De-encapsulated Bilingual Education in Brazil

Multicultural Breakfasts and Translanguaging Kids

One school in São, Paulo, Brazil—with which co-author Susan Clemensha is very involved— is striving to create multilingual and multicultural contexts for learning, distancing itself from the prescribed curriculum and the traditional separation of languages in bilingual schools.

But before we discuss this example and its unusual practice of Multicultural Breakfasts, let’s take a look at what it means to be bilingual in Brazil and some of the theoretical background framing the teaching at this school.

In Brazil, when we talk about bilingual education, we are talking about two very different realities. Children and youth from minoritarian and underprivileged groups such as immigrant, indigenous or deaf communities make up one group, as Antonieta Megale (2019) points out. The other is children of wealthy people who learn another language to further enhance their privileged participation in society. Brazilians seem to cultivate a notion of monolingualism and, although there are more than 200 languages spoken in the country (Maher, 2013), they seem to be made invisible, which reinforces a denial of cultural diversity in the country (Monte Mór, 2002). Many experts have looked at this situation, including co-author Fernanda Liberali, Antonieta Megale (2019) and Marilda Cavalcanti (1999), among others.

We believe that education should provide expansive new modes of effective participation in society to offer students the chance to increasingly develop forms of insertion in the world and means to transform their mobility. The expansion of mobility should imply the creation of language practices at school which can lead to the reflection of life through a large range of possibilities of understanding concepts, content and knowledge through diverse sources as well as through various semiotic resources and multiple languages.

As part of the Global South, Brazilians must figure out ways of teaching in a multilingual perspective to lessen human suffering, as suggested by Ofelia García (2019). Thus, bilingual education in Brazil should involve breaking with modules imposed by educational parameters or cultural biases which impose a mono-ideology that makes it difficult to move in the direction of a multi/intercultural perspective.

Turning to the challenges presented by globalization, especially in a country with extreme social differences such as Brazil, we must become critically aware of the ways in which schools position themselves regarding local and global issues. When teaching and learning practices enable connections between such issues and the learners’ different realities and needs, change and transformation are more likely to occur.

A Picture of Practice and Research

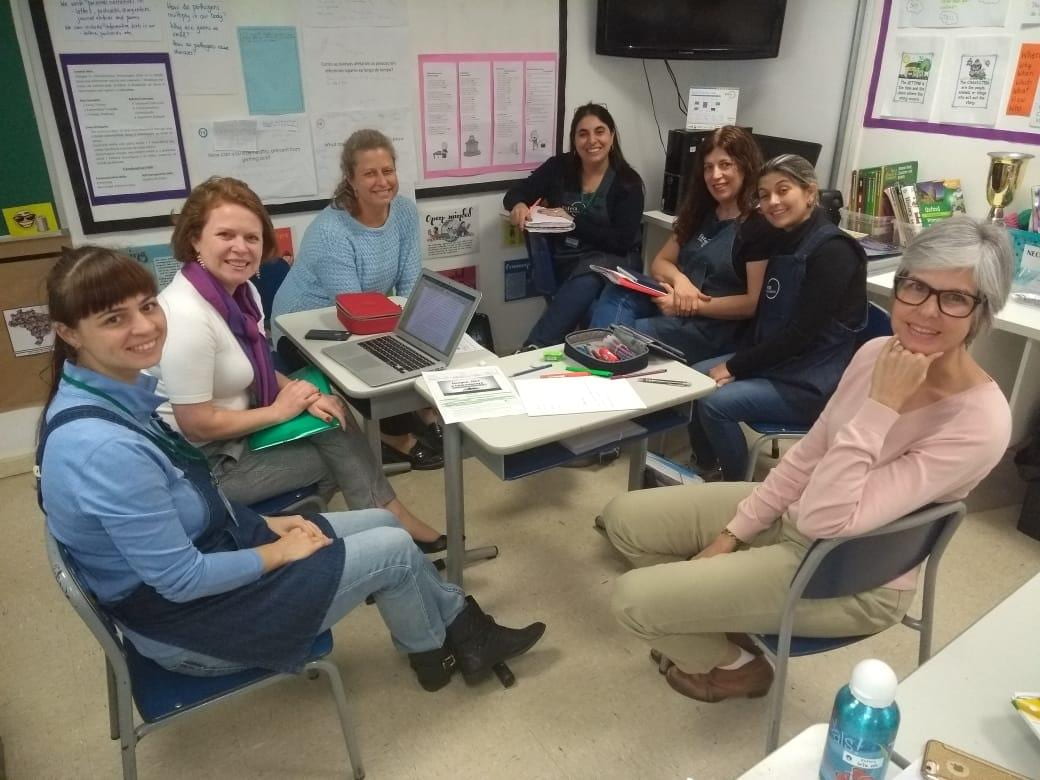

Aiming at showing how some schools in Brazil are striving to implement multicultural and multilingual practices, distancing themselves from the prescribed curriculum and the traditional separation between languages, we will describe an example taken from a research project carried out at Esfera Escola Internacional, a bilingual school in São José dos Campos, São Paulo, Brazil. The methodology was based on critical collaborative research (Magalhães, 2011), in which researchers are included as active participants in the search for shared solutions. Discourse analysis was used to reveal how language was materialized in the participant’s interactions. Although the majority of the students at Esfera are Brazilian, about 15% are from other countries, thus creating a diverse linguistic landscape. Four teachers, coordinators and students made up the research group for the year. Co-author Susan Clemesha, a coordinator at the school at the time, met with the group regularly for collaborative planning.

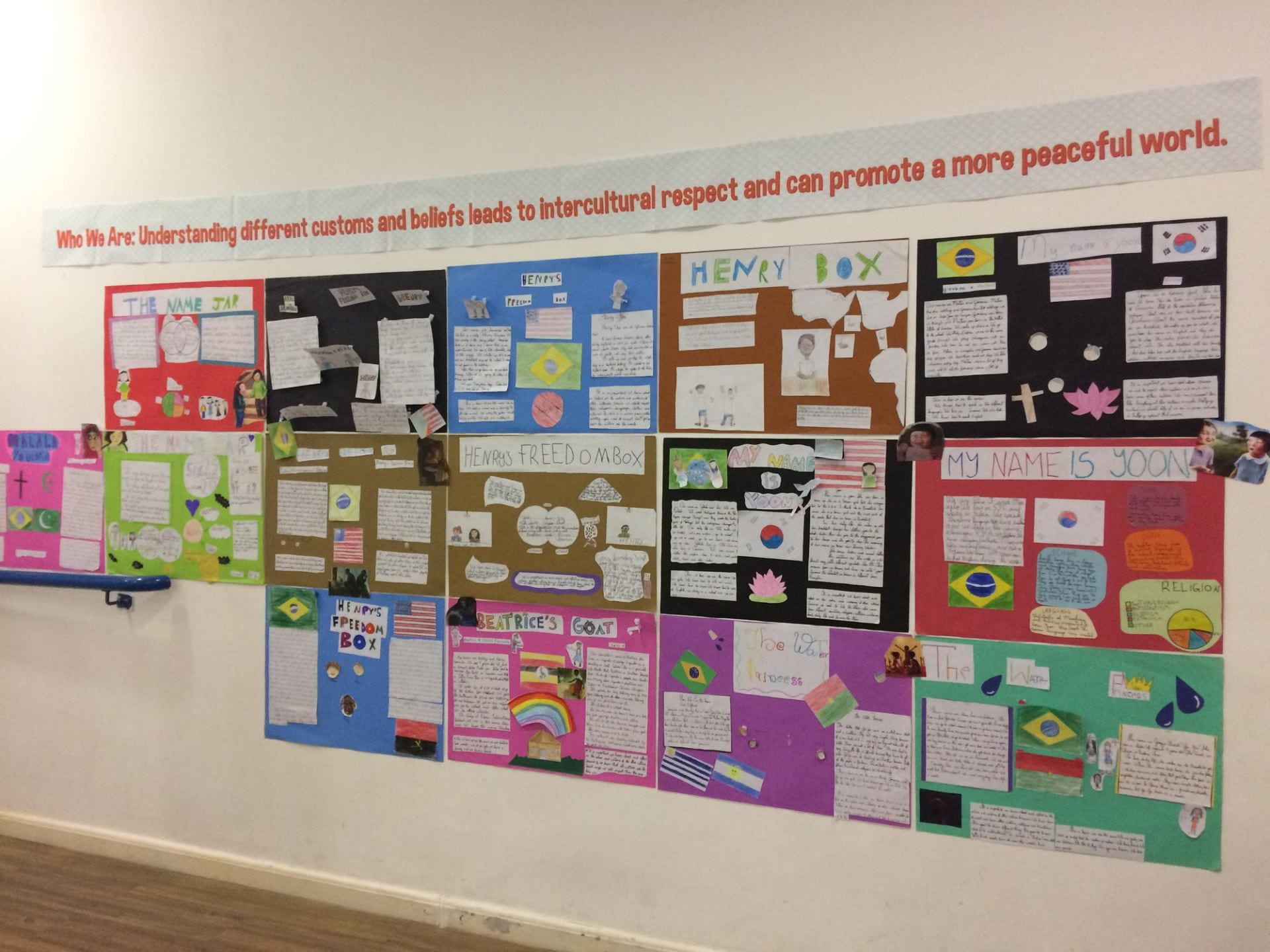

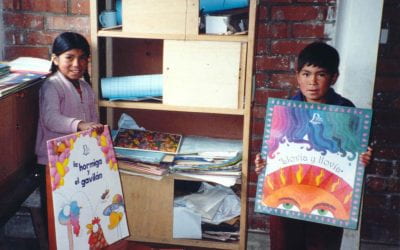

The school follows an inquiry-based curriculum, which is organized through transdisciplinary projects in the primary years. The following excerpts were taken from an interview with two students in fourth grade at a presentation for parents at the end of a project entitled Multicultural Breakfast. To begin their inquiries and provoke questions for exploration, the students read migration stories of children from around the world. They later explored their own family stories of travel and change, and connected them to how the Brazilian people were formed. Making room for further questioning and critical thinking, the students also looked at how migration movements have been affecting people and places in Brazil and the world today. As a performance task, the students invited their parents to breakfast at school, with typical dishes from their countries of origin, and presented their new understandings using different resources and the languages of their preference.

Interview with Two Fourth-grade Students at the Multicultural Breakfast

Lia: We’re going to explain…

Luna: … start asking them which language they prefer, English or Portuguese, and then we are going to start saying what we did in the posters.

Lia: And why.

Susan: Oh, ok. So, what did you do in those posters?

Lia: First we read some books about children from different countries, and we have characters that came from Korea, Burkina Faso, Pakistan, from Africa and USA. This is the context of our unit because it talks about multicultural society.

In the excerpt, a variety of linguistic and multimodal resources were used by Lia and Luna. They looked at each other, listened carefully and pointed to the images on the poster as they expressed themselves. Before answering Susan’s question, Luna clarified that the students would ask parents and visitors about the language of their preference, suggesting the use of translanguaging pedagogy to create opportunities for awareness and collective meaning making.

After her clarification about language choice, Luna answered that the students would explain what they did in the posters, and Lia added that they would also explain why. The de-encapsulated nature of the activity was revealed through the act of contextualization and was supported by the fluid language practices presented in the excerpt.

A Story and a Friend from Korea:

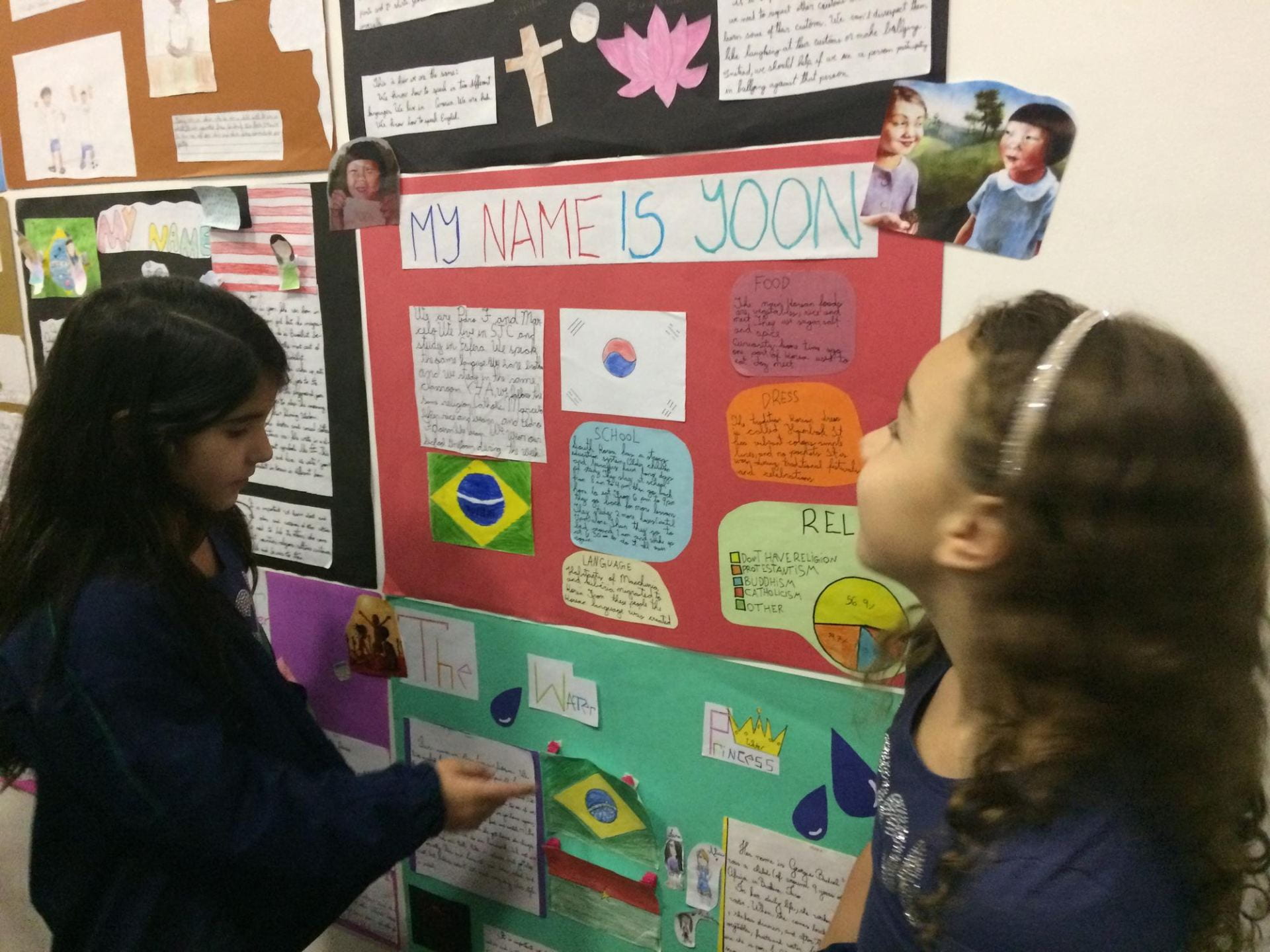

Luna: Here we did the name of the book: My name is Yoon, that is this book…

Susan: Yoon… oh, do you know where she’s from?

Luna: She’s from Korea. This is the flag of Korea and this is our flag. This is her routine: school… school, her language, her dress and her food.

The girls continued to use multimodal language, such as gestures and images from the posters and book cover to support their thoughts. They went on to say that they had a Korean friend in their class who couldn’t understand much Portuguese.

Finding language solutions

Susan: So how do you speak to her if she can’t speak Portuguese?

Lia: We speak in English.

Luna: Because she understands a little bit of English.

Lia: Yes, a little bit of English and a little bit of Portuguese, too.

Susan: And what if she can’t understand either Portuguese or English?

Lia: Then I don’t know…

Luna: We teach her, and sometimes when there is homework and she doesn’t know a word in English or Portuguese, she uses the teacher’s cell phone.

Susan: Ah, what does she do on the phone?

Luna: She researches on the internet.

Lia: She uses the translator and researches in Korean. And then to teach her… we teach her and she learns.

In this part of the interview, Susan purposefully asked the question in Portuguese, as she wanted to understand what language the girls would use in their response. They immediately switched to Portuguese, demonstrating agency regarding language choice. Lia and Luna explained how the children and teachers in fourth grade use their language resources and technology to communicate and make meaning.

The Multicultural Breakfast project broke away from traditional teaching of Brazilian history and created opportunities for contextualization and generalization, while also questioning and considering different perspectives in connection to people’s needs in a globalized world. Extending the dynamic language practices experienced in the project to life outside of school, opportunities were created for students to gain mobility as responsive communicators in their future interactions.

Dynamic Language Practices and De-encapsulation

The Multicultural Breakfast example helps us understand how dynamic language practices and de-encapsulation can support teaching and learning, while also enabling agency and social transformation. Ofelia García (2009, p. 9) asserts that “Bilingual education in the twenty-first century must be reimagined and expanded, as it takes its rightful place as a meaningful way to educate all children and language learners in the world today.” She proposes that the dynamic language practices that take place in the social environment should have a place in bilingual schools, to enhance learning and transform conditions of social injustice.

The complex networks of language practices in which children interact today are no longer supported by linear language instruction. Knowing how to interact dynamically and collaboratively in this new reality is a challenge faced by the new generations and, consequently, a goal for bilingual schools. The traditional notions of languages as distinct and pure systems should be replaced by fluid visions of language for a society in constant movement, as pointed out by Jan Blommaert (2012). When two or more people who don’t share a common language interact, they sometimes rely on language fragments or diverse semiotic resources to communicate. There is a scenario of intense mixture of languages, in which different repertoires are necessary.

Similarly, the dynamic framework (García, 2009) considers language as repertoire, created through the lived experience of language (Busch, 2012; 2015). It pressuposes language not as something one owns, but as something one does. In this perspective, interaction is based on the integration and not separation of languages and resources, an understanding associated with the notion of translanguaging.

In the Multicultural Breakfast excerpts, translanguaging is made visible through the various resources used by Lia and Luna in their interaction with Susan and in the classroom examples they gave regarding the use of technology to assist communication and understanding. Translanguaging is characterized by the interconnected ways in which individuals select and use their language resources from a unitary linguistic repertoire to negotiate and create meaning. Translanguaging can be understood both as a theoretical lens and a pedagogical approach, when teachers intentionally plan for and use fluid language practices in the classroom. In this sense, translanguaging also lends itself to de-encapsulation, according to Sara Vogel and Ofelia García (2017).

The distance between how the curriculum is presented in schools and how it can be explored in real life has motivated studies in the field of de-encapsulation (Liberali et al., 2015, Liberali, 2019b). Traditionally, schoolwork generates individual changes in ways of knowing and being. From the perspective of de-encapsulation, these changes occur collectively and through a variety of cultural artifacts. This process of de-encapsulation allows for school curriculum to be understood as opportunities for problem posing and solving, creating enhanced possibilities for learning outside of the disciplines, the teaching resources and the school itself (Liberali (2019a, 2019b).

De-encapsulation builds on the notion of an ecology of knowledges (Santos, 2006) as central to environments where creativity, innovation and transformation flourish. De-encapsulated practices challenge pre-established truths and value multiculturalism, through an open and continuous process of construction and deconstruction, which results from the interactions between people of different cultural backgrounds. It is not limited to the acceptance of various cultures but is characterized by a movement of appreciation and approximation between them, a disposition which should also be addressed in schools (Freire, 2003). The Multicultural Breakfast project can be viewed through the lens of de-encapsulation, as it aimed to approximate learners to the real world, through events that connected to the reasons for exploration and immigration. While exploring these concepts collaboratively, learners also learned about the formation of the Brazilian people and addressed national standards. De-encapsulation is not only about creating context and connection, but also how different perspectives are valued, in an intentional effort to create meaning and enable agency and transformation.

Dynamic Language Practices

The study presented in this article demonstrates how dynamic language practices were used throughout a de-encapsulated project. Starting from their own family stories of migration and connecting to the books they read, the fourth-grade students explored content, knowledge and skills mandated by the national curriculum in ways which enabled the construction of mobility and lived experience of language, as they questioned their own realities, connected to others and expanded their repertoires critically and collaboratively.

We believe that an attempt to create a Brazilian de-encapsulated and multilingual curriculum (Liberali, 2019a), in line with national regulations regarding language teaching and striving to fulfill the needs for a broader participation of subjects in society is essential.

For references, please refer to: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1oiCQjLwelkXSGezbqOdRZh2-NbaAYikJ/view?usp=sharing

Fall/Winter 2019-2020, Volume XIX, Number 2

Susan Clemesha is the academic head at Sphere International School. She holds a master’s in Applied Linguistics from PUC-SP. Her areas of interest include teacher education, multiculturalism and language studies.

Fernanda Coelho Liberali is a teacher educator, researcher and professor at the PUCSP. Within the framework of Socio-Historical-Cultural Activity Theory, her main research interests are related to teacher education, teaching-learning, multimodal argumentation, multilingualism and bilingual education. She holds a degree in Languages from the UFRJ, a master’s and a doctorate degree in Applied Linguistics from PUCSP, and three postdoctoral degrees from the University of Helsinki, the Berlin Freie Universität and Rutgers University.

Related Articles

Ghosts of Sheridan Circle

Targeted killing of political enemies—assassinations—is thankfully rare in the United States. The most famous such assassination occurred in Washington, DC. And it was committed by a close ally of the United States. In September 1976, Chile’s Pinochet dictatorship…

Bilingualism: Editor’s Letter

It was snowing heavily in New York. It didn’t matter much to me. I was in sunny Santo Domingo with my New York Dominican neighbors on the Christmas break from school. I learned Spanish from them and also at the local bodega, where the shop owner insisted I ask…

Two Wixaritari Communities

English + Español

I first arrived in the wixárika (huichol) zone north of Jalisco, Mexico, in 1998. The communities didn’t have electricity then, and it was really hard to get there because the roads were simply…