Costa Rica Amidst Climate Change

Navigating the Economic Perils and Opportunities

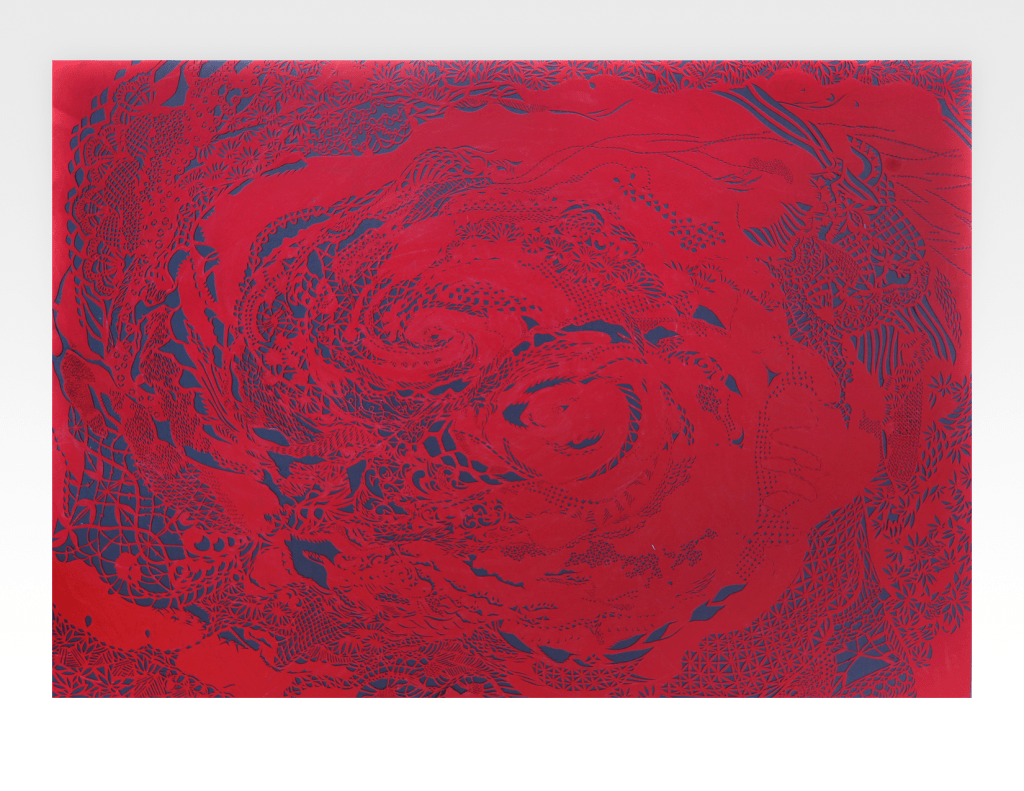

Costa Rica is increasingly vulnerable to extreme weather events like hurricanes. (Hurricane series), 2011, 27.5 in x 39.5 in, cut paper, collage. Artwork by Frances Gallardo www.francesgallardo.com

The devastating Hurricane Otto made landfall in Costa Rica in November 2016, adversely affecting the livelihoods of more than 10,000 people and causing economic damages estimated at least US$185 million. It was the first direct hurricane impact in the Central American country in 165 years. But the winds continued. In October 2017, Tropical Storm Nate struck Costa Rica just days before escalating to a hurricane, becoming the costliest natural disaster in the nation’s history with damages around US$562 million, roughly 1% of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Two years later, Hurricanes Eta and Iota brought significant rainfall, flooding certain areas and considerably displacing affected populations despite not making direct landfall in the country. Costa Rica is increasingly vulnerable to extreme weather events driven by climate change such as droughts, hurricanes, tropical storms, extreme precipitations, and landslides and secular phenomena, such as steady temperature increases, rising sea levels and desertification and biodiversity loss.

Although it is difficult to attribute specific weather events to climate change, what is true is that in Costa Rica, temperatures are increasing, the number of days without precipitation is becoming more prevalent, and, at the same time, short episodes of extreme bursts of rainfall are more and more frequent. Concretely, the average temperature has increased between 0.2°C and 0.3°C per decade since 1970. Precipitation varies a lot from one year to another depending on the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) phenomenon, the cycle of warming and cooling of the tropical Pacific Ocean which has implications for global weather. However, the trends in precipitation suggest that it has slightly increased. Extreme meteorological events—storms and extreme precipitation—have increased in frequency and severity over the last century.

The World Bank’s Climate Change Knowledge Portal provides a projection of Costa Rica’s climate future. The state-of-the-art CMIP6 climate models, on which the most recent assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change(IPCC) bases its analyses, forecast a consistent rise in average monthly temperatures compared to the 1950-2014 period. Projections include an increase of 0.6°C to 1°C by 2030, 1.25°C to 1.75°C by 2050, and 1.5°C to 4°C by the century’s end. The variability in these projections stems from both uncertainty in the future emissions of greenhouse gases and from internal model variability (the bounds I provide come from SSP2-4.5, a moderate emissions scenario, and SSP5-8.5, a high-end of emissions and warming worst-case scenario.)

Annual average precipitation is not expected to change dramatically with climate change. Still, its intra- and interannual variability will rise considerably. These averages subsume regional variability, as rainfall is expected to decrease in the relatively drier regions in the North and Central Pacific and increase in the South Pacific and the Caribbean. Extreme precipitation events are expected to rise. Extreme precipitation events with a 1% probability in a typical year from 1985-2014 are projected to become twice as likely in the upcoming years. The IPCC predicts that hurricanes will affect the area more often, even though they are historically infrequent.

These recent shifts in weather patterns, coupled with the projected impacts of climate change, heighten the country’s vulnerabilities and could lead to significant economic costs. The largest sector in the Costa Rican economy corresponds to services, whereas most of the dynamism and growth is led by subsidiaries of multinational companies in Free Trade Zones that provide professional services to their headquarters or engage in high-value-added manufacturing. Still, the agricultural sector is relevant, especially in employment in the country’s less developed areas. Naturally, agriculture is the sector expected to suffer the most from climate change. More frequent droughts and floods, changing rain patterns, and increasing temperatures will all significantly impact the country’s agricultural sector. Historically relevant staple crops, namely bananas and coffee, will likely suffer a decrease in the area suitable for production, driven mainly by higher temperatures. The implications of climate change are less clear for pineapples, the country’s most important crop and one of its top exports. However, as climate change alters the productivity of distinct crops in Costa Rica, shifting comparative advantage will render new crops more suitable, highlighting the importance of identifying these crops and facilitating their sustainable transition and production.

Bananas will likely suffer a decrease in the area suitable for production, driven mainly by higher temperatures. Photo Credit: Jose Díaz @josediaz2491

Climate change will adversely affect transportation infrastructure in Costa Rica. Road infrastructure in Costa Rica is constantly ranked in the bottom quartile in terms of quality and mean speed scores. Extreme precipitation events, along with landslides, rising temperatures, droughts and sea level rise exacerbate the already low quality of roads, posing significant challenges to Costa Rica’s transportation network. Estimates from the Office of the Comptroller General suggest that the annual costs for repairing and rebuilding public infrastructure due to extreme weather events could range between 1.5% and 2.5% of GDP. This represents a doubling of the historical average costs. Such an increase might strain the country’s public finances, which have been burdened by high deficits since the global financial crisis.

The actual economic costs of frequent road disruptions dwarf the fiscal costs, especially in the Costa Rican context, where there are no alternative means of transportation, and the topography severely constrains the number of routes connecting different economically relevant parts of the country. This is especially true for reaching the Caribbean coast, where the most important maritime port is located. The one major road connected to the capital city, the central economic fulcrum of the country, suffers constant closures due to landslides after periods of considerable rain. For a small exporting country such as Costa Rica, these disruptions can profoundly impact the economy. The inability to transport goods reliably to and from the principal maritime port delays exports and increases costs for businesses and consumers alike.

Lastly, climate change presents important challenges for the energy sector. Costa Rica has produced more than 98% of the electricity it consumes using renewable sources in eight of the last 10 years, mainly hydropower plants, which usually represent more than 70% of production, even though wind power has steadily risen. However, the reliance on hydropower exposes the electric grid to rainfall variability. In 2023, electricity from hydropower constituted about 8% of total production, a figure expected to rise in 2024, moving the country away from its decarbonization goals. The current ENSO phase, associated with drier conditions, complicates matters. However, climate change is likely to cause a significant increase in warm spells, intensifying these challenges, as the declining river flows and increased evaporation reduce the level of the reservoirs.

Projected Change in Precipitation and Temperature in Coasta Rica by 2030, Courtesy of the World Bank

But, at the same time, climate change involves important economic development opportunities for Costa Rica. For instance, its central location, strong economic and political institutions, relatively skilled workforce and strength of its track record in attracting and nurturing foreign investment give Costa Rica a privileged position to benefit from the reallocation of global supply chains in a context where climate change will exacerbate supply chain disruptions. For example, In July 2023, under the auspices of the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022, the U.S. State Department and the Government of Costa Rica established a partnership aimed at enhancing the capabilities of Costa Rica’s semiconductor sector and encouraging investment to diversify the sector’s supply chain. Over the past five years, Costa Rica has further leveraged its proximity to the United States and its stable, democratic environment to promote nearshoring and friendshoring of global supply chains, particularly in the medical devices sector. This strategy aligns with Costa Rica’s longstanding commitment to attracting foreign direct investment, a policy it has vigorously pursued since the 1990s.

Multinational companies aiming to sell in the United States market, yet concerned about disruptions in maritime shipping—whether at sea or due to drought-related issues in the Panama Canal—should consider Costa Rica as a strategic site for positioning high value-added slices of their value chains. To fully leverage this advantage, Costa Rica must enhance its educational investments across all age groups, particularly in STEM fields, and minimize global trading costs by upgrading domestic transportation networks, enhancing port facilities, lowering import tariffs and persistently securing preferential trade agreements with other countries.

Another significant opportunity for the Costa Rican economy comes from its widespread recognition as a global leader in the protection of the environment. Paradoxically, as it sounds, climate change presents another circumstance in which Costa Rica has and needs to keep punching above its weight, leverage its gravitas to enact global change and be a key player in the effort to address climate change. Harnessing its role as a leader in the fight against climate change might bring economic benefits to Costa Rica in the form of increased tourism, investment in green technologies, carbon credits and other payments for environmental services, access to international funding and grants and enhanced global influence and partnerships.

On the Caribbean coast: Harnessing its role as a leader in the fight against climate change might bring economic benefits to Costa Rica in the form of increased tourism. Photo by June Carolyn Erlick

Taking advantage of these potential opportunities while mitigating the costs implied by climate change requires a strategy geared towards a comprehensive adaptation that attempts to reduce both the economic and social impacts of climate change. Adaptation strategies must boost economic activity, protect human, social, and institutional capital and preserve biodiversity and ecosystems.

It is essential to foster resilience through public and private investments. Strategic infrastructure needs to be enhanced and fortified to endure the challenges of increasingly frequent and severe weather events. Additionally, it’s essential to address and remove obstacles that prevent businesses from effectively investing in measures to reduce the vulnerability of their operations to climate change. Public policies should encourage the various economic agents to recognize and manage the risks climate change brings to their actions and activities. This approach should prioritize making actors accountable for their risks rather than promoting private risk-taking by socializing costs.

It is also crucial to recognize that the consequences of climate change will be felt unequally across geographic regions and economic sectors. This will magnify the already significant existing inequalities between the relatively developed and dynamic Valle Central, where the capital city of San José is located, and the rural periphery, especially on the coasts, where the poverty rate is much higher and stagnant.

Indeed, the more pronounced effects of climate change are expected to be felt in the low-lying, developing coasts of Costa Rica, potentially stimulating periods of rural-urban migration, unregulated urban sprawl and slumization akin to the one experienced during the 1980s. In this sense, urban policy is crucial to guarantee the organized growth of the city in such a way that the inflow of people does not concentrate on vulnerable urban areas prone to flooding and landslides, which are cheap and inhabited for a reason. The heterogeneous effects of climate change also represent a political challenge, as the increase in inequality and social fragmentation and the deterioration of institutions could give rise to instability, populist leaders such as the ones that have plagued the region and a weakening of the exemplary Costa Rican democracy.

Recognizing that climate change is here to stay and that it represents a considerable peril for the economy and the well-being of the Costa Ricans, the country has set in motion an ambitious plan, the “Plan Nacional de Adaptación al Cambio Climático” that delineates the governmental adaptation strategy across several themes. There appears to be a commitment between the current party in the government, and most of the opposition parties across the political spectrum, of the importance of successfully adapting to climate change given the imminent risk it represents to Costa Rica.

Certainly, the coming years are pivotal for minimizing Costa Rica’s vulnerability to climate change-induced damages. Immediate action is essential, with public and private sectors needing to invest in adaptation strategies without delay. The economic perils are undoubtedly large, but so are the potential opportunities.

America Free Zone in Heredia, Costa Rica. Photo Credit: America Free Zone

Juanma Castro-Vincenzi is a Costa Rican economist interested in International Trade, Macroeconomics and Environmental Economics. He graduated with a Ph.D in Economics from Princeton University and is currently the inaugural Michael Chae Post-Doctoral Fellow at the Department of Economics of Harvard University. He will join the Department of Economics at the University of Chicago as an Assistant Professor in 2025 after one year as a postdoctoral fellow at the Becker Friedman Institute for Economics.

Related Articles

Homecoming and Public Education: The Cancel Culture (of class time) in Costa Rica

When I returned home on my sabbatical, I couldn’t stop thinking about Svetlana Boym’s extraordinary book, El futuro de la nostalgia.

Crisis of Citizen Insecurity in Costa Rica: A Challenge to the Model of Demilitarized Democracy

I began my political and public service career thirty years ago as Minister of Public Security, the first woman to ever hold that post in my country, Costa Rica.

Editor’s Letter: Is Costa Rica Different?

Is Costa Rica different?