Environmental Education

A Working Perspective

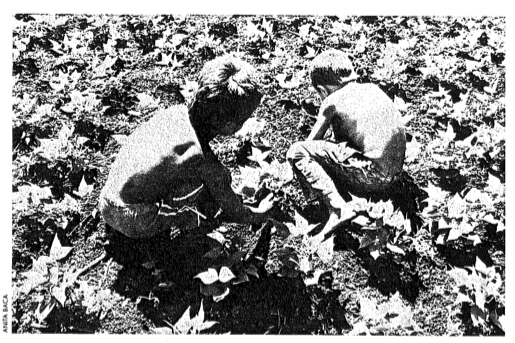

It is often children, barefoot and eating, who spray these chemicals on the fields.

Majestic mountains tower over a small community of pink, lime green and pale blue houses. Children play baseball with a rolled-up sock for a ball; women are sweeping their patios and cleaning the rice, and the men are laboring in the fields, plowing, hoeing, planting food to sustain their families. This is Los MartÃnez, a rural, agricultural village nestled in the mountains of San Jose de Ocoa in the Dominican Republic. It could be considered a small slice of tropical paradise, but it is also one of many such small communities in grave danger of losing their livelihood to the effects of environmental devastation.

The people of Los Martinez depend on agriculture to support themselves. Large harvests of carrots, eggplants, tomatoes and other vegetables slowly make their laborious journey down the mountain to the city markets. But, the farming techniques, once successfully used by their ancestors, are now resulting in lower yields with higher production costs. In Los MartÃnez, the farmers continually lament how the soil doesn?t produce as much as in the past, unaware of the impact of their own farming methods such as the use of antiquated slash-and-burn agriculture. Agriculture cannot continue in the same manner, or their children will inherit infertile soil.

Change is a slow process, but the steps have begun. The greater hope for change lies with the very children of the community through environmental education. As a Peace Corps volunteer, I have been working together with community teachers to begin fostering a love and respect for our environment. The most obvious environmental problem facing the children is that of trash. Plastics and styrofoam containers have made their way up the mountain and onto the community road. Trash containers are few and far between; the natural inclination is to throw trash anywhere. We have now celebrated several trash clean-up days, and have dug enormous holes for containment. In celebration of Earth Day, we cleaned and then planned a day for every household to find and decorate its own trash can. The children have also become involved in the reforestation process. We have taught a unit on trees that culminated on Arbor Day when each child received a fruit tree to plan and protect. We have also developed a unit for the coming school year on insects and the proper use of insecticides and their alternatives. The active response from children has been inspiring.

Their parents, Dominican farmers, face many grave issues. Development agencies and Peace Corps volunteers like myself have a plethora of environmental projects to tackle. These are battles that no one individual can take on alone; community organization is the key to addressing them. In the last year and a half as an agriculture Peace Corps volunteer, I have been fortunate to work with a strong agricultural association and women?s group in addition to a strong nongovernmental organization (NGO) in the region. I have also been honored to work with 35 wonderful students in our community school. We have together begun taking steps towards changing our environment.

Our most measurable project is reforestation. The local NGO, Asociacion para el Desarrollo de San José de Ocoa, has provided the trees, mostly a native pine species. We have formed work brigades including representatives from every household, and headed for the mountains. In my time in the community, we have planted a good 20,000 trees. Another part of that job is fire prevention, so we have cleared the land on both sides of the reforestation so that no fire may reach the trees. The community is proud of this job, and it has a lasting positive impact.

Carlos Antonio Amela, 10, of Masaya, Nicaragua, exclaims in his drawing, “Stop it! Let’s Save Our Country”

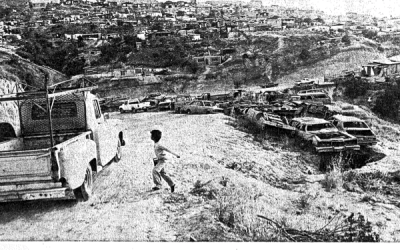

These kinds of projects link the community and the children to the process of environmental education, and hopefully to a slowing or even a reversal of the devastation of nature. The land used by the farmers of Los Martinez would not even be considered fit for farming within the United States because the slope of the land is too high. One hard rain washes all of the topsoil nutrients away. Slash-and-burn agriculture has led to the deforestation of the mountain land; shrubs and spiny trees have taken over the once cloud forest. The burned land yields just one or two seasons worth of carrots. The nation-wide deforestation has also contributed to a grave shortage of water.

Modern technology has added its own damages in the form of chemicals. The green revolution brought insecticides, herbicides, and fertilizers to often illiterate farmers. These chemicals are usually applied without heeding safety measures or proper measurements indicated on the labels. The overuse of chemicals has rendered much of the soil sterile and, as insects build resistance to these toxins, various plagues become more and more difficult to battle. In addition, it is often children, barefoot and eating, who spray these chemicals on the fields. Also, it is not uncommon to see farmers using chemicals that have been banned in the United States such as DDT and Paraquat. Doctors partially attribute the rise of cancer, birth defects, and allergies to the abuse of these chemicals.

In terms of agricultural change, I have been working with the agricultural association in the use of protective barriers for terracing, the use of cover crops for soil replenishment, and the development of a chemical-free integrated pest management program. I show all of the various techniques of a demonstration plot and, after a series of short courses, have begun working with several farmers on small plots of their own. Although the farmers are reluctant to change the only way they know of supporting their families, the dramatic change in soil that leguminous cover crops produce has farmers excited enough for a small experiment of their own. The use of tobacco, garlic, Nim, and other plants as natural pesticides has captured the interest of farmers, but they are much less willing to experiment with controlling a crop that represents their livelihood.

The issues facing Los Martinez are not rare. Not only do other Dominican communities face them, so do rural communities throughout Latin America. The loss and sterility of topsoil is a world-wide crisis, as is the overuse of agro-chemicals. Water shortages resulting from deforestation are not uncommon either. The mountains of trash with nowhere to go may be the first wake-up call to communities in terms of environmental crisis. We can only hope that the community members will join together as those in Los MartÃnez have, and that development agencies continue to provide technical and sustainable support. Immediate community action and education are necessary, or the generations to come will be unable to farm.

Fall 1998

Leslie Dominguez is an agriculture Peace Corps Volunteer in the Dominican Republic. She is also developing a gender program for a local NGO. She is a graduate of Oberlin College.

Related Articles

Caballero wins Colombia’s top journalism prize

Building on work she started at the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, investigative journalist Maria Cristina Caballero has won Colombia’s top journalism prize…

Between Vengeance and Forgiveness

At the close of this century of death camps, killings fields and desaparecidos, there is perhaps no more urgent question than the one raised in Martha Minow’s useful new book: Can societies…

The Environment in Latin America

This issue of the DRCLAS NEWS deals with some of the environmental problems of Latin America, one of the priorities of the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies…