Disruption in the Immigrant Experience

Colombian Youth Dance Their Way to Continuity

Imagine you are fifteen years old. As an immigrant who has lived in the United States for a few years, you are still trying to find your place. You decide to join a group that dances the traditional dances of your country. You practice every week on Fridays, when you could be going to the movies or hanging out with your friends. Your goal is to perform in that big annual show a lot of people have told you about. That day has finally arrived and here you are, in the middle of a stage in your costume and make-up, waiting for your turn to dance. The curtain goes up and you find yourself in front of perhaps eight hundred people who are applauding for you, engaged with you, and feeling in awe of your dancing.

This is the experience of young people in the Ballet Juvenil Colombiano (Bajucol), a Boston-based organization that teaches adolescents and young adults to dance and perform Colombian folklore. Founded more than 10 years ago by Northeastern University Business School alumnus Miguel Vargas, Bajucol’s mission has been to keep young people off the streets, to provide learning opportunities to those who feel passionate about dancing and to change Colombia’s bad reputation associated with the drug-trade and violence. As a Colombian and a developmental psychologist, I became interested in Bajucol as an intervention that fosters a positive connection between Colombian youth and its cultural heritage, rather than focus on negative aspects of the young people’s lives. The predominantly Colombian organization also attracted me because of the incredible commitment to the group by youth, their parents and the director.

Bajucol was established in the context of Colombia’s worsening economic and political conditions, which caused immigration to spiral. Colombians are now the largest South American group in the United States, and the fifth biggest Latino group in Massachusetts. Colombian migration specialist Luis Eduardo Guarnizo has pointed out that Colombians have a stronger resemblance to the U.S. mainstream than other Latino groups in terms of sex composition, race, age, and levels of education. Still, distrust within the Colombian immigrant community has been rampant, attributed mostly to the drug-related stigma, to Colombians’ social organization along class and regional lines, and to their predominant urban origin. Colombian organizations in the United States tend to be short-lived, contributing to the widespread perception that Colombians are not united and do not collaborate among themselves.

What does this all mean for youth and children? For children, the immigration process can be a very stressful experience, often including loss and grief, family separations and war-related trauma. These factors can be worsened by poverty, poor schooling or high levels of violence in the receiving context—their U.S. neighborhoods. Still, despite such challenges, many immigrant children will develop positively, though young Colombians are at risk of internalizing images about themselves consistent with negative images that both Colombians and non-Colombians may hold of them. Bajucol is a good example of how dance programs focused on youth culture can have strong potential to promote positive adaptation by easing the transition to the new country. Groups such as Bajucol provide a sense of continuity that is threatened by the migration process. They offer the means to explore and positively connect with youth’s cultural heritage, as well as to create a sense of agency in response to negative stereotyping.

MAINTENANCE AND CONTINUITY OF COLOMBIAN CULTURE

Many Bajucol participants told me they had been unhappy in Boston and wanted to return to Colombia. This idea of returning was more a wish than a realistic expectation, because their parents had made enormous sacrifices to come to the United States and did not want their children returning. In fact, parents’ desires to help their children adapt to the United States while maintaining connections with their own culture were major incentives for encouraging younger and older children alike to get involved in Bajucol. Hence maintaining Colombian culture through Bajucol involved keeping a connection alive and providing some continuity in relation to activities and relationships severed by the process of migration. Some youth described how both Colombian peers and dances helped them find “a little of Colombia” in them that they valued and missed.

Let’s us examine Sonia’s case (all the names here are pseudonyms used to protect the identity of youth). Initially she wanted to return to Colombia because she was unhappy in the United States. She was 16 years old when she came against her wishes, thinking that she would stay for only a year and then go back. Active in extracurricular activities back in Colombia, she felt disoriented and lonely in the United States. Her involvement in Bajucol gradually allowed her to feel at home by reconstructing some of the things that used to define her sense of self in Colombia. In her words:

Kids in Bajucol taught me a lot, not only as dancing partners, but as people…. They were the ones who taught me to love being here, to be able to have a life again here; not feeling like ‘okay, when am I going to return to Colombia?’… When I came, I arrived to a world where people told me ‘you come here just to work and save money.’ And the kids taught me that there was more, there were movies, there were parks to enjoy, that there was a school where you could have cultural activities. I mean, I said ‘okay, I can do the same things here that I used to do there [in Colombia].’

This sense of continuity fostered by Bajucol counters the disruption caused by migration and allows youth adaptation here not to be entirely focused on the experience of being an immigrant. For Sonia, thinking that the only thing she was expected to do was work and save money was rather sad. Those feelings are especially true for youth whose families experience financial struggles, working several shifts to make ends meet, or having difficulties themselves in the adaptation process. Young people, especially girls, had to help their parents, which left little time to engage in positive activities. This feeling of continuity could serve as a protective factor against depression or disengagement, often experienced by immigrant youth.

This was clear in Lina’s case. She arrived here as a teenager. Her adaptation to the United States was so difficult to the point that she described it as “traumatizing.” Her limited language ability made her feel “mute,” and thus kept her from making friends at an age when friends are very important. When she started learning English, her frustration deepened because she had to babysit her newborn brother after school, precisely when most activities for youth her age were taking place. When Lina found out about Bajucol she thought it would be a perfect opportunity to recover the experiences that used to define her in Colombia—having great friends and being very active. Linas’s mom and stepfather eventually decided to change their working schedules so Lina could participate in the group.

It’s funny, at the time I got involved in Bajucol, I was thinking about going back to Colombia. I was fed up…I couldn’t do what people my age did… I was so depressed for not having friends and school was boring, so I thought [joining Bajucol] would be a good way to go back to the way I used to be: concentrating in music, having friends with similar culture and beliefs as mine, or at least from the same country. That really caught my attention. Plus I always loved participating in activities, so I joined in and I loved it. (Lina)

Thus Bajucol was crucial in her adaptation, providing encouragement, guidance and a familiar environment to make friends. That Bajucol was mostly an all-Colombian and mainly an immigrant group helped newcomers make the transition into a new context. Older members in Bajucol served as cultural translators that connected newcomers with different resources to ease adaptation, giving, for example, information about college applications or scholarships. And the fact that it was an all-Colombian group led by a responsible adult helped parents such as Lina’s decide to support their children’s involvement. Youngsters told how parents were proud of them for demonstrating the positive side of Colombia and participating in productive activities, rather than being out on the streets engaging in risky behavior.

Many Bajucol members had lived much of their lives in Colombia, and yet Bajucol provides them with new information about Colombian folklore such as traditions, costumes, music, history and dances. Through organizations such as Bajucol, cultural values are transmitted about what it means to be Colombian —celebrating Colombians holidays together or supporting parental expectations about appropriate behavior. In immigrant families, conflicts arising from parents’ fear that their children will become Americanized and thus alienated from the older generation are not uncommon. Thus for both children and parents, Bajucol became a critical place where the disruption of migration was mitigated and where more consistent messages were being communicated.

Through its activities Bajucol also allowed long-term Colombian immigrants to reconnect and maintain ties to things that they were once exposed to and were now far from. Financial constraints or immigration documentation difficulties prevent many Colombians from returning to Colombia for long periods of time, sometimes even decades. Understandably, they long for familiar places, music and cultural activities. Oscar, another Bajucol member, told me about the importance of maintaining ties to the culture through dance:

We are in a foreign country and people tend to lose a lot of things from their home country. Culture is something we have to maintain, including the [Spanish] language and the customs. Here, it is inevitable to lose a lot of things, you cannot do the things you used to do there… so we were trying to maintain that. When people saw us performing aSanjuanero or a Cumbia it gave them the shivers, because it had been a long time since they saw them last, not even on T.V.

The Colombian community needs Bajucol as much as Bajucol members need that audience. Developmental psychologist Michael Nakkula argues that a reciprocal transformation develops between young people and adults in the context of youth interventions. In the transformation process, each person’s histories, prejudices, hopes and fears intersect, bringing about self-reflection and understanding in both parties. I found that the same phenomenon takes place in both the performances and overall participation in Bajucol: the histories and preconceptions of both dancers and audience come together. The intensity of the experience is heightened through the culturally specific content of the performance—Colombian dances and folklore. The audience “gets the shivers” and cries, and youths reflect on who they are, becoming more proud of their own culture.

Participation in Bajucol leads to self-understanding and to a construction of an identity, a task that is critical during adolescence. In her 1990 book Self and Identity Development, psychologist Susan Harter observes that youth are in search of self, and because “the self is a social construction,” feedback, values, and directives from parents, peers and friends become a source of a realistic self-concept. Youth co-construct their identity in the interaction with Bajucol peers and audience. Immigration scholar Carola Suárez-Orozco coined the term social mirroring to refer to the way in which adults, peers, and the media become the mirrors of youth; positive and negative images can lead to a sense of self-worth or the lack thereof, respectively. In my work, I’ve discovered that Bajucol has been an important and a positive socializing context for identity development. One group participant, César, tells of being very excited about performances because of the applause, noise and camera flashes. He adds:

There were times when, for example, we went to a festival in Lawrence, oh, I’m never going to forget this! And over there it was the first time we danced the salsa. And I remember that that day the people were even asking for our autographs… Can you imagine? That motivates you to keep on going.

Audience reaction embodies recognition by the other, the mirror. Thus, youth recognize themselves positively beyond the more personal context of relationships. This process can be both personal and impersonal: impersonal, in that the audience does not necessarily know the performers—their histories, their personalities, their unique selves; and personal, in that the applause is aimed at the performers directly, at their dances, their movements, their expressions. The impersonal aspect of performance can be especially positive for youth who have a negative self-image of themselves in other areas. For a youngster who is known at school for being problematic or a bad student, having a context of positive identification detached from the school context can be very positive. In Bajucol, both the personal and the impersonal aspects of performance make it a place for potential positive identification.

DANCES OF RESISTANCE

Many performances also took place before non-Colombian audiences in venues such as schools, universities and the annual show. Thus, Bajucol becomes a vehicle of cultural resistance, and, more specifically, agency, in the sense that they are contesting negative Colombian stereotypes and stigma through a positive cultural representation of Colombia.

This seems a better expression of resistance than many common forms of youth resistance, such as school disengagement and risk-taking behavior. This can be summarized in the expression “Why would I act out when I can act on?” (In this sense, “act on” means to perform.) According to anthropologist Jean Comaroff, cultural resistance is usually complex, because in the social action there is a dynamic tension between transforming and reproducing the social order.

The power of Bajucol in countering negative cultural stereotypes relies then on two aspects: one, preserving and enhancing the individual’s positive self-concept by providing positive cultural attributes to be proud of; and second, promoting a sense of agency through which youth feel they are representing culture as well as creating new representations of what Colombia is about to those who are familiar only with its negative aspects. Furthermore, providing a context in which youth can identify and celebrate positive cultural traditions is important, especially in contexts where their traditions are not recognized or represented, as for example in schools or neighborhoods.

Given that interventions like Bajucol are not uncommon (there are many examples of artistic, athletic, or educational groups that share a common ethnic heritage), I hope this article can help those interested in programs that reach ethnic minorities and immigrant youth in meaningful ways.

Claudia G. Pineda, Ed. D. recently received her doctorate from the Harvard Graduate School of Education in Human Development and Psychology. Currently, she is a Visiting Scholar at the Latin American Studies Program at Cornell University. This article is based on her dissertation work conducted between 2004 and 2005. E-mail Claudia_Pineda@post.harvard.edu If you want further information on Bajucol, contact Bajucol1@aol.com or visit its website at https://www.bajucodancestudio.com

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter: Dance!

We were little black cats with white whiskers and long tails. One musical number from my one and only dance performance—in the fifth grade—has always stuck in my head. It was called “Hernando’s Hideaway,” a rhythm I was told was a tango from a faraway place called Argentina.

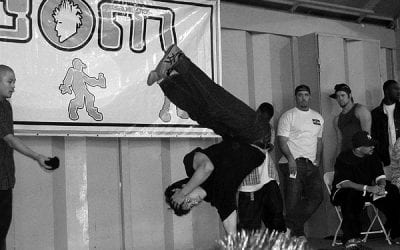

Brazilian Breakdancing

When you think about breakdancing, images of kids popping, locking, and wind-milling, hand- standing, shoulder-rolling, and hand-jumping, might come to mind. And those kids might be city kids dancing in vacant lots and playgrounds. Now, New England kids of all classes and cultures are getting a chance to practice break-dancing in their school gyms and then go learn about it in a teaching unit designed by Veronica …

Dance Revolution: Creating Global Citizens in the Favelas of Rio

Yolanda Demétrio stares out the window of our public bus in Rio de Janeiro, on our way to visit her dance colleagues at Rio’s avant-garde cultural center, Fundição Progresso. Yolanda is a 37-year-old dance teacher, homeowner, social entrepreneur and former favela (Brazilian urban shantytown) resident. She is the founder and director of Espaço Aberto (Open Space), an organization through which Yolanda has nearly …