Diadema, SP, Brazil

Housing, Urban Design and Citizenship

Prestigious British magazine The Economist recently featured Brazilian business and finance in a 14-page special report. Under the headline “Brazil takes off,” an article entitled “A better today” cited the city of Diadema as a good example of what Brazil might become in the near future: “If the next ten years see as much social and economic progress as the past ten, Brazil will become a very different place. A good place to see how this might work is Diadema, a formerly rough neighborhood of São Paulo. In 1999 the murder rate there reached 141 per 100,000 people (…) but since then the murder rate has dropped steeply. Earlier this year (…) a six-story shopping mall opened in Diadema. (…) It is a fine place to eat a “pão de queijo” (cheese bread) and reflect on what this spot was like only a short decade ago” (p. 17, The Economist, November 2009).

As mayor of Diadema at the beginning of this decade, I faced a startling high homicide rate, a serious threat for the city’s future. A wide, creative, effective and participatory public security policy reduced the homicide rate from 140 to 20 per 100,000 people in eight years, from 1999 to 2006. In 2007 and 2008 the rate remained nearly the same. In 2009, there was again good news; from January to November the annual rate was 14.3 homicide per 100, 000, tremendous progress.

I could write and discuss the achievements, problems and challenges in public security policy in Diadema here. It would be exciting. Nevertheless, I would like to focus on Diadema’s housing and urban design improvements that have contributed, I am sure, to a very significant reduction in urban violence.

In 1983, when Gilson Menezes, Brazil’s first Workers Party (PT) mayor, took office in Diadema, three out of every ten city dwellers lived in slums (“favelas”). At that time, Diadema had 200,000 residents (now, 400,000). Nearly everything had to be done: 80 percent of the streets needed to be paved and an absolutely precarious health and education system badly needed to be fixed.

In Diadema today, only three out of every hundred dwellers live in favelas. I certainly expect that in the next four or five years, the city might commemorate a landmark: Diadema 2013 or 2014, a city without slums!

Reducing favelas from 30 percent to 3 percent in 25 years is indeed a great achievement. I’ll now try to tell you how this all came about.

1983-1990: THE FIRST 8 YEARS

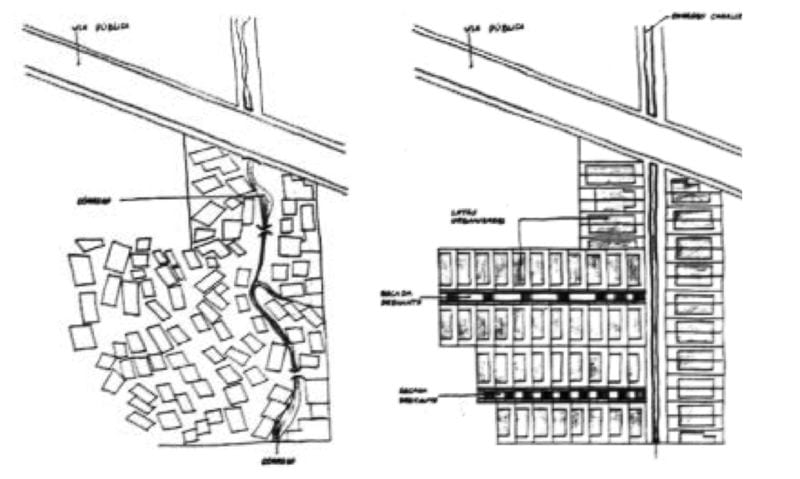

Instead of using the frequent urban design term “slum upgrading,” I prefer the expression “slum reurbanization” and to transform slums in a reurbanized core. As Austrian-born U.S. architect Bernard Rudofsky would say, the slums are urbanism without urbanists. In the early 80s, with very little money for housing policies, we managed to bring together people from the favelas with technical support from City Hall to tackle the problem.

- We can describe the first steps:

- Creation of a City Hall special office team for the reurbanization of favelas

- Motivation of communitarian organization in favelas through dwellers’ committees

- Risk assessment

- Redistricting and relocation of families

- Water and electricity supply

- Sewage collection, stairs and street lights

- Security of land tenure, 90-year concessions.

AFTER THE FIRST STEPS

In the beginning it was very hard. Counting on very little money—from one to two percent of the municipal budget – the City Hall technical and political team started reurbanizing the first slums. Following the steps mentioned above, the first slums to be tackled were those where families did not have to be moved, since we had no financial support to relocate them.

The subsequent relocation of families to permanent lots occurred gradually, based always on solidarity and cooperation among residents. The dweller committees contributed much to the accomplishment of such a hard task – almost all the houses had to be relocated and rebuilt.

Worthy of mention during this period is a municipal land tenure act (Law 819/1985) for those who lived in slums on municipal property. This pioneering initiative, the first of its type in the entire country, served as a means of guaranteeing that dwellers could make home improvements.

After four years of work, only a small number of slums had been reurbanized or were due to begin the process of reurbanization. However, despite some discouraging moments, the process continued.

Once the work is finished, the former slum receives the new name “reurbanized housing nucleus,” and is referred to by that name, even by those who live there. To achieve this status, the area must pass through a process of transforming actions: guarantee of land tenure, with land concessions; infrastructure of public services carried out by the municipality; dweller commitment to building their own houses with technical support and orientation by the municipal housing office.

After all that, the dweller of the former slum, now a reurbanized nucleus, becomes a citizen and owner of a very important distinguishing sign: an address in his city, making it possible for him or her to have access to various urban services for the first time.

1991-1996

During this period, the process became stronger and more productive.

Now more experienced, all the actors, committees and technical support teams could enjoy the advantages of greater financial resources. Thus, the municipal housing policy in Diadema began to carry out the necessary strategic actions to form what would become a real housing policy—a policy through which the reurbanization of slums remained an important action, but never without developing a context to prevent the growth of new subnormal housing settlements.

During this period, there were important initiatives: the creation of the Municipal Fund for Social Interest Housing (Fumapis) in September 1991; the first housing meeting, which brought together dozens of dwellers’ committees and housing movement representatives; the Municipal Council approval of the City Master Plan, which emphasized the creation of Social Interest Special Areas (AEIS) including slums and open areas. Those areas would be reserved for Housing Social Interest Projects. More than 220 acres were designated as AEIS in Diadema in 1994.

At that time, municipal housing policy emphasized following actions:

- Reurbanization of “favelas”

- Municipal land purchases to relocate slum dwellers

- Areas purchased by dwellers’ associations (AEIS)

- New construction projects by state and federal governments.

- Partnership between municipality and social movements for joint projects

- Private investments still in small scale.

1997-2000

That four-year period was the only one in 25 years when the City of Diadema was not governed by PT. It was then that, unfortunately, the Housing Secretariat was closed down and its tasks placed under the jurisdiction of the Public Works Office. It was not by chance that five new big slums rose up in the city at the time.

2001-2008

When PT returned to office, the former policy was put in practice once again. The Housing Secretariat was also restructured. During this period, both the state and federal governments were investing in new social housing units—an important and long-pursued priority for the Diadema municipality.

LATIN AMERICA’S CHALLENGE

As a Loeb fellow at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, I have been doing a lot of interesting reading. New York writer Jane Jacobs’ book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, made a particular impression on me.

I took away some interesting thoughts and questions from her opus:

“Why do some slums stay slums and other slums regenerate themselves even against financial and official opposition?”

“Cities are an immense laboratory of trial and error.”

“The simple needs of automobiles are more easily understood and satisfied than the complex needs of cities…”

Jane Jacobs came to Boston in 1939 and kept in touch with the North End (a well-known Boston neighborhood). When she returned 20 years later in 1959, she wrote:

“When I saw the North End again in 1959, I was amazed at the change”…(in what was) “considered Boston’s worst slum and civic shame.” “Dozens and dozens of building had been rehabilitated,” she observed. “The streets were alive with children playing, people shopping, people strolling, people talking.”

Jacobs declared that she “will be writing about how cities work in real life and then try to learn what principles of planning and what practices in rebuilding can promote social and economic vitality.”

We Latin American dwellers in our own metropoli face this enormous challenge: to provide a better life for millions who also have been arriving in our cities. The reality of Latin America is that poor people have already moved to our cities and settled there. We certainly need new housing and new infrastructure investment, but we should never forget considering what poor people have done their own way, with their own wisdom, to the urbanization of our cities. In many cases this is a good starting point!

Spring | Summer 2010, Volume IX, Number 2

Jose de Filippi is a 2009/2010 Loeb fellow at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. He is a civil engineer and he was, for three terms, mayor of Diadema.

Related Articles

Architecture: Editor’s Letter

For years, readers have been commenting on the printed edition of ReVista: “How beautiful!” Now here’s a website to match, thanks to the efforts of the design firm 2communiqué and Kit Barron of DRCLAS. It’s not only a question of reflecting the aesthetics of the printed…

Working in the Antipodes

I was asked by ReVista to write an article on my own work, specifically about the fact that I do simultaneous work on social housing and high-profile architectural projects, something that is, to…

Three Tall Buildings

I used to hate the three tall towers that thrust against the verdant mountains. I used to think that the red brick towers dug into the landscape, belonging to some other city and some other space, created a scar of modernity…