Eréndira Ikikunari

Celebrating Indigenous Cultural Heritage

Hucha mítetixapquia escacsi hupiringa, máteru cuiripuecha. Atahpiticha encacsi tyámu xucuparhapca ca engacsi cacapequa úquaaca imaechani engancsi cuahpequarhenga. Ma cuiripuhcu no cherheaspti. Yurhistsquiri ma enga naneni, hamemquia Eréndira arhicurhispti…

“We had heard about the intruders: Warriors covered with iron who descended from heaven and killed all who dared oppose them. The only one that didn’t fear them was a girl, barely a woman: Her name was Eréndira…”

The language is Puréhpecha, spoken by the indigenous people who had lived in Michoacán, Mexico, long before the arrival of Europeans. They were one of the most powerful pre-Columbian empires, only second to their worst enemies: the Aztecs. Actually, they were never conquered by anyone, so their descendants still maintain many of their traditions and customs.

Synopsis

The feature film Eréndira Ikikunari (2006) is based on a 16th century legend. It tells the story of a young girl, Eréndira, who became an icon of bravery during the destruction of her world by the Spanish conquistadors. The intruders took advantage of conflicts and discord among the Mexican natives that allowed the newcomers to reap the spoils of a country divided. But Eréndira refused to allow her nation to be destroyed and stood up against the social conventions that prohibited women from participating in warfare. It took extreme courage for her to capture and learn to ride one of the Spaniards’ horses— seen as terrifying creatures by the natives. However, in this fashion, Eréndira won the respect of tribal leaders and became a symbol of resistance and the preservation of her culture. She was an exceptional woman, who fought to attain the dignity and respect that her culture only granted men.

Background

When I was shooting a mural depicting the History of Michoacán for a documentary film about the Mexican painter Juan O’Gorman, I discovered the figure of an almost naked Indian Amazon facing the bloody, iron-clad Spanish conquistadors. Immediately I thought: “This is a great theme for a movie.” The idea of doing a film on a real red-blooded heroine was very attractive; first, I didn’t have to invent or idealize anything, and second, the theme countered the low status that women had in pre-Columbian cultures and the degree of invisibility in which women are maintained even today.

The plot is based on two sources: the widespread legend of Princess Eréndira and the 16th century illustrated manuscriptRelación de Michoacán, written immediately after the conquest. This codex narrates the history of the Puréhpecha people, from their mythical origin until the arrival of the Europeans. The two accounts complement each other as two pieces of a puzzle, although giving opposed views of the conquest, the Relación being the official history written by the victors, and the legend, handed down by oral tradition, being the only history book of vanquished peoples.

We planned to stage the film in locations in Michoacán: the Paricutín volcano as the abode of the gods, Lake Pátzcuaro, the ruins of two pre-Columbian cities and the spring of the Cupatitzio river. As we would be working in actual ruins instead of building sets, we decided that the characters’ wardrobe and makeup should be based on the archaeological sources (the drawings of the codices and representations of people in ceramics and stone) and the contemporary crafts of the Puréhpecha (pottery, textiles and the attire of the folk dancers).

Costume

The costume design was developed from the Relación de Michoacán illustrations, where all the social strata of the pre-Columbian Puréhpecha are depicted. Considering that these images are stylizations, their translation into three-dimensional costumes was a challenge. Instead of using materials such as tiger or deer leather, tropical bird feathers, raw cotton or jute fabrics, we employed materials used by contemporary ethnic groups, like straw mats –which served to create armor– or hand-woven fabrics. Instead of embroidering them, we used textile paint, imitating the codex’s drawings. The end result was very interesting, achieving the look of a “cinematic pre-Columbian codex.” Another challenge was to present the conquistadors as supernatural beings. We wanted to see them as the Indians did, as “ironclad warriors that had descended from heaven.” We hit upon an answer in the folk dance of the “Curpitis,” where we see natives wearing wooden masks that depict white men. Their costumes were a combination of renaissance armor and the wardrobe of the “Curpitis,” including, of course, the masks. Puréhpecha devil masks were used to represent pre-Columbian gods. Even the horse wore a metallic mask, acquiring by association a divine quality. This goes on, of course, until the Indians unmask the invaders, realizing that they are merely human. The only one that never loses his is the horse!

Makeup

Eréndira Ikikunari’s makeup was developed from an idea from my previous feature on the Aztecs of Mexico, Return to Aztlán, in which we substituted body makeup for expensive costumes (expected in a period piece). In the Mixtec pre-Columbian codices, characters were usually decorated all over with signs, and certain Mexican indigenous tribes still paint their bodies for their ceremonies. It was surprising to discover that a practically nude person covered with body makeup appeared to be richly attired, and also, as in the case of the depiction of gods, was transformed into an extraordinary being.

In Eréndira we went even further. In the Relación we read that the great warriors used to cover their bodies with the soot from dense black smoke of green wood bonfires. This gave us the idea of using different qualities of black body makeup to distinguish the great warriors from the foot soldiers. Also, as the film deals with a fratricidal war, the rebels were painted solid black and the Spaniards’ allies had white markings upon their black makeup. In this way we could show that all belonged to a common culture, although they were fighting each other as harsh enemies. Eréndira had a red stripe on her face, to show that she was struggling for all of her people.

Makeup also served to give dignity and greatness to the characters, and to distinguish social strata and trades. As the film starts with Eréndira preparing for her wedding, we created a “wedding makeup” based on a pre-Columbian clay figure. Also, in the Relación, characters appear with faces painted in different colors, information that was very useful as it broadened our makeup palette.

Shooting the Film

To make the film I sought the collaboration of the indigenous community as well as input from scholars and linguists. I wanted the indigenous voice and perspective to be the true narrator. Then, instead of working with professional actors speaking Spanish or English, I chose to train indigenous actors, speaking their own tongue, acting in their imperial pre-Columbian cities, wearing the outfits of their ancestors and recreating a very important episode of their own history. This gives the film a very special authenticity; more than mere entertainment, it’s a Statement of the Original Peoples regarding their own History.

The dialogue is mostly spoken in a Puréhpecha with an ancient flavor, mixed with a little 16th century Spanish and Latin. With the help of linguists from several indigenous villages, we had to create a dialogue that everybody who knows the tongue could understand. The actors, who were mostly authentic Indians acting for the first time ever, went through intensive rehearsals in the eight weeks before we started shooting. For the role of Eréndira we wanted to break away from the commonplace of mannish and superhuman heroines typical of U.S. action films. So we chose a young actress doing her first professional role in a very feminine way.

We started working on the shores of Lake Pátzcuaro, in the ancient imperial cities of Tzintzuntzan (the place of hummingbirds) and Ihuatzio (the place of coyotes), still mostly buried. The fact that we were working in the place where the original events took place also added a kind of magical aura and communion with living nature and the ancient gods. This was echoed in the actors’ performances and in the camera work. Due to the difficult shooting conditions, as we were working in exteriors, with natural light, with non-professional actors who were almost naked, the largest part was shot with three simultaneous cameras in digital cinema, one in high definition (HD) and two miniDVs. The other part of the film was shot with two S16 mm film cameras. This allowed the actors to perform without interrupting the flow of their emotions, as is usual in features. We also could take advantage of the continuity of the lighting conditions and colors of each hour of the day. There were many magical moments that were captured by the cameras in astounding photography.

Postproduction

The use of digital techniques during the editing allowed us to combine the beautiful drawings of the Relación de Michoacánwith live action, establishing a style that followed the Puréhpecha concept of the epic and allowed the rendering of a myth. So, through a non-realistic style, a world that we can’t possibly recreate is made credible. The story is finally told by the voice of an old Indian through the text and drawings of a codex. This combination of graphics and live action in collage form brought the form of the film near to the aesthetics of pre-Columbian codices while maintaining a very contemporary look.

The music was made from the sound recordings of the scenes. Human voices, sounds of nature, conches and drums, were used to create the music digitally. The film thus attained a very special unity, as all the sound, music and images stemmed from the same source.

Some Lessons

Such films on pre-Columbian themes are extremely rare and contribute to the awareness that our most important roots, especially in a large part of Latin America, are not only European. It’s true that since the conquest both indigenous cultural heritage and religions have been labeled as “primitive,” “useless,” “naive,” “inferior,” and “valueless,” as that served the Europeans to strengthen their dominion. Even today, the fact of being of non-European origin is a source of shame for many people in Latin America. During the premiere of the film at the Puréhpecha community theater in Pátzcuaro (the city where the O’Gorman mural is located), the response of the indigenous audience was extremely moving. One old lady who did not speak Spanish fluently said that she “was very happy because it was the first time she had understood a Mexican film.” One man told the audience very openly that since his childhood he was made to feel ashamed of his language and culture, but after watching the film he felt very proud. Those two comments were for me justification enough for having made the film, which, incidentally, did very well in Film Festivals all over the world and in box office receipts in Mexico. The film has also been shown in various indigenous communities, always resulting in discussions about the necessity of studying their own history, ending ancient grudges between villages, unifying the diverse dialects of their language, and longing for more Eréndiras.

Fall 2009, Volume VIII, Number 3

Juan Mora Catlett is a filmmaker and full professor at The University Center of Film Studies at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM). He has distinguished himself in developing a style of fiction cinema based on pre-Columbian cultural roots.

Related Articles

Coconut Milk in Coca Cola Bottles

Common knowledge has it that virtually any movie, once removed from its original cultural context of production and reception, might be either misunderstood and misperceived or re-interpreted and re-signified. Likewise, we may agree that national cinemas seek to define, challenge….

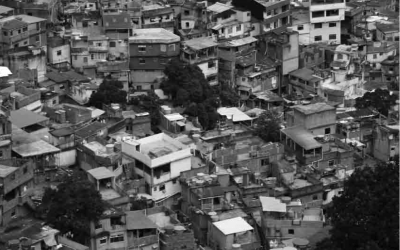

Neither the Sertão or the Favela

To frame the poetics of the ordinary in terms of subtlety and delicateness is to propose an antidote both for cynicism and for what I call Neo-Naturalism. Its appearance, at least in Brazilian cinema and literature, has been clearly identified, ranging from peripheral subjects…

Brazilian Cinema Now

Snow falling in the city of São Paulo, in southern Brazil? Taking a helicopter in São Paulo then arriving a few moments later in the deep wilderness of the Amazon jungle, half a continent further away to the north? Then meeting a white Asian tiger in the heart of the Amazon forest?…