A Review of Disappeared: A Journalist Silenced

The Perils of Truth and Impartiality During Civil War

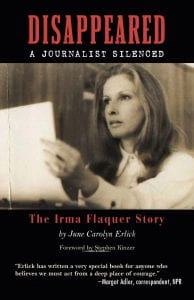

The cover of Disappeared: A Journalist Silenced depicts the Guatemalan journalist Irma Flaquer holding up a page in her left hand as if proofreading. Yet, her eyes are not looking at the paper but upwards. What is she gazing at with such intensity, melancholy and disillusionment? Has she lost faith in herself and her profession? Is she suggesting that we should not look for truth on a printed page or that truth cannot be entrusted to paper? Is this posed picture her ultimate statement about the paradox of practicing political journalism during a civil war?

Irma Flaquer’s professional career began with the writing of the newspaper column ‘Lo que los otros callan’ or ‘What Others Don’t Dare Write.’ A natural talent with only four years of schooling, she was instilled with an ethic of truth-seeking and impartiality by a senior editor. She was a severe but balanced critic of the Guatemalan government, and held no punches to denounce corruption, poverty, and social injustice. Repeatedly, she tried to find a reasonable and pragmatic middle ground in her newspaper articles. She was not against the Guatemalan military but against their abuse of power, not against Cuba’s utopian ideals but against Castro’s sellout to the Soviets and the imprisonment of political opponents. Irma favored gradual social reform to a violent social revolution, and was, according to her biographer June Carolyn Erlick, ‘humanitarian, Christian, vaguely leftist, and highly nationalistic.’ She empathized with all combatants, but never lost sight of the human suffering they inflicted on the poor and downtrodden. In the mid-1960s, Irma Flaquer even tried her hand at repairing Guatemala’s injustices herself by collaborating closely with the Méndez Montenegro government, but became disillusioned by Guatemala’s rapid decline into civil war. She found it increasingly hard to investigate the truth behind many disturbing events, condemning the violence from both sides and pleading for an open dialogue.

Unfortunately, Irma failed to realize that anyone who tries to hold a middle ground in a polarized political situation tends to get criticized from both sides. In this sense, Irma Flaquer resembles Hannah Arendt and Albert Camus. All three were public figures who sought to mediate political violence through dialogue and mutual understanding, and all three were criticized and disparaged by the parties in conflict. Camus considered it his moral duty to infuse some humanity into the French and Arab Algerians during the 1960s independence war, Hannah Arendt tried to be sympathetic to both Jews and Palestinians, while Irma Flaquer sought to reconcile the interests of the military and the guerrillas with those of the Guatemalan people.

What Arendt, Camus, and Flaquer understood was that political conflicts and human suffering are of human making and unmaking. They challenged the logic of violence and appealed to the existence of a common ground, thus undermining the inevitability of a bloody solution to the political and ideological differences. The reconciliatory attitude of Arendt, Camus, and Flaquer placed them above the hostilities and unmasked the oppositional structure as a political construction. All three were condemned, but Irma Flaquer suffered the severest physical consequences.

In 1969, a bomb was placed under Irma’s car, nearly killing her. After a lengthy physical recovery, she returned to political journalism but stayed far from party politics. She stopped believing in national saviors who could single-handedly lift Guatemala out of poverty. Instead, she became infatuated with the 1979 Sandinista Revolution. Here was a progressive reformist movement that occupied a middle ground between capitalism and communism, and tapped into the religiosity of the Nicaraguan people by embracing liberation theology.

Irma Flaquer became increasingly disheartened by the deteriorating political climate in Guatemala—the death squads, disappearances, massacres, impunity, and reign of terror— frustrated by the difficulties to get at the truth, and disillusioned by the lack of impact of her newspaper columns. In a final attempt, she founded in 1980 the Guatemalan Human Rights Commission to document the growing human rights abuses. This effort ended after seven months because of the inability to carry out reliable fact-finding missions. Irma Flaquer also stopped writing her polemic columns, and locked herself into her apartment while continuing to be showered with death threats. Secretly, she joined the FAR (Rebel Armed Forces) and was awaiting orders about where and how to join the armed struggle, when reliable government sources warned her that her life was in grave danger. On the 16th of October 1980, after a rare visit to her grandson, she and her son were ambushed. Her son was wounded mortally and Irma was dragged from the car never to be seen again.

Irma Flaquer’s relentless pursuit of a political dialogue in a hopelessly polarized Guatemalan society, and her professional emphasis on truth and impartiality had imperiled her from all sides. She had become such a political liability that the identity of her assailants remains unclear to this day. This paradox of practicing impartial journalism during a civil war extends itself into this intriguing book by June Erlick. Erlick’s literary talent allows her to maintain a constant suspense that is reminiscent of Francisco Goldman’s brilliant The Long Night of White Chickens. However, unlike with Goldman’s fictional novel, the mysteries in Disappeared: A Journalist Silenced are reflections of Guatemala’s political reality and Irma Flaquer’s complicated life journey. Erlick’s painstaking investigation cannot help but being inconclusive, thus enhancing the credibility of her compelling account. The author suggests that the Guatemalan military were most likely responsible for Irma’s disappearance. She posed a threat if they would fail to stop her from joining the armed struggle in Guatemala, while her acrid pen would do much international damage if they would let her flee abroad. Yet, Irma might just as well have been perceived as a security risk to the guerrillas who feared she might reveal sensitive information under torture.

Irma Flaquer’s persistent attempts to stand above Guatemala’s polarized parties were both edifying and fateful. Journalists stand in the best sense of their profession betwixt and between the world, trying to give equal time to all interlocutors and be evenhanded towards conflicting parties. Irma’s tenacious commitment to truth and impartiality demonstrated the professional limits and personal costs of maintaining such high ethical standard under violent political circumstances. Disappeared: A Journalist Silenced is an enthralling book, highly recommended for all scholars interested in twentieth century Latin America, and a must-read for journalists because of its humbling lessons in professional courage and integrity.

Fall 2004/Winter 2005, Volume III, Number 1

Antonius Robben is a professor of anthropology at Utrecht University, the Netherlands, and a former research fellow at DRCLAS. His most recent book is Political Violence and Trauma in Argentina (2005, U of Pennsylvania Press).

Related Articles

A Review of Authoritarian Consolidation in Times of Crisis: Venezuela under Nicolás Maduro

What happened to the exemplary democracy that characterized Venezuelan democracy from the late 1950s until the turn of the century? Once, Venezuela stood as a model of two-party competition in Latin America, devoted to civil rights and the rule of law. Even Hugo Chávez, Venezuela’s charismatic leader who arguably buried the country’s liberal democracy, sought not to destroy democracy, but to create a new “participatory” democracy, purportedly with even more citizen involvement. Yet, Nicolás Maduro, who assumed the presidency after Chávez’ death in 2013, leads a blatantly authoritarian regime, desperate to retain power.

A Review of Las Luchas por la Memoria: Contra las Violencias en México

Over the past two decades, human rights activists have created multiple sites to mark the death and disappearance of thousands in Mexico’s ongoing “war on drugs.” On January 11, 2014, I observed the creation of a major one in my hometown of Monterrey, Mexico. The date marked the third anniversary of the forced disappearance of college student Roy Rivera Hidalgo. His mother, Leticia Hidalgo, stood alongside other families of the disappeared organized as FUNDENL in a plaza close to the governor’s office. At dusk, she firmly read a collective letter that would become engraved in a plaque on site. “We have decided to take this plaza to remind the government of the urgency with which it should act.”

A Review of A Promising Past: Remodeling Fictions in Parque Central, Caracas

A beacon of modern urban transformation and a laboratory of social reproduction, Parque Central in Caracas is a monumental enclave of 20th-century Venezuelan oil-fueled progress. The monumental urban structure also symbolizes the enduring architectural struggle against entropy, acute in a country where the state routinely neglects its role in providing sustained infrastructural maintenance and social care. Like other ambitious modernizing projects of the Venezuelan petrostate, Parque Central’s modernity was doomed due to the state’s dependence on the global oil economy’s cycles of boom and bust.