Encounters with Guna Celebrations

Photos by James Howe

In 1681, an injured pirate named Lionel Wafer spent several months in the Darién region of eastern Panamá recuperating with the local Indians, who, he noted, gathered occasionally to enjoy a fermented corn drink. Wafer’s carefully neutral account of these parties, published in 1699, was not echoed by later observers. Most of them were appalled by what they saw, and in the early 20th century, missionaries and government officials tried, unsuccessfully, to impose prohibition.

By then the Indians, known today as the Guna or Kuna, had moved out onto small inshore islands along the Caribbean coast, where, among other things, they carried on holding the same celebrations as the ones in Wafer’s day. What their indignant critics did not understand is that these events, by no means simple booze-ups, marked a girl’s coming of age; that celebrants drank and toasted each other with great solemnity; and that between times the abstemious Guna did not touch alcohol at all.

- Enthusiastic young women serve chicha fuerte to the next group of drinkers.

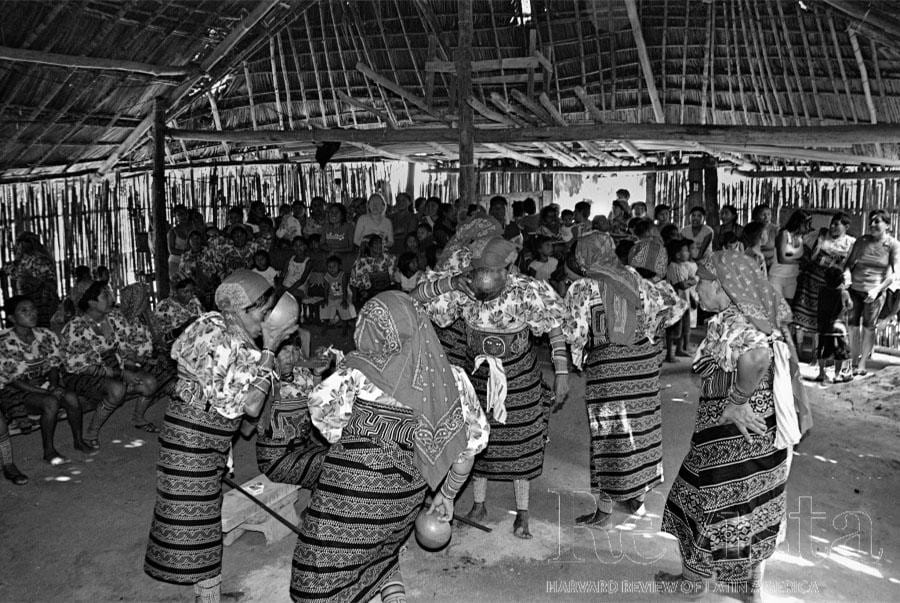

- At a ceremony in honor of a young girl, senior relatives, all of whom are wearing identical outfits, drink in unison, while other women look on.

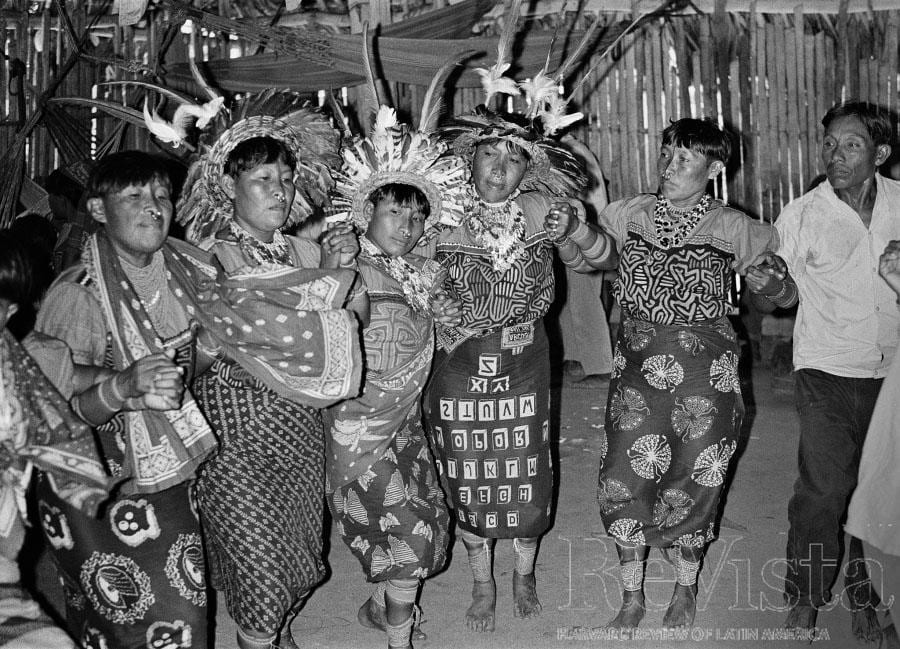

- Two dancers wearing pelican bone necklaces blow smoke from long cigars, taking the lighted ends into their mouths. The smoke converts into invisible cane beer or chicha fuerte for spirits in the room, who would otherwise be jealous of human enjoyment.

- Women dance in a circle, wearing the feather headdresses belonging to the ritualists who preside over the ceremonies.

My wife June and I first experienced these feasts for ourselves in 1970, three centuries after Wafer, when we spent a year in an island community. As a graduate student in anthropology, I had been sent to study local politics, but—like many other fieldworkers—I found I could not ignore major events just because they lay outside my chosen topic. In the case of the Guna, that meant drinking parties.

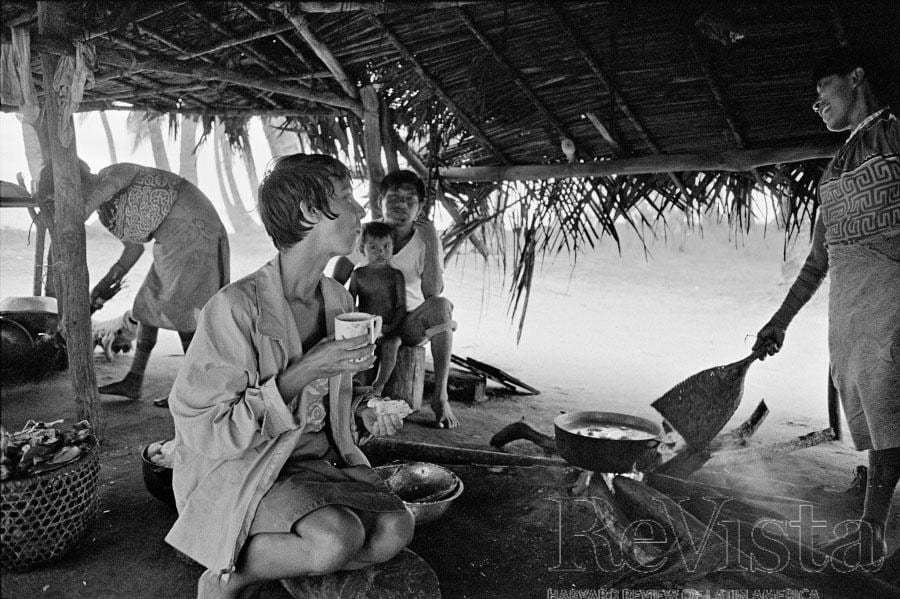

One celebration in particular we observed close up, sponsored by a close friend named Charlie Hernández. It started with his anxiously gathering fish, game, bananas and money for his daughter’s rite of passage. When villagers cooked cane juice for the dark brew known in Spanish as chicha fuerte, June helped fan the fire.

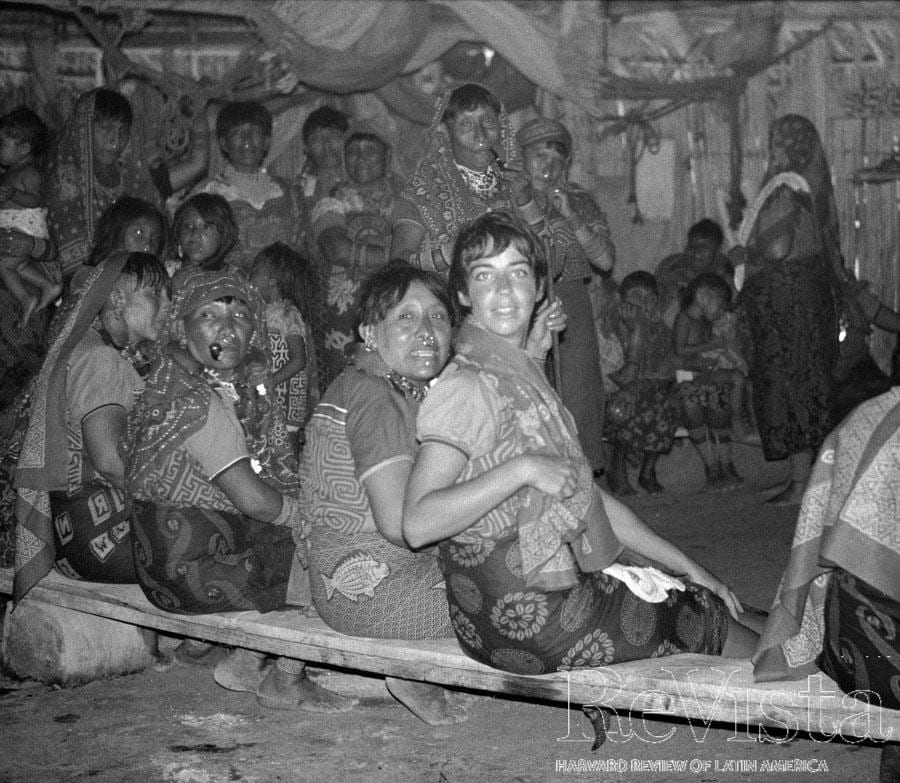

Two weeks later, when the chicha had reached maturity and June’s friends had outfitted her for the occasion in native dress, we joined in several days of drinking, singing and dancing, while the presiding ritualists, called “flutemen,” performed a long esoteric chant celebrating Charlie’s daughter’s passage to adulthood.

In other ceremonies that year, June and I were encouraged to participate and even to take photographs, so long as they did not include obviously intoxicated women. In the longer of the two types of ceremony, men and women spent a whole day in elaborate preparations—making flutes and rattles, weaving hammock ropes, and painting designs on balsawood boards—before settling in to several days of revelry. Village elders invariably complained afterwards of celebrants’ misbehavior, but stern and completely sober watchmen were always on the lookout for out-of-bounds actions.

- Women fan a fire to cook sugar cane juice that will ferment into chicha fuerte

- Women dance in a circle, wearing the feather headdresses belonging to the ritualists who preside over the ceremonies.

- Senior men enjoy themselves during the ceremonies.

- A group of Guna volunteers and specialists chant and drink as they weave ropes for a ceremonial hammock.

Over the next four decades, I drank at several chicha celebrations but took no more photographs. A few images were published and exhibited, but the original negatives, most of them exposed in low light, languished in a drawer until digital scanning and editing rescued them in the new century.

In 2011, the revived photographs were exhibited in Panamá at the Museo del Canal Interoceánico, with the approval of the original villages and the official sponsorship of the Guna Cultural Congress. The large Guna crowd at the opening of the exhibit seemed every bit as pleased to see themselves on the museum walls as we were to display them.

- une Howe enjoys a welcoming drink at a friend’s kitchen during fieldwork.

- Senior men toast others before draining their cups of chicha fuerte.

By then, the Guna were photographing the celebrations for themselves. Two years before the exhibit, at a feast that occurred during a visit back to our field site, June sat with with an old friend from almost forty years before. As I stood nearby watching, marveling at the durability of Guna tradition, I wondered whether I might be allowed to bring out my camera. A moment later I realized that many of the younger people in the room were already snapping pictures on their digital phones and cameras.

Spring 2013, Volume XII, Number 3

James Howe is emeritus Professor of Anthropology at MIT and author of several books on Guna culture and history. He thanks William Morse Editions of Boston for rescuing and printing the photographs.

Related Articles

The Panamanian Novel

Pueblos perdidos, the novel which earned Gil B. Tejeira Panamá’s Miró Literary Prize for 1963, tells the story of Gatún Lake, at the time the largest artificial…

Panamanian Culture

Panamanian culture has roots in at least three continents. It’s a heterogeneous culture, embracing elements from various communities that coexist peacefully…

Panama City

On May 8, 2003, the Bay of Panamá suddenly turned red. The Coca-Cola factory had spilled a massive amount of non-toxic red chemical dye and was eventually…