First Take: New Technologies and New Narratives

In Ibero-American Cinema

Recent film trends in Latin America and beyond cannot be understood without examining new technologies and their impact on new narrative forms. That is why, in November 2008, the Real Colegio Complutense of Harvard University, together with the Universidad Complutense and the Universidad Castilla-La Mancha, sponsored a three-day international symposium in Cuenca and Madrid, Spain. The fruit of friendly collaboration with colleagues in Spain, most notably Ignacio Oliva, Fran Zurián, Josetxo Cerdán and Pilar Rodríguez, as well as with colleagues from Cuba (Luciano Castillo), Mexico (Juan Mora Catlett, Elisa Miller), Brazil (Denilson Lopes), Argentina (Gonzalo Aguilar, Ana Amado), Chile (Cecilia Barriga), Venezuela (Andrés Duque) and Costa Rica (María Lourdes Cortés), the symposium was the first installment in a still unfolding series of similar ventures on other topics. The next will be “cinema as history; history as cinema,” tentatively scheduled at Harvard University in November 2009.

The aim of the symposia is as simple as it is complex: to bring together critics, historians, filmmakers, screenwriters, producers, actors and others who share an interest in and/or commitment to cinematic production in Latin America, Spain, Portugal and the Caribbean in order to interrogate, as openly and dialogically as possible, the promises and pitfalls of a trans-Atlantic, Ibero-American rubric in which Spanish and Portuguese, rather than English or French, would be the primary tongues. Needless to say, it is somewhat risky, if not indeed illusory, to speak of Ibero-American cinema—or, despite the existence of a number of festivals, conferences, books, and collaborative efforts like our own, even to speak of Latin American or Iberian cinema—when what in fact prevails, still today, is a nationally delimited understanding of cinematic works or, more generally, audiovisual products, here Mexican, there Brazilian, and over there Spanish, as it were.

Brazilian film critic and historian Paulo Antonio Paranaguá already signaled the problems not with the more ample Ibero-American moniker but with the more established Latin American moniker in a book published in 2003 by the Fondo de Cultura Económica de España, Tradición y modernidad en el cine de América Latina (Tradition and Modernity in Latin American Cinema). In the words of Paranaguá: “Latin American cinema does not exist as a platform of production: the space in which virtually all projects are generated is purely national, at times even local, though there are transnational currents and continental strategies dating from at least the beginning of cinematic sound, if not before” (15). These national, even local spaces, often bundled together in a rather simplistic manner as “peripheral or dependent cinemas” (the terms are Paranaguá’s) nonetheless constitute a source of diversity and plurality which is unfortunately often reduced to a merely rhetorical value, as if the relative dearth of communication and collaboration could be remedied by appealing to some vague, oft-repeated principle of “difference” which scarcely leaves a mark on the hegemony of the long-standing, quasi-naturalized distinction—or, better yet, opposition—between Hollywood commercial and European “high-art” ventures. This distinction, so critical to those who take binary formulations (commerce/art, Hollywood/Europe, frivolity/seriousness, convention/experimentation, and so on) as a privileged point of departure for critical analyses in which value judgments are in many respects already implicit, is itself deceptive inasmuch as it blurs, even erases, differences within the United States, collapsed into Hollywood, let alone within Europe. After all, “European cinema,” long and loosely conceived as the great option to the Hollywood business machine (which is itself less coherent and unified as many would like to believe), is far from being a coherent and unified totality, regardless of how many international co-productions there may be within the European Union.

Of course, Europe is not always simply Europe, for within it, Spanish and Portuguese cinema, or cinema in Spanish and Portuguese (let alone in Catalan, Galician, and Basque), has historically not enjoyed the same appreciation and visibility as French, German, Italian, or British cinema and has entered the pantheon of high cinematic art thanks to a handful of filmmakers who, deemed to be “geniuses” of “universal” stature (Luis Buñuel, who worked on both sides of the Atlantic, is here paradigmatic), stand as the luminous exceptions to a putative, and rather somber, general rule. In more than one history of European cinema, as in more than one history of European art and literature, Spain and Portugal are either all but absent or figure only as exceptional or peripheral. In saying this I do not mean to suggest that Spanish and Portuguese cinema, much less some rather vague Iberian cinema, is analogous, without qualification, to Latin American cinema (or even that there is an Iberian or Latin American cinema). Rather, my point is that on both sides of the Atlantic, albeit to undoubtedly different degrees, one encounters a certain weary familiarity with marginalization—as well as with the more material challenges of securing funding for works that rarely have the ready-made box-office draw of Hollywood blockbusters (or, for that matter, many English-language “independent” films), and that rarely have the “ready-made” cultural clout of French, British, Italian, or German productions. Beyond the sense of a shared linguistic culture (Portugal and Brazil, Spain and Spanish-speaking America), other situations and experiences, profoundly marked by the vagaries of the global market, are also shared, even though problems of marginalization and funding have historically been generally more acute in Latin America than in Spain, where things have hardly been easy.

As important as protectionist measures and public subsidies may be, as concerted and effective as the policies of promotion of any given national or pan-national culture may appear, the cinema is, in its material and technical aspects, a phenomenon of global, universal, international and/or multinational dimensions (the last four adjectives are not, by the way, mere synonyms). With respect to Latin America, Paranaguá, once more, signals not just “the importation of films to nourish new spectacles” but also “the importation of machinery and technology [which] is common to exhibition as well as production. In spite of a few unsuccessful projects, ‘virgin’ film stock, the negatives as well as the material needed to make copies, always had to be imported” (28). For the Brazilian critic, the reality of “importation” is part and parcel of a relation of dependence which renders comparative approaches as complicated as they are urgent. From a somewhat different perspective, Cuban critic Luciano Castillo—who, unlike Paranaguá, does not translate material dependency in terms of “productive” and “vegetative” cinematic practices—grapples with the material conditions of technology that make the “seventh art” one of the most costly and demanding of all (of the arts, only architecture—and even then, not always—outstrips it):

The last decade of the Siglo de Lumière for Cuban cinema was by no means untouched by the economic restrictions imposed on the country during the so-called “Special Period.” The German Democratic Republic, which had traditionally supplied filmic material, collapsed as abruptly as the sadly famous Berlin wall, dragging in its wake the entire socialist block in a process that had hitherto been unimaginable. It constituted the coup de grâce for Cuban documentary cinema which found an alternative of shorts in the guise of video—a veritable “challenge for the future”, according to Alfredo Guevara, founder of the ICAIC [Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry]—, though without reaching the level of production and the achievements that had been so admired in other moments. The “art of our time” requires copious resources and, above all, the ability to enjoy the international distribution that offsets costs and contributes to self-financing. Coproductions with European countries became for Cuba—as for the rest of Latin America—an unavoidable option: to coproduce or not to produce, such is the very un-Shakespearean dilemma in which our cinemas find themselves in times of globalization (21).

I have taken the liberty of citing Castillo so extensively because what he says here, in his beautifully argued book A contraluz [Santiago de Cuba: Editorial Oriente, 2005], helped both to frame and to model the symposium on new technologies and new narratives. The “art of our time,” emblem of modernity, does not just require copious resources and networks of international distribution but also transnational cooperation. Accordingly, it raises important questions about what we understand by “our time,” especially since both the “our,” or “we,” and the time or times to which the plural pronoun is attached reveal themselves, over and again, to be sundered and atomized in a world in which solidarity is far from being a global reality.

Along with techno-material questions about resources, productions, and products, and socio-symbolic questions about cooperation, dialogue, solidarity or the lack thereof, there are, of course, questions about artistic and political experimentation, innovation, and adaptation which are at play in the very notion of a “challenge for the future” and, more concretely, the turn to “alternatives,” here in the form of video. These alternatives, and their bearing on the cinema (so-called alternative or experimental ventures definitely included), comprised one of the themes of the symposium in Spain and will surely figure in the upcoming symposium on the uses of history in a cinematic context. Challenges for the future, creative alternatives, resources, collaborations, and networks of production and distribution, all of this and much more has been dizzyingly complicated in the face of growing, and seemingly unstoppable, processes of digitalization and the progressive eclipse of celluloid. The eclipse of celluloid, along with its ontological charge of luminous traces of real objects and subjects, is unsettling for many (it would be interesting, that is to say unsettling, to imagine a new “Morel’s invention” based on digitalization), but it is also, for many others, exciting (I confess that, for me, it is at once unsettling and exciting), especially inasmuch as resources and products proliferate, diversify, and in some cases free themselves from the heavy dependency on bulkier, more expensive technologies. The video “alternative” that Castillo mentions, and that is expanded in turn by yet other alternatives in other formats (some of which are as small, mobile, and relatively affordable as the cellular phone), entails possibilities of a very different sort: for instance, a cinematic practice that is less white, less masculine, less heterosexual, less wealthy, and less directly implicated in, and dependent on, the so-called First World. For it is worth remembering that alongside the global predominance of Hollywood, indeed as a constitutive feature of it, stands the predominance of a certain gender, race, class, and sexuality. Mexican filmmaker Juan Mora Catlett points to something similar, I submit, when he refers to “the facilities that working in digital modalities entails,” facilities that include not just the “multi-camera” or “simultaneous use of various cameras” but also “the possibility of working [as in his Eréndira ikikunari] with a group of indigenous people instead of professional actors” and, moreover, of working in their language, in this case P’urhépecha, rather than in Spanish.

Although the progressive disappearance of celluloid (and by extension, of a certain indexicality or referential capacity) and of large screening venues (and by extension, of a certain shared “theatrical” experience), and the concurrent rise of digitalization and “private entertainment centers” constituted one of the principal axes of our gathering in Cuenca and Madrid, the symposium also strove to take into consideration a variety of innovations and alternatives—from video to the Internet, cyberspace, blogs, cell phones, and other interactive technologies—that in many respects question the very concept of “cinema.” Similar questions obtain for “narrative”—often derided as such in more self-consciously experimental ventures— which undergoes any number of modifications in phenomena such as video-art and video-dance. Whatever the case, profound and far-reaching changes in the industry of cinema and in the very tools and procedures of filmmaking are affecting, often in still unforeseeable ways, the formal contents and discourses of authorship (the auteur tradition with its fetishized emphasis on the personal style and signature of the director as artist) as well as the very figure of the auteur, often displaced by actors, producers, distributors, and an array of business people, but also reconfigured, if not “democratized,” as new, less costly devices become accessible to a larger number of people. The proliferation of new audiovisual technologies raises, in short, not just challenges for the future but also possibilities for different and revitalized understandings and practices of transnational cinema beyond an exclusively or even predominately European or North American framework. Ibero-American cinema, however fraught with—and enriched by—national, regional, and local particularities, remains, as it were, under construction, its building blocks perhaps only now emerging.

Fall 2009, Volume VIII, Number 3

Brad Epps is Professor of Romance Languages and Literatures and Chair of the Committee on Studies of Women, Gender, and Sexuality at Harvard University. He also co-directs, with Haden Guest, the Committee on Ibero-American Film at the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies. His most recent book is All About Almodóvar: A Passion for Cinema (University of Minnesota Press, 2009).

Related Articles

Coconut Milk in Coca Cola Bottles

Common knowledge has it that virtually any movie, once removed from its original cultural context of production and reception, might be either misunderstood and misperceived or re-interpreted and re-signified. Likewise, we may agree that national cinemas seek to define, challenge….

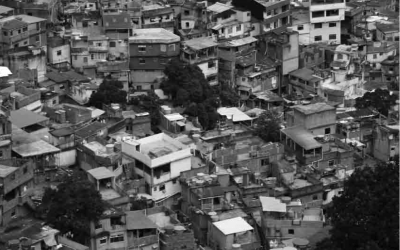

Neither the Sertão or the Favela

To frame the poetics of the ordinary in terms of subtlety and delicateness is to propose an antidote both for cynicism and for what I call Neo-Naturalism. Its appearance, at least in Brazilian cinema and literature, has been clearly identified, ranging from peripheral subjects…

Brazilian Cinema Now

Snow falling in the city of São Paulo, in southern Brazil? Taking a helicopter in São Paulo then arriving a few moments later in the deep wilderness of the Amazon jungle, half a continent further away to the north? Then meeting a white Asian tiger in the heart of the Amazon forest?…