A Review of Crossings: Photographs From the U.S.-Mexico Border

Stepping into the Background of a Magic Realist Novel

Crossings: Photographs From the U.S.-Mexico Border By Alex Webb, Edited by Rebecca Norris Webb Monacelli Press, New York, 2003, 152 pages.

While photographing in areas of the Amazon, Alex Webb felt as if he “had stepped into the setting of a Mario Vargas Llosa or Gabriel García Márquez novel because of the sense of magic realism in the air.” With the exception of his work in Florida, Webb has acknowledged the influence of Latin American Magic Realist literature on all of his work throughout the tropics, including Mexico. In Crossings: Photographs From the U.S.-Mexico Border (2003), an embedded narrative emerges that revolves around three major themes from Latin American Magic Realist Literature: fantastical transformations of the human figure and the found environment; the exploration of socio-political conflicts within societies; and the portrayal of death and spirituality as everyday aspects of life.

The photographer recalls, “I first went to the border in 1975… [M]y initial fascination with the world of border crossers has expanded to include many other kinds of crossings, cultural, economic, spiritual… [T]his U.S.-Mexico borderland has come to fascinate me, almost a third country to itself that is brutally divided—by a river, a fence, a wire—and yet it is also one.”

In Crossings, Webb’s self-described exploration of “emotional and psychological geography” merges pathos, sensuous color, and cultural dissonance. Webb’s work occupies an intersection of literary imagination and the found environment that has challenged the conventions of photojournalism while expanding the genre of photo reportage.

Webb graduated from Harvard College and accepted Charles Harbutt’s invitation to join Magnum Photos in 1974. From 1975 to 1978, inspired by contemporary photographers such as Robert Frank and Henri Cartier-Bresson, Webb photographed the US/Mexican border in black and white. Crossings begins with a sequence of 10 stark and captivating black and white photos, followed by a quote from Capirotada: A Nogales Memoir by Alberto Alvaro Ríos, “The trouble is, we talk about the border…as a place only, instead of an idea as well. But it is both where two countries meet as well as how two countries meet and the handshake is rough.” The book then changes over to color, with images from 1979 to 2001.

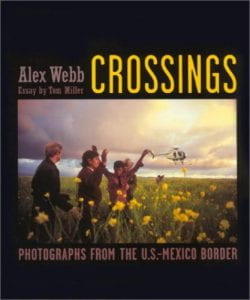

“San Ysidro, California, “Arrest of border Crossers,” 1979. Crossings: Photographs From the U.S.-Mexico Border. by Alex webb. new york: Monacelli Press, 2003. 130. Photo by Alex Webb.

From 1979 to the present, Webb has photographed all of his major books using Kodachrome film, which is known for its hyperbolic translation of colors. His choice of such vibrant color saturation reflects Webb’s longtime interest in Magic Realist literature. Webb first read One Hundred Years of Solitude while studying history and literature at Harvard. One of the more striking images in this novel that is filled with haunting, startling images is that of the enigmatic character Remedios the Beauty floating off into the sky while hanging laundry on a clothesline. This scene belongs to an inverted reality created by the author in which the extraordinary is presented as an ordinary occurrence. In “Boquillas, Coahuila, 1979,” Webb captures a moment that echoes the ascension of Remedios—a boy jumping off a roof appears to grasp a concrete wall in order to prevent himself from floating off into the sky. A red rope leads the eye from the top edge of the frame to an imagined point beyond the photograph toward which the boy might ascend—a visual device that accentuates the boy’s apparent victory over gravity.

Webb’s formal, rectilinear composition and large depth of field creates a visual sense of solidity that “grounds” the image in reality. In contrast, the fantastic pinks and rich tonal range of deep blues create a sense of hyper-reality in which the boy appears to transcend both metaphysical and geographical boundaries. His shadow forms the shape of a cross that perfectly mimics the angle of the Christian cross tilting from the spire of a church in the background. Finally, the child’s levity evokes the soul’s ascent at the time of a person’s death.

This photo appears in Crossings and also begins the sequence of images in Webb’s first book, Hot Light Half-Made Worlds: Photographs from the Tropics (1986). Preceding this image in Hot Light, Webb includes a quote from Carlos Fuentes’ novel The Hydra Head that portrays the “Tropics” as a paradoxical place that combines seductive beauty and devastating terror: “Little by little he began to feel drowsy, lulled by the sweet novelty with which the tropics receives its visitors before unsheathing the claws of its petrified desperation.”

Photography critic Vicki Goldberg thought that she discerned in Hot Light “a kind of brilliant and benign camera colonialism, in which people in underdeveloped countries are appropriated for higher design and effectively ignored.” Goldberg’s political orientation toward Webb’ photography is based on traditional expectations of social documentary photography as a medium that serves as an advocate for social reform or a proponent of the “human condition.”

Webb defended his artistic vision in Hot Light during a presentation of his work at the Fogg Art Museum in 2005: “I think it’s a politically and culturally and historically dangerous book in certain ways in that it ignores all kinds of cultural and historical differences—It was essentially a poetic and atmospheric book,…but I think that this was the right way to initially present this particular obsession that I have.”

While Crossings traverses the intersection between Mexico and the United States, it simultaneously unveils the cultural interactions between the real and imagined worlds that characterize much Latin American Magic Realist literature. In “Outskirts of Tijuana, Mexico, 1995,” Webb’s unique treatment of perspective and depth of field create visual juxtapositions of forms that results in hyperbolic representations of the human figure. In this form of visual alchemy, the individual’s relationship to his environment is transformed to intensify emotional dissonance.

Through Webb’s omnipresent lens, a box of colorful shoes appears as a massive monument towering over miniscule human figures who inch past the construction site of bleak factories where low-paid Mexican workers manufacture goods to export to the United States. The caption for National Geographic’s presentation of this image in the article Tijuana and the Border: Magnet of Opportunity reads: “A portable shoe store lends a touch of flair to a drab dustscape in eastern Tijuana, a growing maquiladora district. The tax-free assembly plants, many foreign owned, employ nearly 700,000 people nationwide and pump life into [local] towns.” But there are other worlds beyond this literal, statistical interpretation of the image. The dream-like, bizarre quality of these shoes resonates with the surrealist idea of found art.

Similar to this use of visual hyperbole by Webb is a magnificent distortion of scale that occurs in One Hundred Years of Solitude, when José Arcadio returns to Macondo as a colossal figure after traveling the world as a gypsy. While his magical increase in size reflects the enormous life experiences he has gained, in “Outskirts of Tijuana” the large appearance of the shoes creates a symbolic decrease of power for the human figures whose visual weight and figurative status is reduced to that of worker bees in relation to the high heels. Webb’s virtuosity for transcending the laws of time and space in his images is matched by his long-term commitment to his projects. Two weeks of field time often results in the exposure of 20,000 frames. Equally impressive is his proximity to his subjects, “I’ve crossed the border illegally a number of times with groups of Mexicans in different places. In each instance, they were caught and I was arrested.”

In “San Ysidro, California, Arrest of Border Crossers, 1979,” which appears as the cover of Crossings, the beauty and terror of the tropics Webb refers to in his The Hydra Head quote is personified and presented as an explicit antagonist. In the buttercup-yellow profusion of flowers is the “sweet novelty,” while the “petrified desperation” is represented by both the stormy skies and the presence of the border patrol and their static helicopter. The sense of “petrified desperation” is palpable in the resigned stance of the border crossers.

While riding with a border patrol truck, Webb saw this arrest unfolding and told the driver to “stop the car!” He explains that this situation was “a gift from the photo gods.” This scene appears to take place somehow outside the normal constraints of time and space, creating the sense that the physical and the metaphysical are co-existent. Webb’s Christ-like figural treatment of the border crossers being arrested and their expressions of quiet acceptance of suffering resonate with Webb’s interest in Catholicism. Webb said that, for him, working in Mexico represented a spiritual and ideological change from the United States. He was, he said, “leaving a capitalist, protestant, individualist country and moving into places where there is a much, much greater sense of mystery.”

In One Hundred Years of Solitude, when Jose Arcadio Buendia dies, there is a spirit of renewal in death that is shown “when the carpenter was taking measurements for the coffin, through the window they saw a light rain of tiny yellow flowers falling.” The spirit of this magical occurrence relates to hyper-real aspects of “Arrest of Border Crossers.” From one perspective, the Mexican men have arrived in an idyllic pastoral landscape dotted with brilliant yellow flowers that evokes the notion that the United States is a land of opportunity. The swollen clouds, which a moment ago might have predicted plenitude, appear ready to burst with a torrential downpour. As they shimmer with a foreboding blend of yellow, purple and blue hues, a visual atmosphere is created that foreshadows the imminent incarceration of the illegal immigrants. In the visual narrative of this image, arrest might be seen as representation of death, where conventional existence and the inner landscape of the mind dissolve into a mythopoeic reality, similar to the consciousness of dreams.

While the power of imaginative literature has affected Webb’s work, photography has also inspired literary works by Magic Realist authors. For example, photographs by James Van Der Zee, Manuel Alvarez Bravo, Henri Cartier-Bresson, and Alfred Eisenstaedt have inspired writings by Toni Morrison, Octavio Paz, Carlos Fuentes, and Gabriel García Márquez respectively. In an interview with Raymond Williams, García Márquez recalls that while writing Autumn of the Patriarch (a book that Webb read) he found a photograph by Alfred Eisenstaed called “Benares, India, 1963,” that “solved my writing the novel.” In the photograph, the fantastical proximity of cows and monkeys climbing elaborate staircases forms a juxtaposition in which the human world has been superceded by the animal world. While García Márquez, borrowing from the photograph, indulges in the sweeping use of hyperbole, he also toys with the reader’s sense of verisimilitude. Further, his personification of the cows serves as an emblem of the “patriarch” of the novel’s corruption, “And one January afternoon we had seen a cow contemplating the sunset from the presidential balcony, just imagine, a cow on the balcony of a nation, what an awful thing.” Williams describes this translation of photographic mise–en–scène as a “poetization of space and writing.”

In Alejo Carpentier’s essay “On the Marvelous Real in America” (1949), he argues that “Marvelous Realism” (a literary label synonymous with Magic Realism) is an amplification of aspects of the imaginative reality present within Latin American culture. Wendy B. Faris and Lois Parkinson Zamora expound on the meaning of Carpentier’s essay, “In Latin America, the fantastic is not to be discovered by subverting or transcending reality with abstract forms and manufactured combinations of images. Rather, the fantastic inheres in the natural and human realities of time and place, where improbable juxtapositions and marvelous mixtures exist by virtue of Latin America’s varied history, geography, demography, and politics—not by manifesto.” Likewise, the fantastical juxtapositions found in Webb’s photographs of the US/Mexican border are not imposed upon his subject—rather, they can be seen as a reflection of the complex social and cultural interaction between these two countries. In relation, Crossings forms the foundation of Webb’s oeuvre—in this assimilation of photojournalism and Latin American Magic Realist Literature, Webb has remained respectful of both traditions.

Spring 2008, Volume VII, Number 3

Kris Snibbe’s book manuscript, “Exploring the Border Between Form and Chaos:” Photojournalism’s Intersection with Latin American Magic Realist Literature in Alex Webb’s Vision of the Tropics” received the Dean’s Prize for Outstanding A.L.M. Thesis in the Humanities from the Harvard Extension School in 2007. Snibbe has completed photographic essays about Mexico City, India, China, and Tibet that revolve around socio-political and religious themes. He has worked as a staff photographer at the Harvard University News Office for 14 years.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter: Puerto Rico

Long, long ago before I ever saw the skyscrapers of Caracas, long before I ever fished for cachama in Barinas with Pedro and Aída, long before I ever dreamed of ReVista, let alone an issue on Venezuela, I heard a song.

God Needs No Passport

For a practicing Buddhist, my first Mass attendance at St. Ambrose two years ago was a memorable event. I had spent the earlier part of the day visiting…

Blood of Brothers: Life and War in Nicaragua

Stephen Kinzer, New York Times Bureau Chief in Nicaragua for most of the war years, pauses in his compelling account of the war and its politics to explain the Socratic method needed to give…