Dance Halls

“De donde es usted?” I asked the best Latin dancer I had ever followed around a floor. It was last summer in “centrally isolated,” as the locals say, Ithaca, New York where a friendly gay club goes Latin on Wednesday nights. Once a week we broke up the bucolic boredom that helps to make Cornell University so intellectually restless.

“Sorry, I don’t speak Spanish,” said the dancer.

“Where are you from, then?” I code-switched.

“From Bosnia,” he answered. “My name is Nedim.”

That stopped me short. He had kept me in step through changes in rhythm, but now he lost me. Still grateful for his creative control as a dance partner who knows how to heighten the fun of following with unpredictable segues, even when the moves were familiar, I let my mind wander.

In other clubs in other cities less exotic for Latin music than Ithaca, I had found dancers like Nedim creating urban oases of sociability. A kind of utopian Jetzeit, to use Walter Benjamin’s word, flashes through memories of dancehalls in Monterrey, Montevideo and Montreal, in Santo Domingo and San Juan (where the guy in a baseball cap and too chubby to be Elvis Crespo turned out to be the real thing when he invited us to an outdoor concert the next day), dance floors are the spaces of utopia.

I mean by utopia that everyone fits in, not by looking and acting the same, but by improvising variations on a given theme because dance is a creative art that values difference over conformity. Ernesto Laclau might describe the design of differences on the dance floor as “universal” in the contemporary sense. For the classics, universalism meant conformity so that difference looked like a deviation. But for post-moderns, universality is the space that accommodates differences (a language made up of many styles; a government sustained by divergent views). Its very name suggests how salsa depends on differences of rhythm, origin, mix.

Surely urban dance halls were an inspiration for shaping a better world. Seriously. I heard myself saying so about three years ago after an international meeting to discuss what kind of scholarship and education could promote equitable development worldwide. A day of speeches and debates left us academics clear about obstacles to the good life but mostly clueless about the goal.

“What would a better world look like?” I asked my anthropologist friend Arjun Appadurai at the end of the meeting. I teased him about not being able to say what it was that we were working towards. “Do you want a glimpse of a better world?” I went on. So the intrepid anthropologist let me lead him, loath to allow skepticism to sidetrack us from a field trip into the night of New York.

Half an hour into a taxi ride that brought us only two blocks closer to the river at 10 p.m. that Friday night was enough to make us go native and walk the rest of the way to 57 Street between 10th and 11th Avenues. There stood the Copa Cabana, of glorious memory. This legendary Latin nightclub of the late twentieth century is no more. In its wake, a rhizome of lesser locales now multiplies the points of entry to a worldly utopia in real time and space.

But on that night, the club was still marking its prominent place on the street with a long line of patrons patiently waiting to get inside. The line was something of an antechamber to heaven, like a programmed pause to prepare roughened souls for the refinement on the other side. Detained for the while, we stared at other celebrants who, like us, lagged behind the threshold and inched toward the light and the music.

Dark people, light people, and every shade of African and Asian mixed together sometimes with white, some old ones, more young ones, maybe a mother with young girls or a madam with youngish girls, mixed couples and hybrid singles, glamorous gowns and skintight jeans, the lineup seemed as endless in variety as in length. By the time we passed through the portals and realized that the delay was due to bouncers who frisked the men and scrutinized the women up and down, our participant-observer vision had focused enough to notice the miracle inside: Beyond the floor-to-ceiling fluorescent palm trees and before the stage with a twenty-piece live orchestra that alternated with another to keep the club throbbing through the night, everyone was dancing to the same music.

They danced gracefully, either showy or subtly, and with variations that kept partners attentive to each other. A good move may be part of a familiar repertoire of dance steps and sequences, but the moment and the combination of moves and pauses can take the partner by surprise. A good follower, quick-witted and supple, will absorb the surprise as if she anticipated or even exacted the move from the male lead.

In this art form, as in others, the aesthetic effect is in the small shocks that refresh perception and that the formalists called defamiliarization. This enabling preference for aesthetic play is why choreographed ballroom routines of Latin dancing can seem boring to Latin dancers.

But at the Copa, the rule was to improvise: Improvisation on the dance floor with a range of combinations repeated the spirit of unorthodox mixing and matching of races and regions of the devotees who kept coming to the club. The one feature we all had in common was love for the music and for the combinatory art of movement. It made us almost infinitely interchangeable partners. Not that one dancer was the same as another, but that each would invent moves from the same music in a particular style cribbed and combined from others.

Almost unbelievably, men who were too old and frail to walk up to partners still managed to look fluid on the dance floor. Barely bar-age youths struck classic poses to rhythms that syncopate across generations. At one spot on the floor, a stranger might ask a master to dance (I’ve done it more than once) in order to feel the thrill of expert creative control; at another spot, a man and wife may be doing variations on the steps they have been taking together for decades. The point is that everyone is moved by the music to make signature moves.

Nedim was a master of those moves, I thought, which brought me back to the syncopated conversation.

“Did you learn to dance salsa in Bosnia?” I asked incredulously.

“No, actually, it was in Germany.”

Doris Sommer, professor of Latin American Literature at Harvard University and author of the forthcoming Bilingual Aesthetics: A New Sentimental Education, makes sure that professional meetings end with dances, for obvious ethical and philosophical motivations. Her new project for DRCLAS, to coordinate a network of academics and artists who promote Cultural Agency, can be seen as developing the theme of her piece on Latin dance: universalism as the space for creative differences.

Related Articles

Bogotá: A City (Almost) Transformed

The sleek red bus zooms out of the station in northern Bogota, a futuristic symbol of an (almost) transformed city. Nearby, thousands of cyclists of all ages enjoy a sunny morning on Latin America’s largest bike-path network.

Editor’s Letter: Cityscapes

I have to confess. I fell passionately, madly, in love at first sight. I was standing on the edge of Bogotá’s National Park, breathing in the rain-washed air laden with the heavy fragrance of eucalyptus trees. I looked up towards the mountains over the red-tiled roofs. And then it happened.

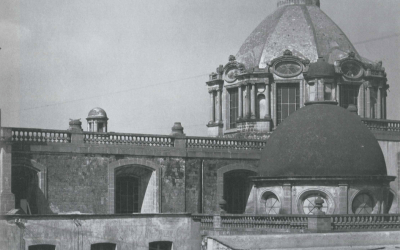

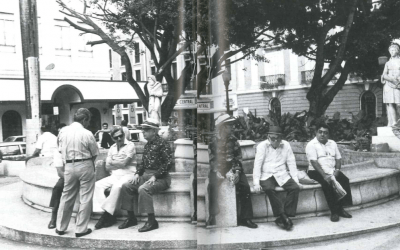

Social Spaces in San Juan

My city, San Juan, is a social city. Its character and virtue are best illustrated and defined by the collective and individual memories of its people and those places where we go to spend time in idleness….