Colonial Cities

“Potosí!” exclaims Tom Cummins, his lively eyes twinkling, his neat graying ponytail just grazing his collar line. “You can’t have an issue on cities without Potosí. Some people think cities in Latin America just started yesterday. Potosí is incredible! It grew from nothing to a huge city overnight in the 1500s because of silver, and it’s twice as high as Mexico City. Now that’s a tale of a city!”

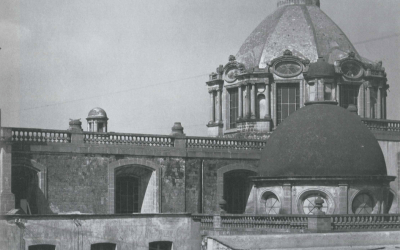

Thomas B. F. Cummins, Harvard’s Dumbarton Oaks Professor of Pre-Columbian and Colonial Art History, is sharing his passion for colonial cities spring semester by teaching the course “The Towns and Cities in the New World: The Architecture of Power” in the Department of History of Art and Architecture. The course examines the importance of the city in the 16th- and 17th-century New World. It traces the development and use of the grid plan as an artistic, religious, and political expression and looks at the architecture and decoration of churches that were the center of these towns, whether Quito, Cuzco, or Tlaxcala.

It’s Cummins’ first time teaching the course at Harvard, but he first begun a version of the course in 1996 at the University of Chicago. What’s apparent during a long conversation that starts off in his office in the Sackler Museum and ends up over coffee in a Starbucks is that the course is an ongoing process—just like cities.

“I never ceased to be amazed at all the new great literature being written,” he says, explaining that he was drawn to the subject as a researcher in Cusco, Perú, in 1970. “My interest in cities came from the fact that cities have great art.”

For those of us who think of cities as sprawling spaces of chaos, Cummins’ vision of Latin American cities makes it clear that their origins were the antithesis of disorder. Many of the colonial cities in Latin America were “the Renaissance ideal cities that never gets built in Europe, at least not on this scale,” observes Cummins.

In some countries, the Spaniards found urban spaces, like in Mexico where the Mayans had created big cities and an urban society. In other places, like Peru, there weren’t any cities, so the colonizers made people move into cities, imposing hierarchies and ordering spaces.

“There wouldn’t be Latin America as it is without the drive to build cities,” observes Cummins. “Looking at the ordering of cities dispels many of the precepts about colonialization, that it is simply a violent disordered set of conquistadores.”

“Obviously, some of them were disordered,” he continues. “But the vision was one of order. In fact, they organized these great cities that are today seen as absolutely unmanageable.”

The Spaniards built along the grid system, and ordered systems of space. They looked at the ways buildings faced, taking into account the way the wind blows and distributed the population into what Cummins terms “sociological spaces.”

“But it’s not just about space,” he comments, his words racing as he strings the concepts together. “It’s also the overriding sense of what the Spanish wanted to do with the Americas.”

I listen as he elaborates how the city becomes a memory, an artificial memory, a system of memory that emerges from rhetoric. The Spanish were asking, “How do you construct a city in your mind? How do you indoctrinate people?”

“What kind of elements are important, what aren’t for the social and artistic life of the city?” he asks, pointing out the close relationship in Spanish between terms for architecture and other forms of representation. The frontispiece of a book and the façade of a major structure are called the same thing—a portada. In painting, lienzo is a canvas; in architecture, it’s the face of a building.

I’ve spoken Spanish for several decades now; these words are familiar to me in both their senses, but I had never made the association. Suddenly, over a cup of coffee in a Starbucks, a different and ordered vision of the colonial world becomes vivid to me. I know I have to take Cummins’ course someday.

June Carolyn Erlick is the editor-in-chief of ReVista. She also loves cities—colonial and otherwise.

Related Articles

Bogotá: A City (Almost) Transformed

The sleek red bus zooms out of the station in northern Bogota, a futuristic symbol of an (almost) transformed city. Nearby, thousands of cyclists of all ages enjoy a sunny morning on Latin America’s largest bike-path network.

Editor’s Letter: Cityscapes

I have to confess. I fell passionately, madly, in love at first sight. I was standing on the edge of Bogotá’s National Park, breathing in the rain-washed air laden with the heavy fragrance of eucalyptus trees. I looked up towards the mountains over the red-tiled roofs. And then it happened.

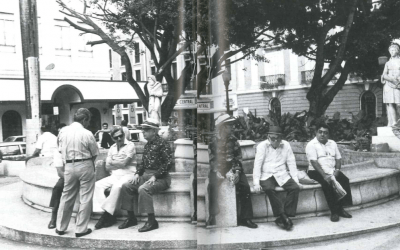

Social Spaces in San Juan

My city, San Juan, is a social city. Its character and virtue are best illustrated and defined by the collective and individual memories of its people and those places where we go to spend time in idleness….