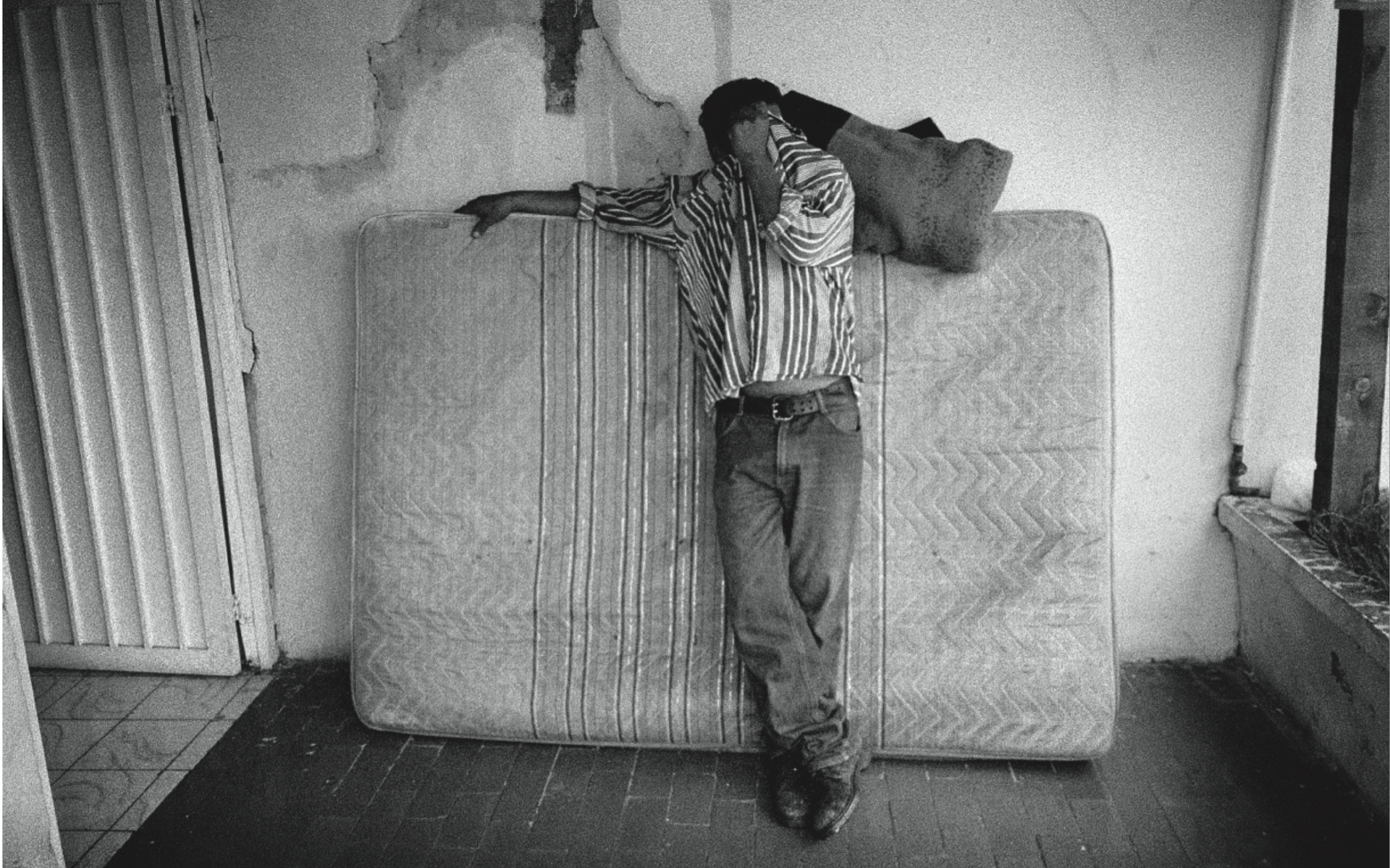

Daily Life on the Border

A Façade of Innocence

CIUDAD JUAREZ. From here, America looks very much like the innocent bystander, dressed in a nice Teflon suit.

Nothing seems to rattle it, not the killings that brought this city to its knees, nor the body count fast reaching 50,000 from the drug violence ravaging my native Mexico, a country that for better or worse shares a 2,000-mile border with its northern neighbor and my adopted homeland, the United States, otherwise known as America.

For border residents like myself, the innocence is but a façade. When I was a young man, my parents owned a restaurant called Freddy’s Café, named after me. It was through that rare opening that I came face-to-face with the issue that now haunts Mexico and my own work as a journalist: organized crime.

Our favorite customers were named Chano, Perica, Pilín, Neto, Memo, Botas, Chapulín and Chiquilín. All nicknames alluding to parrots, grasshoppers, boots and other objects—names to hide identities. No one ever gave their real name. These people would trust us with their mysterious packages overnight or for a few hours. We learned quickly that, on the border, it was best to keep our mouths shut about what we saw and heard. We too acted as unwitting collaborators. We never asked questions. These characters roamed South El Paso Street, hustling and bustling on an avenue that seemed like an extension of Ciudad Juárez, crammed as it was with vendors of cheap goods, T-shirts, lipsticks and other trinkets.

One of our most loyal clients was a tall, attractive woman with long black hair. I knew her only as Paisana (countrywoman), because she came from my native Durango. She was a businesswoman who began her career as a smuggler in El Paso and Juárez. She came from a middle-class family but had traded stability for the raw excitement of the border—which she loved—and where she found it easy to make a fast buck.

One day she brought in several bottles of Malbec wine in sacks. She stood them up on one of our white chairs with light green plastic cushions. As I balanced a heavy bowl of my mother’s caldo de res soup and a plate of red enchiladas stuffed with cheese and topped with cream, I tripped and busted one of Paisana’s bottles. Wine spilled. Amid the shards were thumb-sized balloons stuffed with something white.

Paisana was one of the several so-called fayuqueras, small-time smugglers, who catered to demands on both sides of the border. I knew she moved goods either unavailable in this country or banned by the U.S. government, whether Argentine wines, fruits, cigarettes, Cuban cigars, illegal drugs—anything U.S. clients wanted but couldn’t get legally or cheaper. She carried electronics, TVs and microwaves with her on her trips back to Mexico. That was before NAFTA.

Clients at Freddy’s had left their bags behind before this incident, and sometimes the scent was enough to give away the contents: pot or cash. They’d return for them nervously. But Paisana’s white balloons were something I hadn’t seen before. I had a hunch—after all, I watched “Miami Vice” and heard the talk on the streets. But discretion was a must at my parents’ café, so close to the border and its veil of secrecy and hypocrisy.

“Oops, sorry,” I said. “What is this stuff? Sugar, salt, flour?”

“I don’t really know, but Americans love it,” she responded edgily.

El Neto was the neighborhood drunk, and, like Paisana, a known smuggler of all kinds of contraband—TVs, wines, refrigerators and God knows what else. He was also a notorious lover of women. He loved every mujer who would let him.

Sometimes I listened to him in disbelief, like when he’d start naming the businesses in El Paso that were known money-laundering outlets. Places we knew, places we shopped. Neto was dismayed at my naiveté. We had spent much of our youth in the fields of the San Joaquin Valley so border dynamics were new to us. Look around, he said. Freddy’s is a few blocks from the Chihuahuita neighborhood where La Nacha once lived, the woman who ruled the Juárez smuggling business for nearly 50 years. She shaped the drug trade, taught small-time smugglers like Neto every way to sneak drugs into a country with more than 50 million consumers, stoners and cokeheads who represented billions of dollars. One common game was flooding the border with smugglers while sliming the wheels of some cars with marijuana so that dogs would sniff them out. While border agents were preoccupied with one vehicle, two or three more packed with bricks of weed would pass by with relative ease. “This is the border,” Neto said. “Open your eyes.”

El Neto was always the first one at Freddy’s for breakfast. He staggered in at 6 a.m. just about every morning as my mother was just heating up the ovens. He spent nights loading mysterious bundles from the business next to ours, and occasionally, when he needed extra space, from our own restaurant attic, onto trucks headed for L.A. When the trucks returned, he’d unload the bundles headed for Mexico. I knew that the southbound bundles were filled with used clothes from California. But what the heck were they shipping from Mexico north? One day I asked Neto that question.

He shook his head, pressed his index finger to his mouth and kissed it.

“Freddy, don’t ask questions you don’t want to know the answers to, especially if you want to be a reporter. All legitimate trade,” he said. But he gave me a line in Spanish gently reminding me that curiosity killed the cat. Whatever it was he carried, the demand among millions of Americans was huge and payoff of tens of billions of dollars even greater because those trucks kept on roaring north year round.

Somewhere along the way Mexico, with the latest laws on books but no rule of law to speak of, got a mess on its hands and America once again managed to look the other way.

Spring 2012, Volume XI, Number 3

Alfredo Corchado is the foreign correspondent for The Dallas Morning News, based in Mexico City and working on his first book with the working title, Midnight in Mexico. He’s a 2009 Nieman fellow and a 2010 fellow at the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies.

Related Articles

Transmigration in Mexico

English + Español

En abril del 2010 una delegación oficial de El Salvador encabezada por Francis Hato Hasbún, el Secretario de Asuntos Estratégicos del gobierno del Presidente Mauricio Funes, visitó México…

Organized Crime as Human Rights Issue

English + Español

It was a horrifying scene— 72 people murdered all at once. One survivor bore witness to the massacre. The dead were migrants, mostly Central Americans; 58 men and 14 women trying to…

First Take: Organized Crime in Latin America

English + Español

Dealing with transnational organized crime is now an official part of U.S. security strategy.

A strategy document, issued by the White House in July 2011, speaks of organized crime groups…