Engravings From the October Revolution (1944-1954)

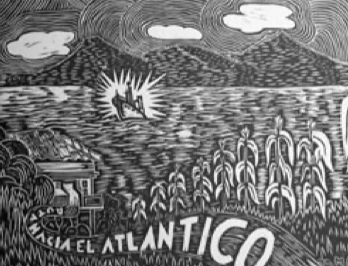

The democratically-elected Arbenz government hoped for economic prosperity through economic reform and a highway to the Atlantic.

In 1952, the Presidential Information Secretary through the initiative of Luis Cardoza y Aragón contracted the Mexican engraver Arturo García Bustos, to organize an engraving workshop in the National School of Plastic Arts, sponsored by Guatemalan Magazine and the Saker-Ti Group (Amanecer). García Bustos had earlier set up a Mexican Popular Graphics Workshop. In that workshop, the Mexican Revolution had been the principal theme, and a great part of the artistic production was aimed at supporting revolutionary changes with a clear popular-didactic purpose, bringing the masses closer to the revolution and the changes it involved.

The Mexican artist arrived in Guatemala at a key moment in the country’s history. The government was attempting to carry out a series of economic, political and social changes for the benefit of the Guatemalans. The revolutionary effervescence of the moment provided inspirational themes for the young artists and was used for political propaganda for the government of Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán (1951-1954). Contests were held and scholarships awarded, as well as contracts for the elaboration of revolutionary posters. Guatemala was filled with posters made in the Free Engraving Workshop.

Engraving as a technique uses a chisel over a surface to sketch out a slogan, a figure or a representation of any object. It can be made on metal, wood, rock or rubber plates used to print or stamp with pressure or rubbing to obtain several copies of the work.

Through its realistic expressionism, Guatemalan engravings acquired the character and form of propagandistic posters, serving as a vehicle for aesthetic-functional information. The engravings are political propaganda that respond to a moment in history. They were inspired in the agrarian reform, anti-imperialism and advocacy of non-intervention in the internal affairs of Guatemala, social struggle and the economic aspirations aroused by the Atlantic Highway and other new means of communication. The revolution was besieged by its enemies, the coffee oligarchy, the Catholic Church, powerful Guatemalan interests and the United States. Thus, it used the posters to publicize its achievements and to defend itself against the aggression to which it had been subjected.

In 1954, after Arbenz was overthrown, Guzmán suspended the engraving school, but it started up again under Enrique de León Cabrera in 1957 with the introduction of new techniques. However, many of the former students did not continue their studies because of political persecution. The legacy of the Free Workshop of Engraving forms part of an important period in the political and social life of Guatemala, a period frustrated by the overthrow of Arbenz, but which defended its achievements in many ways—even through the art of engraving.”

Special thanks to Julio Galicia Diaz, director of the Archivo General de Centro America; Vitelio Castillo, director of the Division of Publicity and Information of the Universidad de San Carlos; Gladis Barrios, Director of the Museum of the Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala and Rogelio Chachon, photographer of the Universidad de San Carlos Guatemala and Oscar Pelaez for making the publishing of these engravings possible.

Grabados guatemaltecos: arte de la Revolución de Octubre (1944-1954)

Por Oscar Guillermo Peláez Almengor

En el año de 1952, la Secretaria de Información de la Presidencia de la República, por iniciativa de Luis Cardoza y Aragón contrató al grabador mexicano Arturo García Bustos, para organizar un Taller Libre de Grabado en la Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas, patrocinado por la Revista Guatemala y del Grupo Saker-Ti (Amanecer). El mexicano García Bustos se había formado en el Taller de Gráfica Popular Mexicano. En aquel taller la Revolución Mexicana había sido el principal motivo temático. Una buena parte de su producción artística apoyaba los cambios revolucionarios con una clara tendencia didáctico-popular, acercando a las masas a la revolución y los cambios que esta entrañaba.

El artista mexicano llegó a Guatemala en un momento clave en la historia del país. El gobierno intentaba una serie de cambios económicos, políticos y sociales para beneficio de los guatemaltecos. La efervescencia revolucionaria de aquel momento proporcionaba temas inspiradores para los jóvenes artistas. El Taller Libre de Grabado guatemalteco fue utilizado para la propaganda política del gobierno de Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán (1951-1954), se efectuaron concursos, se ofrecieron becas y contratos para la elaboración de carteles revolucionarios. Guatemala fue inundada de carteles elaborados por los participantes en el Taller Libre de Grabado.

El grabado, como técnica, se fundamenta en “arte de grabar” que es señalar con un cincel sobre una superficie, un letrero, una figura o representación de cualquier objeto. El grabado se realiza sobre planchas de metal, madera, piedra y hule para imprimir o estampar por medio de presión o frotación, copias de una obra, las que de acuerdo al soporte, definen las técnicas siguientes: Xilografía, grabado sobre madera; Punta Seca, grabado sobre metal; Litografía, grabado sobre piedra; Agua Fuerte, grabado sobre metal y Linóleo, grabado sobre hule. En el Taller Libre de Grabado sus miembros se expresaron a través de estas técnicas motivos comprometidos en el afán propagandístico del gobierno y la situación política de aquellos años.

El grabado guatemalteco lleva implícito la euforia revolucionaria y las conquistas sociales de la Revolución de Octubre. A través del expresionismo realista, adquiere carácter y forma de cartel propagandístico, siendo vehículo de información estético-funcional. Los grabados son propaganda política que responden a su momento histórico. Fueron inspirados en la Reforma Agraria, el anti-imperialismo y la no intervención en los asuntos internos de Guatemala, la lucha social y las proyecciones económicas que significaban los nuevos medios de comunicación como la Carretera al Atlántico. Así mismo, los servicios como el Puerto de Santo Tomás y la Hidroeléctrica de Marinalá, fueron temas encargados y de los cuales se hicieron muchas copias. La revolución asediada por sus enemigos, la oligarquía cafetalera, la Iglesia Católica, Estados Unidos y sectores poderosos del país, utilizo los carteles elaborados en el Taller de Libre de Grabado para dar a conocer sus logros y defenderse de la agresión que estaba siendo objeto.

En 1954, luego del derrocamiento de Arbenz Guzmán se tuvo en cuenta el sesgo político del Taller y se cerró la Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas. El cierre duró varios meses y se inició su reestructuración. En 1957 resurgió la clase de grabado, fue nombrado Enrique de León Cabrera para impartirla. En aquel momento se introdujeron nuevas técnicas, sin embargo muchos de sus anteriores alumnos no continuaron debido a la persecución política a la que se vieron sujetos. El legado del Taller Libre de Grabado forma parte de una etapa importante en la vida política y social de Guatemala, una etapa frustrada por el derrocamiento de Arbenz, pero que defendió sus logros incluso a través del “arte del grabado”.

Spring/Summer 2005, Volume IV, Number 2

Oscar Guillermo Peláez Almengor is the DRCLAS Central American Visiting Scholar, and Professor of the Center for Urban and Regional Studies, University of San Carlos, Guatemala.

Oscar Guillermo Peláez Almengor es académico visitante centroamericano DRCLAS y profesor del Centro de Estudios Urbanos y Regionales de la Universidad de San Carlos, Guatemala.

Related Articles

Introduction: Bush Administration Policy

So it is the policy of the United States to seek and support the growth of democratic movements and institutions in every nation and culture, with the ultimate goal of ending tyranny…

International Symposium in Puebla

It is likely that Don Quijote first reached the Western hemisphere—in what was, at the time, lightning speed—as a stowaway. On September 28, 1605, Franciscan commissioners of the…

Adiós 61 Kirkland

For the past eight years, the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies has made its home at 61 Kirkland Street. Countless film screenings, celebrations and roundtable discussions…