Culinary Collections Recipes and Beyond

Cooking in Argentina

The smells of roast suckling pig “lechón” and spicy enchiladas waft through the book stacks of the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Studies’ Arthur & Elisabeth Schlesinger Library.

That’s only figuratively, of course, since the 16,000 volumes in the fields of cooking, gastronomy, and domestic management are set out staidly in print. Although only a relatively small portion of the library’s collection is devoted to Latin America, the works range from 19th century Mexican cookbooks to the latest tome on low-calorie Latin@ cooking.

For Latin Americans, there’s often the feeling of nostalgia in the culinary collection, with such books as El libro de Doña Petrona: recetas de arte culinaria, a Bible of cooking for any Argentine young woman (and more recently, young men). For historians and other scholars, the books hold forth another way of understanding the past, whether through Ignacio Domech’s 1917 El cocinero americano, a look at New World cooking from the vantage point of Spain, or Elisa Hernández’ 1923 Manual práctico de cocina: para la ciudad y campo, published in Colombia. The books also reflect the booming Latin@ population in the United States, with more recent books such as Miami Spice: the New Florida Cuisine.

Browsing is fun and one must have the time to browse since the books can’t be taken out of the library. There’s an 1856 Manual del cocinero dedicado a las señoritas mexicanas, a very basic cookbook dedicated to the Mexican Miss. Multiculturalism bloomed in cookbooks long before it became a buzzword, and Violeta Autumns’ 1973 A Russian Jew Cooks in Peru features recipes for picante de cuy made with rabbit instead of rodent to keep it kosher and a Peruvian version of borscht beet soup. And then there was The South American Gentleman’s Companion (1931) in two volumes: exotic drinking and exotic cooking.

Dinner is Served, a 1941 book by Luisa Forbes with comical drawings by Brian Fawcett, relates one North American’s experience in Mexico, where she traveled as a child: “I shall never forget my disgust at seeing large fat caterpillars roasted on little sticks and eaten with such relish by white-teethed Kaftirs (in South Africa). But my father very wisely reasoned with me as to their merit and cleanliness, and in Mexico I was one of the few foreigners who enjoyed eating the fried maguey caterpillar.”

As one explores the shelves, one discovers that cookbooks are about point of view, whether it is that of a gentleman prescribing beginning recipes for young ladies or a Russian immigrant trying to figure out how to adapt to her new country, while observing her dietary restrictions.

The Spanish and Latin American collection at the Schlesinger Library expanded greatly with the donation of books from the collection of the late anthropologist Sophie Coe, author of America’s First Cuisine. Coe, an avid book-collector, died of cancer before she could complete her second book The True History of Chocolate, which was completed by her husband, Michael D. Coe, a leading Mesoamerican authority at Yale. Coe’s Spanish- and Portuguese-language books include unusual books on cooking with insects and the myths and rituals of bread, as well as the more standard charity cookbooks and manuals for using leftovers.

Barbara Haber, curator of printed materials at the Schlesinger Library, observes that preparing food was been considered “women’s work” throughout much of history.

“Even feminists were resistant to looking at food,” she said. When the women’s-studies movement got off the ground in the 1970s, cooking was often dismissed as an intellectual topic because one of feminism’s goals was to get women out of the kitchen.

Cookbooks are not merely recipe books; they are rich and informative documents that give invaluable information about the art of cooking and about the lives of those using the books. Cooking and eating have emerged as an area of serious scholarly query, observes Haber, who says she seeks “to make culinary history an academically respectable but not boring subject.”

The Radcliffe collection actually flourished as a result of the disparaging attitude towards cookbooks. In 1961, Harvard University’s Widener Library transferred 1,500 books on domestic science and cookery, dating from 1740 to 1950, to augment the Schlesinger’s 19th century American cookbook and historic etiquette book collection. In the 1960s and 70s, Harvard’s Lamont Library began to collect popular mainstream books. The library decided to give away all the cookbooks it had acquired and a couple of thousand cookbooks ended up at Radcliffe, then an all women’s college. With exceptional gifts flowing into the library in the past 30 years including the collections of Sophie Coe and Julia Child the library has become one of the largest collection of cookbooks in the United States.

When Haber gave a talk on cookbooks at a Toronto conference several years ago, her colleagues accused her of trying to send women back to the kitchen. Food was a reminder of oppression, and those who advocated that the study of food was important were often relegated to the role of a “running dog of the patriarchy.” However, Haber insists, the library collection of cookbooks reflects that women had been a part of public life, even when their voices were silent and only expressed through the preparation of food.

“This too is women’s history,” she stresses, pointing out that cookbooks are social documents, “prescriptive literature” that showed women how to spend their time.

She is no longer alone. The Radcliffe Culinary Friends, affiliated with the library, also provide a forum for discussion about the history of food and culinary investigation through special public programs and First Mondays, a monthly program for food professionals. In addition, this group of food enthusiasts assist the Library in collecting, cataloguing, and preserving the culinary collection.

Maricel Presilla, a culinary historian and author of The Foods of Latin America, tries to get away from her Pan-Latino Hoboken, N.J. restaurant Zafra to attend the Radcliffe events whenever possible. “We are inspired by Haber,” says Presilla, who got her doctorate in medieval history before deciding to go into the food business. “She understands better than anyone about cultura and cocina, about understanding people and societies through food.”

Haber, who is currently finishing a book tentatively entitled, Who Cooked the Last Supper, to be published by Simon and Schuster in 2002, says that food history is now as hot as women’s history.

“I think that once people realized that women’s history is here to stay, people came out of the closet, confessing they love cookbooks,” she says. “Food history has become a whole new field of study. It’s interdisciplinary and multicultural.”

Spring/Summer 2001

June Carolyn Erlick is publications director at the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies. She received a 2001 Fulbright fellowship to conduct research and teach journalism in Guatemala City and is currently writing a biography of Guatemalan journalist Irma Flaquer, who disappeared in 1980.

Related Articles

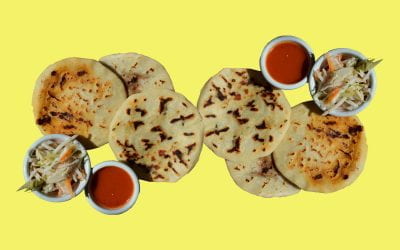

Salvadoran Pupusas

There are different brands of tortilla flour to make the dough. MASECA, which can be found in most large supermarkets in the international section, is one of them but there are others. Follow…

Salpicón Nicaragüense

Nicaraguan salpicón is one of the defining dishes of present-day Nicaraguan cuisine and yet it is unlike anything else that goes by the name of salpicón. Rather, it is an entire menu revolving…

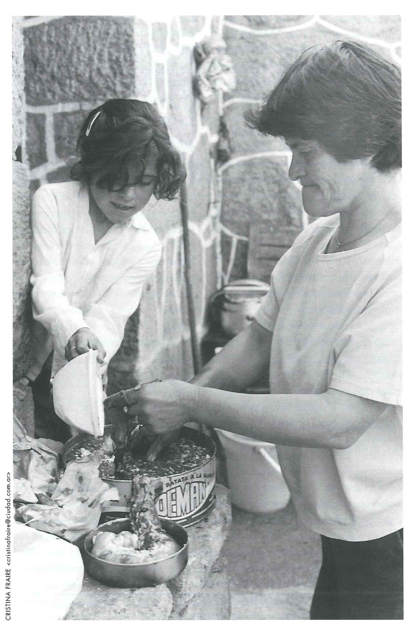

The Lonely Griller

As “a visitor whose days were numbered” in Buenos Aires, Argentina, he tossed aside dietary restrictions to experience the enormous variety of meat dishes, cuts of meat he hadn’t seen…