The Tragic Saga of the Scorpion Flower

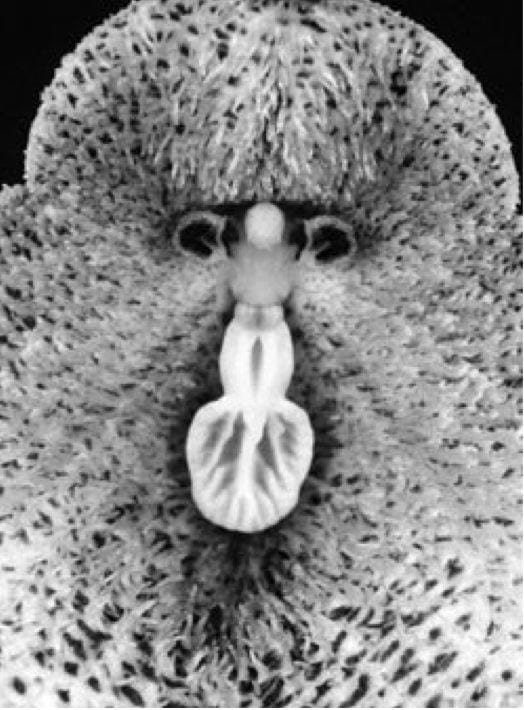

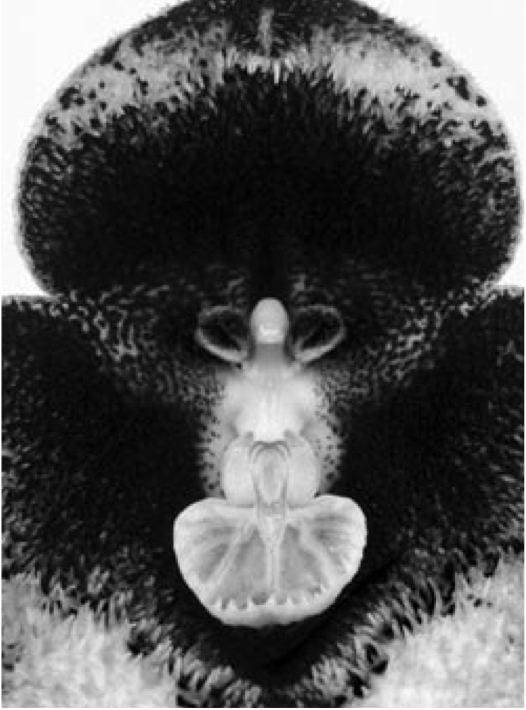

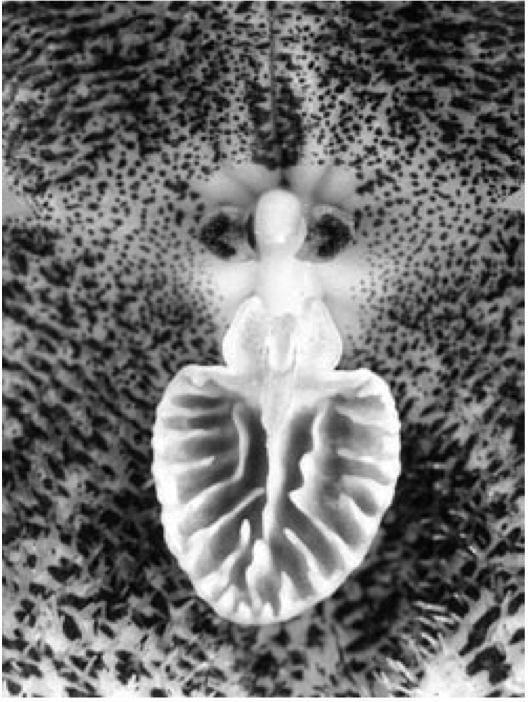

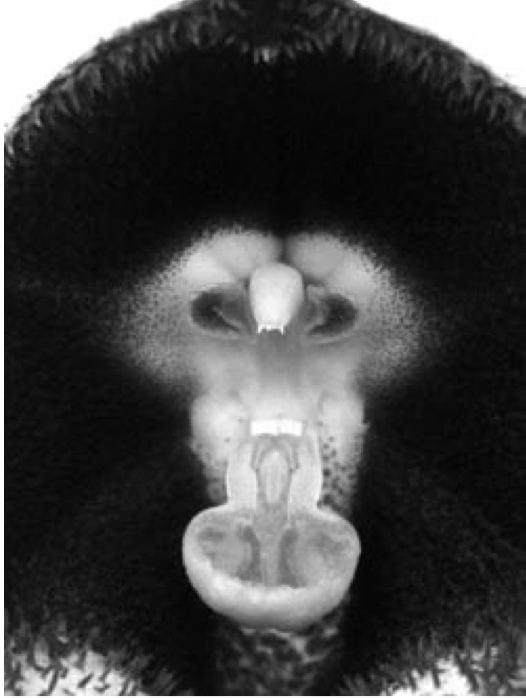

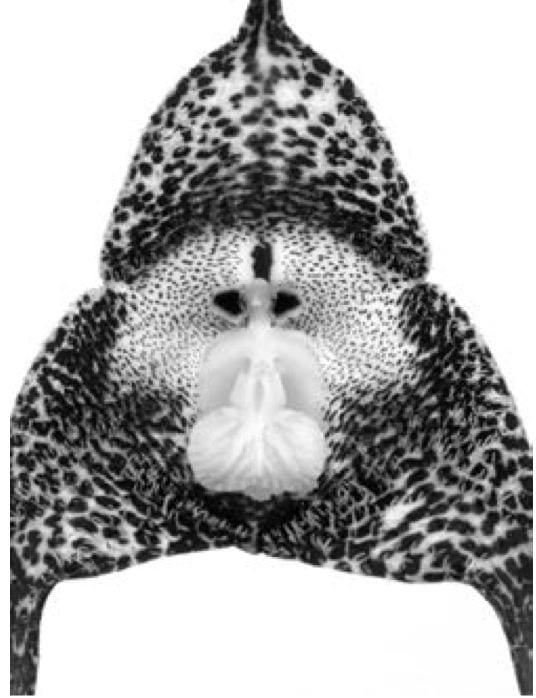

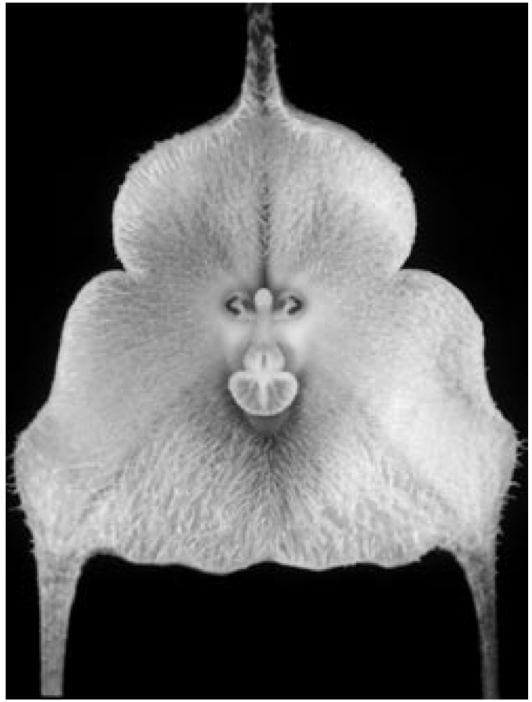

Twelve Portraits of the Dracula Orchid: A Photoessay

- Orchids are an irresistible attraction, and Andean forests were looted and destroyed to satiate the fever for this delicate flower.

T and little-known chapters of terrible tragedy dating back to Greek mythology. Back then, Orchis, the son of a nymph and a satyr, encountered the entourage of Dionysios, the son of Zeus and god of ecstatic celebration, in a forest. Suddenly infatuated with a priestess accompanying Dionysios, Orchis lost his head and tried to rape her. She defended herself and ordered wild beasts to kill him. However, as she gazed at the beautiful corpse lying at her feet, she repented her decision and asked the gods to return Orchis to life. The gods, moved by her plea, revived him and transformed him into an orchid flower.

In other cultures over the course of history, the orchid—a symbol of passionate love that is the symbol of aesthetic perfection—also is tied to bloody and brutal events. In southern Asia, orchid petals are the wrinkled dress of a vanquished goddess. In ancient Chinese paintings, serene brushstrokes depict orchids, plums, chrysanthemums and bamboo in silent contemplation of thousands of years of ruthless wars. In pre-Columbian cultures, the prized use of orchids for nutritive, medicinal and religious purposes transformed the orchid, along with other species, into an incentive for the devastating Spanish hordes. As of the latter part of the 19th century, however, the orchid’s misfortune manifested itself with more ferocious intensity. The voracious desire of Victorian Europe for this flower set off an interminable chain of deaths, beginning with that of millions of different orchid species that perished as a result of the dismal condition of the journeys on the way to exile. The disappearance of so many species in the midst of hurricanes and shipwrecks is almost unimaginable, a parallel drama to the heartless slave trade, transversing these same waters, all victims of this cruel market.

Meanwhile, the Andean forests were looted and destroyed to satiate the fever for this exquisite love of the delicate flower. Entire jungles were torn down to obtain the orchids residing within their dense foliage, while others were destroyed by this new type of hunter so that their competitors could not get their hands on certain precious species, making the orchids more valuable for those who had obtained them first. In strange revenge, many of these men paid for the boldness of this mass abduction with their lives, without distinguishing whether their purpose was scientific, commercial or just an irrepressible whim. Almost all of these orchid hunters, caught in the chains of an irresistible and fatal attraction, ended their lives as cadavers among the orchids, in the midst of these exuberant forests that are still being destroyed in a systematic and fierce manner by cutting, cattle-herding, and the indiscriminate aerial bombing of chemical fumigation of extensive areas that are the home of endemic species.

Colombia, the country that has the reputation for having the richest diversity of orchids in the world, also has abundant cases of deaths arising from the pursuit of this beautiful flower. Great figures in the history of botany and anonymous collectors arrived in these jungles, like hypnotized beings, following in a ominous ritual: Aimé Bonpland, a French explorer and botanist who ended his life as an orchid hunter on the Uruguay-Brazil border; Victorian merchant William Arnold, who disappeared in the thunderous torrents of the Orinoco River; David Bowman, victim of dysentery in Bogotá; German consul Friederich Carl Lehmann in Popayan, also a miner and orchid specialist, killed on the Timbiquí River; Albert Millican, collector, painter, photographer and author of the book Travels and Adventures of an Orchids Hunter, whose bones rest since 1899 in the Victoria, Caldas, cemetery after a fierce knifing; and the famed Gustavo Wallis, who perished of yellow fever and malaria in the Andean mountain mists. The list goes on and on. They were not the only victims of this mortal fate; many of the herbaria, collected with great effort, perished in the violence of local conflicts and the European wars, starting with that of José Celestino Mutis, quickly removed from the violence of Bogotá in a rescue effort, but losing part of the material in the twists and turns of the flight. The fabulous herbarium of the celebrated orchid specialist Heinrich Gustav Reichenbach was practically burnt to the ground during World War I. Rudolf Schelchter’s great herbarium in Germany was destroyed in 1943 by bombs. Many of the extensive series of engravings that José Celestino Mutis gave to Alexander von Humboldt, subsequently donated to the city of Berlin, were also destroyed in the bombing. Many of Europe’s botanical gardens suffered the same fate.

Around the middle of the 20th century, the difficult conditions of public order began to keep foreign botanists away from our jungles, and the search for orchids was left in the hands of Colombian collectors. With only a few exceptions, these Colombians have found themselves on the list of those who perished in the search for the exotic flower: José María Guevara, José María Serna, Evelio Segura, Bernardo Tascón, are just a few names among the many unnamed and unknown victims sacrificed in the tragic saga of the Scorpion Flower, a saga that began with the fate of Orchis in that mythical tale of long ago.

La trágica saga de la Flor de Escorpión

Por Jorge Mario Mœnera

Casi nadie sabe que en la historia de las maravillosas orquídeas existe un capítulo fatal de terribles tragedias de carne y hueso. Desde un principio, en la mitología griega, Orchis se encuentra en el bosque con el cortejo de Dionisios y pierde la cabeza por una de las mujeres que lo acompañan, intenta poseerla por la fuerza y ella, para defenderse, le ordena a las fieras el monte que lo maten pero, al ver el hermoso cadáver, ella se arrepiente de su orden y le implora a los dioses que le devuelvan la vida. Estos, conmovidos con su súplica, lo reviven transformándolo en orquídeas.

Asimismo en otras culturas la aparición de esta flor que es el símbolo del amor apasionado y de la perfección estética, está ligada a sucesos sangrientos y brutales: en el sur de Asia son sus pétalos el ajado vestido de una diosa vapuleada; en las pinturas de la antigua China las orquídeas, junto a los ciruelos, los crisantemos y el bambú, contemplan, desde serenas pinceladas, el transcurrir de milenios de despiadadas guerras. En las culturas precolombinas, su preciado uso alimenticio, medicinal y religioso las convierten, junto con otras especias, en acicate de la devastadora horda española. Pero es a partir del siglo XIX cuando su fatalidad se manifiesta con mas feroz intensidad. La voracidad que se desata en la Europa victoriana por esta flor acarreará una interminable cadena de muertes, empezando por la de millones de ejemplares de orquídeas muy diversas que perecieron por las tétricas condiciones de los viajes rumbo al exilio. Es inimaginable la desaparición de tantas especies en medio de huracanes terribles y naufragios, en un drama paralelo al del comercio de los esclavos que surcaron las mismas aguas, todos presas de ese cruel mercado.

Mientras tanto, los bosques eran saqueados para saciar la fiebre de la exquisita afición. Selvas enteras fueron derribadas para apoderarse de las orquídeas que habitaban sus galerías y sus copas y, otro tanto fue depredado por este nuevo género de cazadores para que sus competidores no pudieran conseguir determinadas especies preciosas y quedaran solo en poder de alguno de ellos. En una extraña venganza, muchos de esos hombres pagaron con sus vidas la osadía de ese rapto masivo, sin discernir si su propósito eran científico, comercial o tan solo un irrefrenable capricho. Casi todos ellos, caídos en las redes de la irresistible y letal atracción, terminaron sus vidas siendo cadáveres entre orquídeas, en medio de estas exuberantes selvas que siguen siendo destruidas de forma encarnizada y sistemática por la tala, la ganadería, la fumigación química indiscriminada y los bombardeos de extensas áreas que son nicho de especies endémicas.

Colombia, país que tiene la fama de ser el mas rico en especies de orquídeas en el mundo, abunda también en casos de muertes surgidas en la persecución de esta bella flor. Grandes personajes de la historia de la botánica y anónimos recolectores llegaron a estas selvas, como hipnotizados, dando los pasos de un fatídico ritual. Pasaron por aquí Aimé Bonpland, quien terminó su vida de buscador de orquídeas en los límites de Uruguay y Brasil, muriendo dos veces seguidas, la primera de muerte natural y la otra, de varias puñaladas. William Arnold, comerciante victoriano, desaparecido en los estruendosos raudales del Orinoco. Falkenberg, consumido por las fiebres y el delirio en las selvas de Panamá. David Bowman, fue víctima de una imparable disentería en Bogotá. Friederich Carl Lehmann, minero y orquideólogo, fue durante muchos años el cónsul de Alemania en Popayán, donde vivió buena parte de su vida hasta ser asesinado mientras recorría el río Timbiquí. Albert Millican, recolector, pintor, fotógrafo y autor del libro Travels and Adventures of an Orchids Hunter, cuyos huesos reposan desde 1899 en el cementerio de Victoria, Caldas, después de una feroz cuchillada. El renombrado Gustavo Wallis pereció de fiebre amarilla y malaria entre las brumas de las cimas andinas. Enders, uno de los mas grandes recolectores, murió tiroteado en una calle en Riohacha. Y no solo fueron ellos las víctimas de este sino mortal; también muchos de los herbarios que con gran esfuerzo colectaron, desaparecieron por la violencia de los conflictos locales y de las guerras europeas, empezando por el de José Celestino Mutis que fue sacado de afán de Bogotá, perdiéndose parte de su material en los recovecos de la huida. El fabuloso herbario de Reichenbach fue casi todo incinerado durante la Primera Guerra Mundial lo mismo que el gran herbario de Rudolf Schelchter, consumido por los bombardeos de 1943 en Alemania. También se perdieron, por la misma causa, una gran serie de láminas que José Celestino Mutis le regaló a Humboldt y este donó a la ciudad de Berlín. La misma suerte corrieron muchos de los jardines botánicos de la Europa de ese entonces, en donde previamente sus encargados habían cocinado a centenares de miles de orquídeas tratándolas de adaptar a invernaderos que tenían todas las características de las cámaras de gas.

Hacia mediados del siglo XX las difíciles condiciones de orden público terminan alejando a los investigadores extranjeros de nuestras selvas por lo que a partir de esa fecha la búsqueda de orquídeas queda en manos de recolectores colombianos que, salvo contadas excepciones, han engrosado la lista de muertos en pos de la exótica flor: José María Guevara, José María Serna, Evelio Segura, Bernardo Tascón, son algunos nombres conocidos entre tantos desconocidos sacrificados en la trágica saga de la Flor de Escorpión.

Fall 2004/Winter 2005, Volume III, Number 1

Jorge Mario Múnera is a Colombian photographer and was the winner of the 2003 DRCLAS Latin American and Latino Art Forum. He earned first place in Colombia’s National Photography in 1988. His work has been published in Orfebrería y Chamanismo, with text by anthropologist Gerardo Reichel Dolmatoff, as well as in Orquídeas Nativas de Colombia, volumenes 1, 2, 3, 4 with texts by various authors; El tren y sus gentes, with texts by Belisario Betancur et al; Vista Suelta, which won the National Photography Prize; and El Corazón del Pan with text by Antonio Correa. Many of these books have been published by Sirga Publishing. Múnera is currently preparing editions of Memoria de Festejos Populares and La arena y los sueños. Contact:<jmmmunera@etb.net.co>.

Jorge Mario Múnera es fotógrafo colombiano. I Premio Nacional de Fotografía, 1988. Ganador de DRCLAS Art Forum 2003. Parte de su obra ha sido publicada en Orfebrer’a y Chamanismo, texto de Gerardo Reichel Dolmatoff. Orquideas Nativas de Colombia, volœmenes 1,2,3, 4, textos de varios autores. El tren y sus gentes; texto de Belisario Betancur. Vidas Casanare–as, textos de varios autores Vista Suelta, Premio Nacional de Fotografia y, El Corazón del Pan con texto de Antonio Correa. Algunos de estos libros han sido realizados por Sirga Editor, su sello editorial. En la actualidad prepara la edición de Memoria de Festejos Populares y La arena y los sueños.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter: Flora and Fauna

Ellen Schneider’s description of Sandinista leader Daniel Ortega in her provocative article on Nicaraguan democracy sent me scurrying to my oversized scrapbooks of newspaper articles. I wanted to show her that rather than being perceived as a caudillo

Bilingual Aesthetics: A New Sentimental Education

After an exhausting game of soccer with a crew of Mexico City street children, Vicente, a young teenager of 13 said, “Vamonos a la verga.” It was my third day with Casa Alianza, the international…

Nature and Citizenship

Two first-time visitors to the Galapagos archipelago begin their experience in exactly the same way. Two hours after departing mainland Ecuador, their plane descends towards the island of…