Delivering the Data

Women Refugees and Human Rights

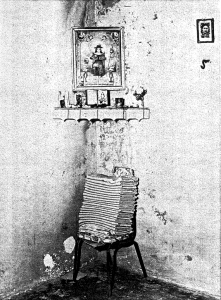

Photo by Dana Salvo.

Marta was 18, living at home in El Salvador, when she dated a man who raped her. She told her father about the rape, and he responded by threatening to kill her for damaging the family’s honor; her mother advised her to marry her rapist. After they married, the husband beat her regularly, breaking bones and leaving scars, and raped her repeatedly, several times in front of their eldest daughter. She never sought assistance from the police, because her husband was a respected member of the community, and his brother was a member of the presidential bodyguard. After he threatened to kill her, she went into hiding, and escaped to the United States. Although Marta’s name is not really Marta, her story is a true one, and one that is typical of a pattern of abuse against many Salvadoran, Latin American, and other women. The stories of the Martas of Latin America are personally powerful narratives. However, I found in my work with the Harvard Law School Clinical Program in conjunction with the non-profit Boston-based Refugee Law Center, Inc., that no one had tried to establish the patterns found in these cases. Each case had to be tackled by itself, often without the benefit of useful precedents.

Judges in most state and federal courts rely on precedents, decisions in earlier cases, to reach their decisions. However, decisions at lower levels of the administrative process in immigration court, under U.S. Justice Department regulations, do not have to be published, in contrast to the requirements for other court decisions. I and several of my colleagues were finding that the results of cases decided had largely been unavailable to the people presenting these cases–immigrants and their lawyers. So Marta’s lawyer might never have found about a similar case in El Salvador or Guatemala or, for that matter, the Congo.

Together with Nancy Kelly, John Willshire Carrera and Margaret Hallissey of the Refugee Law Center, we decided two years ago to begin to record and document the treatment of women refugees seeking asylum from Latin America and the Caribbean in a systematic fashion. With a DRCLAS faculty grant, we developed a database to chronicle these women’s stories, to monitor the progress of the cases, and to examine the decisions in those cases as they are made. Margaret Hallisey, our invaluable collaborator, helped put the database in place. Then we began to network extensively with attorneys around the country and to enter in all significant information. We collected first hand accounts of human rights violations against Latin American women, and of their attempts to escape violence against them because of their gender. The database has become a record of their lives and a primary resource for the identification of patterns and legal arguments which can emerge from such personal narratives.

The sophisticated but user-friendly database also enables us to keep a record of cases decided, published and unpublished, so that the decisions would be easily searchable and usable by all sorts of researchers–academics, attorneys, judges, Immigration and Naturalization officials. Many of the previously unpublished cases (including many of the most interesting ones) wouldn’t be known or available at all if we didn’t do this. This seems especially critical in a developing area of law, like gender-based persecution.

The database also helps systematize published cases, and contains cases, as well as published and unpublished decisions from around the world. Attorneys and researchers can find cases from Canada, Australia, New Zealand, United Kingdom, Sweden, and elsewhere. Asylum cases contain first-hand accounts by the victims of gender violence. We hope that eventually this will be a resource for non-lawyers doing fieldwork research in this area, and provide information to researchers in different disciplines.

The database is now used frequently to assist attorneys representing refugees. There is a critical shortage of lawyers nationwide to assist asylum applicants, and they are all short on resources and time. We felt that a data base would keep track of cases for them and help them network with other lawyers working on similar cases, so that they could share resources and ideas, theories that worked and did not work.

News of our database project has spread to Europe and Australia, so we also are providing information and assistance to attorneys there, networking lawyers working on similar cases and in turn using information provided by them to expand our own database.

While the reasons women flee Latin American countries are many, we specifically focus on tracking reasons related to gender-based persecution.

We have now been able to identify two of the forms of persecution which cause Latin American women to flee: domestic violence and rape by soldiers or the police. As the number of cases in the database increases, we are increasingly able to provide dramatic empirical evidence that these are two major human rights violations against women of this region, and to emphasize further the intersection of asylum law and human rights law. One third of the cases we have involve women fleeing domestic violence.

The second human rights violation cited by Latin American women applying for asylum is rape by military or police. Two thirds of the cases we have worked with involved this kind of persecution. By examining how these cases are handled within the asylum process, we have learned that many judges have been requiring some form of external corroboration, without which the case will not be considered: this is a standard which does not exist in criminal and civil cases decided under our domestic law. After examining this issue in detail, we produced a report on rape as an asylum issue in the United States and in Canada, and submitted it to the UN Human Rights Commission, Special Rapporteur on Violence Against Women. It also has been published in an immigration law publication, and available thereby to practitioners.

We also have produced a legal analysis of domestic violence as a human rights abuse and basis for political asylum which, in collaboration with programs at other law schools and some NGOs, we have submitted as a position paper to the Immigration and Naturalization Service. It also has just been published as an article in a law journal.

Because conditions are changing so rapidly in Latin America, the database is crucial to maintain updated documentation in a consolidated form. Such data are particularly useful to practicing attorneys, but also informs the kind of policy recommendations and position papers to which innovative academic research leads.

With the recent changes in immigration law, the database has become a timely tool to help women immigrants from Latin America at a moment when it is desperately needed because of the extreme backlash against immigrants and the accompanying dramatic decreases in legal and other resources to help them attain justice.

Deborah Anker, coordinator of the Harvard Law School’s Immigration and Refugee Clinic, is a Lecturer on Law at the Harvard Law School. She also assists the Human Rights Program in supervising clinic projects. A co-founder of the private, non-profit, Refugee Law Center, she received a DRCLAS faculty grant to develop the Women’s Asylum Database.

Related Articles

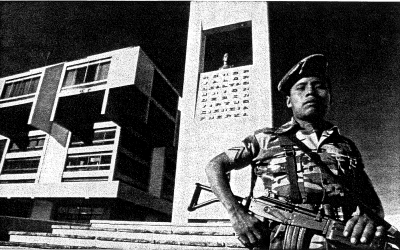

Interviewing Military Officers

We drove up into the residential hills of Villa Hermosa, overlooking the city of Guatemala, searching for the house amongst the many white-stucco, high-walled mansions. I asked the taxi-driver …

Disobedient Autobiographies of Las Desobedientes

From the quasi mythical conquista-age Malinche to contemporary women such as Rigoberta Menchú and Rosario Castellanos, Las Desobedientes restitutes the women of Latin American history …

Black or Mulata?

After my graduation from Yale in the early eighties, I spent several years of research and writing on the novels by Latin American authors. These investigations resulted in my book …