Drizzling Labyrinths of Beautiful Villages and Sublime Megalopolis

“Parque Ibirapuera” by Rodrigo_Soldon is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

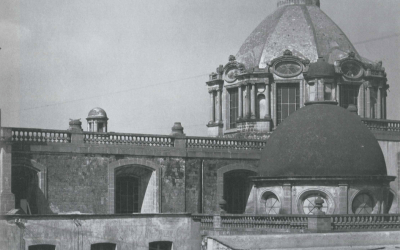

As the privileged scenario for the splendors and pitfalls of modernity, the city has been the depository of its most common and popular metaphors. Whether described as a reflection of an orderly and pragmatic rationale, or as a crowded space were individuals strive to remain in possession of their identity, we have become used to think about cities on analogies that not only reveal our appreciation or discredit of the modern project, but that underscore the impossibility of a straight, univocal definition of a ever changing, omnivorous and almost amorphous space. At once a living organism, a grided mythological figure, a bright luminous force, the tangible materialization of a dogma or an impossible geometrical figure, not other metaphor has been more overused for describing the city since the late nineteen century than that of a “labyrinth” or a “maze.”

A tortuous network of paths and corridors aimed to disorient the unlucky wonderer who dares to enter in, the labyrinth as a token image of the city has persisted over the decades not only because its share it most evident characteristic –tangible constructions, architectonic designs—but because it seems to convey the same level of attraction and fear that the modern city exhales. Allegedly, in some level, both city and labyrinth produce the same psychological state: confusion. In that way, and just as Walter Benjamin hints in his “A Berlin Chronicle”, the modern city dweller becomes a Theseus, while the streets of the city echo the walls of the dreaded Minoian labyrinth.

Perhaps the clearest example of how entrenched and present is such metaphor in the cultural and artistic imagination in Latin America and other regions was the embattled 25th Bienal de São Paulo (celebrated between March and June, 2002). The theme of the gathering was, precisely, “Iconografias metropolitanas” (City Iconographies), for which the organizers selected eleven cities (Berlin, London, Johannesburg, Istanbul, Beijing, Tokyo, Sydney, etc) and commissioned a renowned curator in each of them to select a group of representative artists whose work dealt with the city. An imaginary twelfth city –“A Cidade Prometida”–was “constructed” by the proposals of a group of selected Brazilian and foreign artists intended “to become a sketch map of a necessary Utopia” (in words of Carlos Bratke, the Bienal’s president). Latin American cities were “represented” by Caracas and São Paulo itself by a contingent of established and up and coming artists of talent, but some other Cuban, Argentine and Peruvian artists were also exhibited across the many small parallel exhibits the Bienal shelters under its umbrella.

The result was a large, eclectic and interesting collection of different artistic caliber, but it turned out to be as well an exercise on predictability: inevitably, artists after artist, city after city, the image of the “labyrinth” and its conspicuous effects of confusion and disorientation emerged as the proposed aesthetical effects. Indeed, few artists, perhaps the most innovative, escaped the facilism of appealing to a category that seems to belong more to the archetypical avant-garde of the early twentieth century than to the disjointed, disarming, tensioned and heterogeneous landscapes of a post-modern megalopolis. And considering the fact the Modernist pavilions where the Biennal was hosted is a maze in themselves which are, in turn, situated in the arguable center –the Parque de Ibirapuera–of city presented in the same exhibit as labyrinthic as no other one in the southern hemisphere, the number of reflecting mirrors carrying the same image seemed way too redundant, too gratuitous.

Nevertheless, the obvious redundancy of the Bienal presents us with an important question: if not labyrinth, what else can a city such as Sao Paulo, with it’s almost 18 million inhabitants, resemble? What is the other sets of metaphors that we need to use in order to start making sense of the vastness of Mexico City, or of the indiscriminate violence that seems to engulf every inhabitant of Lima and Bogota?

A possible answer may be encountered, again, in the arts, only that this time in the literary medium.

Jose Luis Falconi is a doctoral student in Romance Languages and Literatures at Harvard University.

Related Articles

Bogotá: A City (Almost) Transformed

The sleek red bus zooms out of the station in northern Bogota, a futuristic symbol of an (almost) transformed city. Nearby, thousands of cyclists of all ages enjoy a sunny morning on Latin America’s largest bike-path network.

Editor’s Letter: Cityscapes

I have to confess. I fell passionately, madly, in love at first sight. I was standing on the edge of Bogotá’s National Park, breathing in the rain-washed air laden with the heavy fragrance of eucalyptus trees. I looked up towards the mountains over the red-tiled roofs. And then it happened.

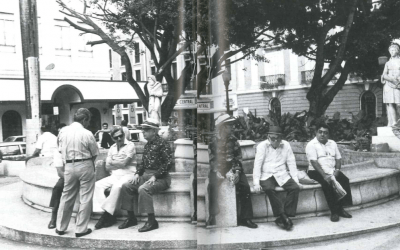

Social Spaces in San Juan

My city, San Juan, is a social city. Its character and virtue are best illustrated and defined by the collective and individual memories of its people and those places where we go to spend time in idleness….