letter: Colombia

When I first started working on this ReVista issue on Colombia, I thought of dedicating it to the memory of someone who had died. Murdered newspaper editor Guillermo Cano had been my entrée into Colombia when I won an Inter American…

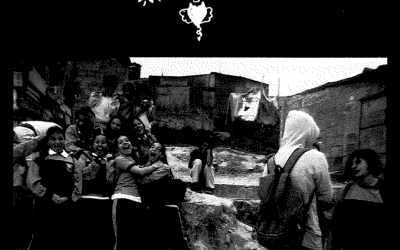

Photoessay: Shooting for Peace

Photoessay: Shooting for PeacePhotographs By The Children of The Shooting For Peace Project As this special issue of Revista highlights, Colombia’s degenerating predicament is a complex one, which needs to be looked at from new perspectives. Disparando Cámaras para la...