Cuba-U.S. Relations

Détente Before the Third Millennium?

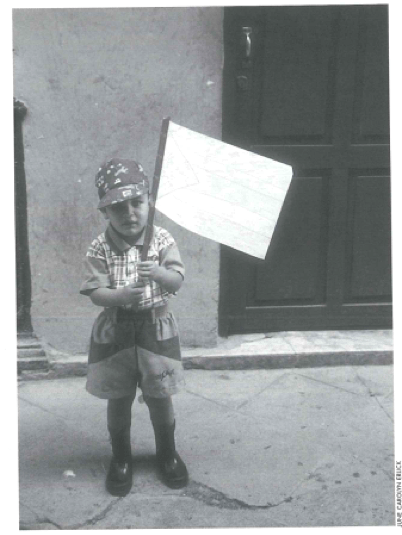

Will this child see normalization of relations in his lifetime?

United States’ policy towards Cuba often appears irrational. Its ups-and-downs reflect the extreme ideological and confrontational relations prevailing between the two countries for more than 40 years. Nevertheless, the balance of power in U.S. politics appears to be shifting away from Cuban American hard-liners with the erosion of conservative support for traditional U.S.-Cuban policy.

A whole new range of players and interest groups have come to influence U.S. policy toward the island. These new players in favor of improved economic and diplomatic relations include non-governmental organizations, humanitarian groups, think tanks, business groups, public health and environmental groups, and a more diverse representation of Cuban Americans.

During non-crisis interludes, these groups often appear to have the upper hand. But when a crisis comes, Cuban foreign policy becomes linked in an artificial manner to domestic electoral politics in Florida and New Jersey, and the political influence of the most fierce lobby. The Cuban American National Foundation has caused a relative alienation of the Cuban issue from U.S. foreign policy objectives, as the recent plight of six-year-old Elián Gonzalez so dramatically illustrates. The case, which seems to be a clear-cut one of migratory policy and parental rights, swiftly became popular fodder for U.S. politicians, both in Congress and on the presidential campaign trail. Yet the debate also underlines that the Cuban American National Foundation is no longer an unchallenged power, as other voices such as the National Council of Churches, opinion polls, much of the U.S. press, and even more moderate Cubans have begun to resonate.

Cutting the Gordian knot with the Miami-based Cuban conservatives requires a new, realistic framework in which to achieve improved relations, as well as political courage. U.S.-Cuba policy remains an anachronistic remnant of the Cold War. The present administration seems to lack the vision and courage to act, and the Cuban American right-wing uses all its political capital to hold the policy of hostility in place.

There is an interesting twist as far as U.S. policy making with respect to Cuba is concerned. It shows an asymmetry in the relevance that each country attaches to the other. While policy-making in Cuba has always taken U.S. politics into serious consideration, the island has not been, in the short or medium term, a political priority for the United States.

For more than 40 years, this fact constrains the debate on U.S. policy towards the island and consequently, a group of hard-liners in Miami with very specific interests in the Cuban issue have traditionally monopolized the discussion, forcing the U.S. policy toward Cuba to be held hostage by domestic factors. Although after the disintegration of the Soviet Union, it was recognized that Cuba was not a threat to U.S. national security, domestic concerns still overshadowed foreign policy.

Two administrations, the former Republican and the current Democratic, have pursued the Cold War of embargo and enmity. However, under the Bush administration, there was a relatively low level of conflict. The U.S. and Cuban governments even managed to sit down at the bargaining table to schedule the withdrawal of South African troops from Namibia and Cuban troops from Angola.

The new context in the 90’s offered an excellent opportunity for a reassessment of U.S. policy towards Cuba. Seemingly, the most controversial aspects in the bilateral relations had been cleared by history, particularly with respect to Central America and Africa.

However, a climate of crisis permeates the decision-making process in the Clinton administration. Policymaking around Cuba was marked by a preference for the “status quo”, a proposed convenience for keeping policy unchanged and acting upon certain circumstances (of crisis?) to ensure the political, economic, and diplomatic isolation of Cuba.

The period’s three major crisis-namely, the 1994 Rafters’ Crisis, the 1996 shoot down of two “Brothers to the Rescue” aircraft by the Cuban government, and the 1999 crisis around the boy Elián González Brotón – are characterized by power vacuums at the highest level of decision making in the U.S., particularly in the National Security Council.

In all three instances, the fragility of the structure of the bilateral relations becomes quite evident. However, other U.S. players are making their voices heard. The National Council of Churches, for instance, played an important role in the Elián González case.

Another example is “USA Engage,” a group of nearly 700 companies, trade associations, and farm organizations, a new movement aimed at eliminating unilateral U.S. economic sanctions against Cuba and elsewhere. Members and supporters include the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the National Association of Manufacturers, Eastman Kodak, General Motors, Goodyear, and Honeywell. Some economists estimate that U.S. trade with the island would jump to $3 billion per year and then soar to $7 billion within a few years if the ban were lifted, according to the study by Kirby Jones and Donna Rich for the Cuban Studies Program of the John Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies.

Speculation about major changes in U.S.-Cuba relations had been sweeping Washington since September 1998 when former Secretaries of State Henry Kissinger and Larry Eagleburger supported an initiative led by republican Senator John W. Warner to create a bipartisan commission to examine U.S. policies toward the island.

The three Cuban American representatives, Ileana Ros-Lehtinen, Lincoln Diáz Balart, and Roberto Menéndez, as well as Senators Robert Torricelli and Bob Graham, immediately began to lobby against the proposed bipartisan Committee. Ros-Lehtinen and Díaz Balart branded it as the “Gore Commission” in an attempt to pressure the possible 2000 presidential candidate.

On January 5, 1999, in a politically cautious move, President Clinton announced “the relaxation of some U.S. restrictions” on Havana, while at the same time rejecting the proposal for a bipartisan commission to review all aspects of U.S. policy toward Cuba.

Most of the announced changes come under Track Two of the 1992 Torricelli Law that allows “people-to-people contacts” as a way of promoting the growth of civil society in Cuba. The basis of “the policy of perpetual hostility”, as phrased by Henry Kissinger, designed to isolate the Cuban government, and the use of the embargo as a key policy element, were combined in a proposal to influence the Cuban society internally to bring about change from inside.

The measures included a study by the United States Information Service of alternative broadcast sites to improve reception of Radio Martí and TV Martí in Cuba and an increase in public diplomacy programs to inform Latin America and the European Community on the reality in Cuba today. Clinton also announced the reestablishment of direct mail service between the United States and Cuba.

Other changes aimed at “facilitating people-to-people contact” were the authorization of the transfer of $300 quarterly by any U.S. citizen to any Cuban family (except for senior-level Cuban government and Communist party officials), in addition to the ongoing remittances from Cuban Americans. Direct flights from New York and Los Angeles for licensed travelers have been added to the existing Miami flights. Food sales to entities independent of the Cuban government by groups such as religious groups or private restaurants could apply for approval on a case-by-case basis.

Overall, the Clinton administration moves were geared toward encouraging expanded educational, cultural, humanitarian, religious, journalistic, and athletic exchange.

This year, the United States will hold presidential elections. Election years have proved that a strengthening of the embargo against Cuba is used to calm down the Cuban American right wing in the swing state of Florida. The political muscles of the new actors advocating for a change of policy are yet to be tried in the policymaking process towards Cuba, and this election year will give us a good idea of their strength.

It is important to bear in mind that the two most significant laws which constitute the cornerstone of U.S. policy toward Cuba were passed during the last two presidential election years: the 1992 Torricelli Act and the 1996 Helms Burton Act.

The Helms-Burton Act labels and defines U.S. policy toward Cuba. It is strict enough to leave very little room for the Administration to apply other policy instruments for the short term.

In early February 1996, several U.S. policy makers involved in Cuban affairs had left their jobs, including Alexander Watson, Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs. This unquestionably created an institutional void right before the February 24, 1996, shooting down of two Brothers to the Rescue Cuban exile aircraft for violation of Cuba’s air space. The incident was the pretext to let the political trend of reinforced hostility prevail. Clinton, not wanting to be perceived as “weak,” signed the Cuban Liberty and Democratic Solidarity Act, better known as the Helms-Burton Act, on March 12, 1996, the same day Republican primaries were held in Florida.

Unlike the 1992 Cuban Democracy Act (Torricelli Law) with its focus on trade, the 1996 legislation targets the financial area to limit Cuba’s necessary re-insertion into the world market. The Act has three major objectives: to tighten the economic siege and hamper the process of economic transformation in Cuba; to render impossible any prospects of improved relations between Cuba and the United States by creating practically insurmountable obstacles to the solution of mutual problems; and to bring Cuba back to the status it had in the early 20th century, when the United States dictated the destiny of the Cuban nation. The essential conflict is sovereignty versus domination.

Paradoxically, U.S. allies reactions to the extraterritorial character of the Helms-Burton Act create favorable conditions for returning Cuba to the U.S. foreign policy agenda instead of relegating it to the domestic agenda. Trade is a top priority in the U.S. foreign policy agenda. There is a pressing lack of consensus in Congress, even among Republicans, on whether international trade should be an instrument of foreign policy. The debate flows mainly between Helms-style isolationists and free trade-oriented conservative Republicans.

After the January 5,1999 measures were announced by President Clinton, a fresh debate about the President’s licensing powers arose. Former Special Assistant to the President and Senior Director for Inter-American Affairs at the National Security Council, James Dobbins, asserted that “Helms-Burton codified the embargo and at the same time, it codified the President’s licensing power. That is, it codified a process by which there was an embargo to which exceptions could be granted on a case-by-case basis by the President.” According to Professor Phil Brenner in Getting Off the Dime: U.S. Policy Toward Cuba, “If this interpretation stands, it opens the door virtually for any license for trade with Cuba that a President would wish to make.”

Almost immediately, the three Cuban American representatives said that they would sue to prevent the President from implementing these changes because they violated the Helms-Burton law.

In Congress, with the rightist conservative movement in major committees and subcommittees, discussion of the Cuban issue has leaned toward enforcing strong measures against the island. In both the Executive and the Congress, a perception prevails that Cuba cannot continue to make its process viable and that, in the short run, changes made on the island will be more in line with foreign policy aims.

Under the Bush administration, Cuba withdrew its troops from Angola.

Another element further complicating bilateral relations is the existence of an articulate, anti-Cuban lobby with some financial power: The Cuban American National Foundation (CAN-F). Despite the 1997 death of its leader Jorge Mas Canosa, the CAN-F still has the ability to sustain pressure within American political circles. Nevertheless, the growing debate over Washington’s policy towards Cuba has now extended beyond the right wing of the Cuban American community. Congressional representatives, business associations, churches, humanitarian groups, academicians and even the Republican Governor of Illinois George Ryan have all underscored the irrational persistence of maintaining a policy that has not brought the expected results, and the imperative need to shift the course prevailing in the non-existing Cuba-U.S. relations for the sake of America’s own political interests.

However, this political craftiness may not be enough to counter the shift in U.S. public opinion, especially within the business community, the Catholic Church, and humanitarian groups. The deep process of transformation of the international system, the new actors advocating for a change of policy towards the island, a more weakened leadership within the CAN-F and demographic changes in the Cuban community in Miami suggest that time may be right for this shift in U.S. public opinion to be translated into a change in policy.

Winter 2000

Soraya M. Castro Marino is a researcher and professor at the University of Havanas Center of Studies on the United States. This article is based on research supported by the Smithsonian Institution by a short-term visitor’s grant in September 1999. She is expected to be a short-term Visiting Fellow at the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies this semester, through the support of the John D. and Catherine I. MacArthur Foundation.

Related Articles

Isabelle DeSisto: Student Perspective

encountered the first obstacle of my trip to the Isla de la Juventud before I even left Havana. Since American credit cards don’t work in Cuba, I couldn’t buy my plane tickets online. But that…

Honoring Humanity: An “Interview” with Richard Mora

Mauricio Barragán Barajas: Why don’t we begin by having you introduce yourself? RM: Alright. I was born in East Los Angeles, and grew up in Cypress Park, a barrio in…

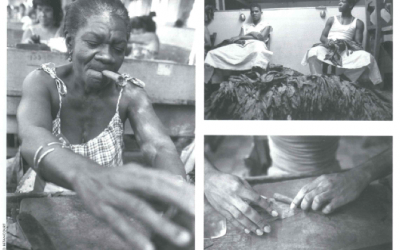

Tobacco and Sugar

“Tobacco and Sugar” is the course that focuses American literatures on the Caribbean, and that acknowledges the unavoidable importance of monocultures for cultural studies. Much of the…