From Barracks to Museum

The Intersection of Memory and Forgetting

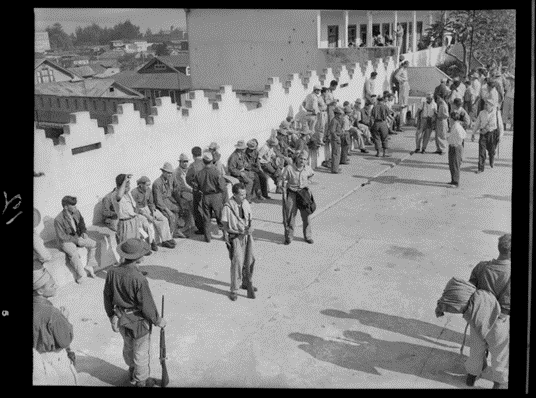

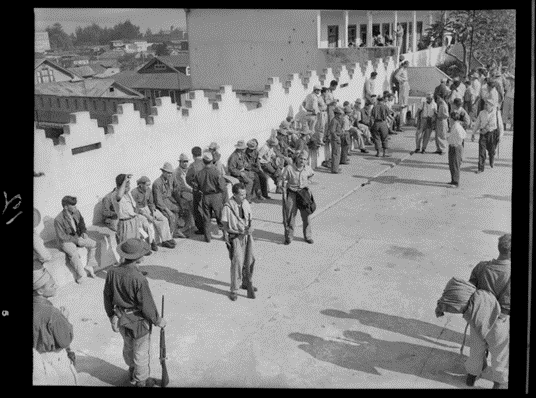

Soldiers during the Cardonazo photographed by Mario Roa (Roa Gutiérrez family collection).

The former Bellavista Barracks, the main headquarters of the National Museum since 1949, has been a witness, protagonista and symbol of Costa Rican history, not only because of its physical presence, but because of the imaginaries with which it is associated. The building is an undeniable reference to the symbolic act of the abolition of the army, when José Figueres Ferrer, the winner of the 1948 civil war and de facto president of the Founding Junta of the Second Republic, swung a sledgehammer against one of the barrack’s battlements on December 1, 1948.

I want to share a bit of the behind-the-scenes of what French historian Pierre Nora called “places of memory, underlining the dichotomy around a basic element of the Costa Rican imaginary: peace, where the other side of the coin, violence, stands out for its “strident” silence, as exemplified by the symbolism of Bellavista.

In the last renovation of the exhibit “From Barracks to Museum,” the narrative constructed through space, images and words has gone beyond the abolition of the army in 1949.

Besides the recognition of the importance of the abolition of the army for the subsequent development of a civilist society, any historical interpretation of the 1940s would be only a partial analysis if it did not also make visible the ideological conflict, the violence, repression, persecution and death before, during and after the 1948 Civil War.

The painful wounds of this era are woven together with the memories, forgetting and symbols of the victors, although the voices of the defeated and silenced after the 1948 conflict have not disappeared. Such was the impact of this era that it marked Costa Rican’s political loyalties during a good part of the 20th century.

Imges Speak Louder than Words

On December 1, 1948, a parade of students and soldiers was accompanied by speeches and the symbolic hammer blow in Bellavista’s central patio. At the same time, the Public Security Minister Edgar Cardona gave the keys of the building to Education Minister Uladislao Gámez in a symbolic gesture of the building’s new role as the headquarters of the National Museum.

In May 1948, Museum Director Juvenal Valerio asked the Founding Junta to use the barracks to house the National Museum. In April 1949, however, months after the symbolic act of abolition, Edgar Cardona—the same person who in November had proposed the abolition of the army—would become the leader of the “Cardonazo,” an attempted coup against Figueres Ferrer. It was not until after this uprising that the National Museum began its transfer to the new barracks headquarters.

Several photos still exist of the December 1 events in the barracks, although the most iconic one is the tumbling of the battlement (which had previously been loosened) with Figueres Ferrer’s sledgehammer blow; the exact moment was captured by photojournalist Mario Roa Velásquez (1917-2004). It is not a coincidence that the Journalists’ Union photojournalism prize now bears his name.

The exhibit, “From Barracks to Museum,” seeks to share with the public the history of the origin, transformation and use of the building as barracks, its subsequent life as a museum and also its role as a reference point in the capital city. Nevertheless, in the past two years, the exposition has been strengthened by a new focus, above all, with images that have never been displayed before.

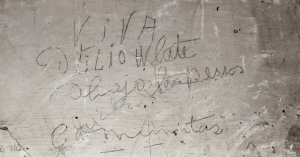

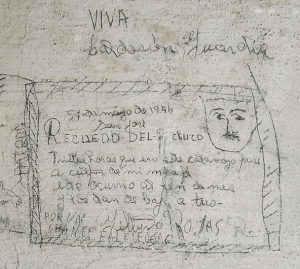

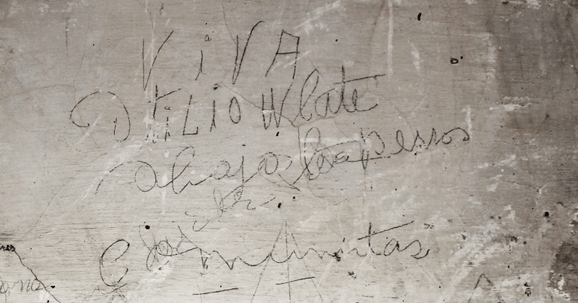

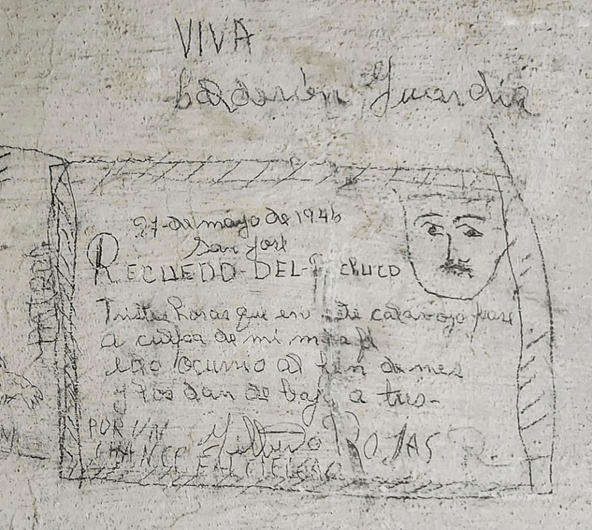

In terms of physical space, the exhibition reopened the prison cells with their original graffiti from the 1940s (especially 1948) to the public and enabled access to the southeast tower, whose upper part was demolished by the government in 1949 before the building became the museum. Four sections of the exhibition were defined: a brief context of the history of the army in Costa Rica, the historical trajectory of the National Museum since its founding in 1887, as well as the different patrimonies found nowadays throughout the institution.

- Grafitti en las celdas del antiguo Bellavista (Museo Nacional de Costa Rica).

- Grafitti en las celdas del antiguo Bellavista (Museo Nacional de Costa Rica).

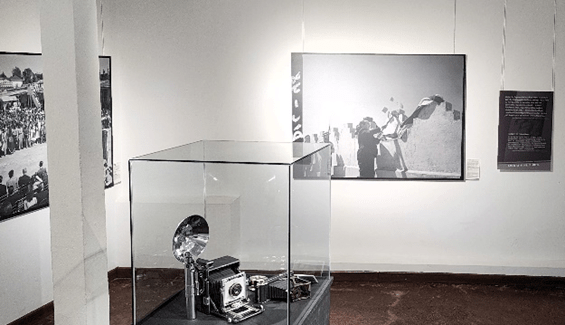

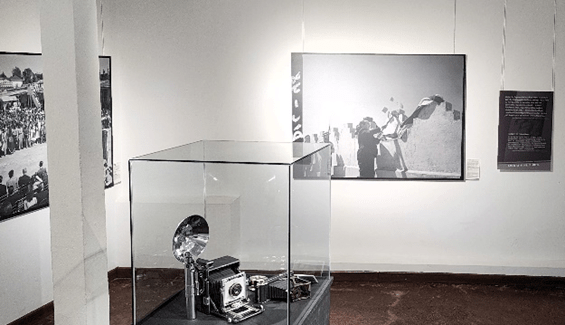

The fourth section, the greatest novelty, features previously unpublished material found in the photographic archives of Mario Roa, in the custody of his heirs, who also loaned the museum the original camera with which Roa took the iconic December 1, 1948, photograph.

Mario Roa’s camera and photograph of the act of symbolic abolition (National Museum of Costa Rica).

The Roa family granted permission to the National Museum to reproduce the most well-known photos of that day from the original negatives: the sledgehammer blow and the public gathered in the central patio during the event. In the revision made of the negatives preserved by the family, I found several unpublished photos of the Bellavista Barracks. This material was reproduced in large format, respecting the frame of the negatives and Roa’s notes. The material was displayed in an exclusive space dedicated to the photographs.

One striking image stands out among the others: the photograph of a dead person in the Bellavista Barracks during the April 1949 “Cardonazo.” As a curator and historian in the National Museum of Costa Rica for more than 25 years, I found it very special to find this photograph, a needle in the haystack. It was the first time I witnessed in such an explicit form the face of death from that era.

Victim who died during the Cardonazo of 1949, photographed by Mario Roa (Roa Gutiérrez Family Collection).

It is not an accident that one of the most sensitive gaps in historical information is still the lack of knowledge about the deaths from 1940s—and especially from the 1948 Civil War. The statistics cited (still without any in-depth study) range from 500 to 4,000 deaths.

Who was the person portrayed in Roa’s photograph? We are still not sure. A similar question was called to memory fifty years after the Civil War by two brothers whose childhood was intertwined with the 1940s. Their story, included in the current exhibit, was taken from narratives first presented in a 1998 contest organized by the Universidad de Costa Rica with the title “Children from ’48 write.”

These two young people, children of a military musician, also saw the less amiable face of the old barracks. Here is part of their story:

Here was Bellavista!… We went through the main entrance, no guard questioned our presence, it was posible we were the only children there that day, at least at that moment. We crossed into the interior part of the building and reached the hallway in front of the barrack’s main patio.

Our eyes immediately focused on images that have always stayed with us because the patio was covered with many bodies of men, some face up, others with their faces against the floor, there are hard gazes, diverse expressions on their pale faces and they are wearing a variety of clothes. Who were they?

Cells of the old Bellavista Barracks (National Museum of Costa Rica).

In the face of the profound historical silence about the violence and death of the era, it was very important that the public see in the exhibit, face to face, at least one image of the deaths in that period, with the best quality possible in large format. This image was placed on the wall in front of the famous photo marking the abolition of the army, and between them, the camera of Mario Roa, who made both photographs.

I’ve witnessed the impact of this photo on many visitors. Some older people remember stories that their grandparents or parents told them about the war. Younger visitors admit they know little about the violence experienced in Costa Rica in the mid-20th century. Foreigners find it difficult to understand how a society can function without an army.

A Place of Memories

Before the museum moved to the building, the government demolished the barrack’s most strategic tower (the southeastern one) to prevent the building’s use in another military conflict. It also closed off the internal tunnels and tore down several outside walls. During the 50s, the museum also put a neocolonial architectural stamp on the building’s interior, accompanied by the demolition of the battlement associated with the famous sledgehammer of the abolition announcement, actions that bit by bit stripped away the building’s own history.

During the 80s, the former barracks had another discursive meaning: that of peace and democracy. These were years marked by the Cold War, guerrillas in the rest of Central America and the awarding of the 1987 Nobel Peace Prize to former President Oscar Arias Sánchez.

During his government, public institutions, tractors and workers labored feverishly to finish the Plaza of Democracy in front of the museum. Its name was chosen in honor of the anniversary of a hundred years of Costa Rican democracy. The goal was to have it ready in time for the Summit of Hemispheric Presidents in 1989.

This spatial transformation and symbolic reshaping of meaning was polemical; several old houses that were still inhabited were torn down and historians questioned with reason whether one could talk about a hundred years of Costa Rican democracy. Moreover, during the building’s remodeling, several bullet holes from the 1932 “Bellavistazo” and the 1949 “Cardonazo” were plastered over. This led to intense public discussion that guaranteed that such vestiges would no longer be covered over.

From thos decade on, the official commemoration of the abolition of the army took on new relevance. A key promoter was the Quaker organization, Friends Center for Peace, whose acts of commemoration of December 1 usually involved the participation of veterans of the 1948 civil war, especially those who had served in the National Liberation Army headed by Figueres Ferrer.

The very close relationship between the Bellavista Barracks and the figure of Don Pepe—as many affectionately called him— meant that when he died in 1990, thousands of Costa Rican attended his wake at the National Museum to say a final goodbye.

Years later, in the context of the 50-year anniversary of the 1948 Civil War, the creation of a monument to him in the Plaza of Democracy was promoted, with much support from his relatives. The well-known artist Marisel Jiménez created the sculpture in bronze, inspired by Don Pepe’s saying, “why tractors without violins.” The statue was inaugurated in 1998.

Looking in the Mirror

In 1998, another parallel history was beginning to be constructed, since the space where the exhibit “From Barracks to Museum” stands today was beginning a process of recuperation of the building’s historical memory, as part of a staff initiative. In the light of the 50-year commemoration of the civil war, it was decided to recuperate the most original traces of the barrack’s interior on the bottom level of the building’s south side: the area of the kitchen, toilet stalls, baths and prison cells.

This area had been modified first into an exhibition space for religious art and then in the 90s as a storage room for collections. In the process, museum restorers recuperated structures and original artefacts as part of the floors and original toilets , cleaning them and conserving the original graffitis from the 40s that had never been seen by the museum’s visitors.

The recuperation of this original architectual structure took another great step forward in 2009, in the context of making an accesible entrance on the west side of the building, where part of the structure of the old tunnels was stumbled upon unexpectedly; only a small segment had been excavated by the museum’s archaeologists, not because of a lack of will, but time and money.

In the future, the continuation of the scientific excavation of these tunnels will be key to giving new meaning to the old barracks. It’s necessary to keep widening the discusión about both sides of the coin of the historic significance of the old Bellavista Barracks which, thus, will lead us to wider interpretations of one of the most complex periods of 20th-century Costa Rican history.

Gabriela Villalobos is the historian and curator at the National Museum of Costa Rica.

De Cuartel a Museo

Intersección de Memorias y Olvidos

Por Gabriela Villalobos

Soldados durante el Cardonazo fotografiados por Mario Roa (Colección familia Roa Gutiérrez).

El antiguo Cuartel Bellavista, sede principal del Museo Nacional desde 1949, ha sido un testigo, protagonista y símbolo de la historia de Costa Rica, no solo por su materialidad, sino también por los imaginarios a los que se encuentra asociado. El edificio es un referente innegable del acto simbólico de abolición del ejército un 1º de diciembre de 1948, cuando José Figueres Ferrer, vencedor de la guerra civil de 1948 y presidente del gobierno de facto de la Junta Fundadora de la Segunda República, da un mazazo a una de las almenas del cuartel.

Lo anterior, nos conduce a interactuar con ese concepto que el historiador francés Pierre Nora llamó “los lugares de la memoria”, resaltando la dicotomía alrededor de un elemento básico del imaginario costarricense: la paz, donde la contracara, la violencia, destaca por su “estridente” silencio, como bien lo ejemplifica el devenir del simbolismo del Bellavista.

En la última renovación de la exhibición “De Cuartel a Museo” se ha procurado que la narrativa construida mediante el espacio, las imágenes y las palabras no se reduzca solo a la abolición simbólica del ejército el 1º. de diciembre de 1948.

Cualquier interpretación histórica de la década de 1940, además de reconocer la importancia de la abolición para el posterior desarrollo de una sociedad civilista, sería un análisis a medias si no se visibiliza también la conflictividad ideológica, la violencia, represión, persecución y muerte antes, durante y después de la Guerra Civil de 1948.

Las dolorosas heridas de esa época se entrelazaron con las memorias, olvidos y símbolos de los vencedores, sin que desaparecieran las voces de los vencidos y silenciados después del conflicto de 1948. Tal fue el impacto de esa época, que marcaron las lealtades políticas de los costarricenses durante buena parte de la segunda mitad del siglo XX.

Imágenes Que Dicen Más Que Palabras

El 1º de diciembre de 1948, el desfile de estudiantes y de soldados se acompañó de discursos y del simbólico mazazo en el patio central del Bellavista, también se hizo la entrega simbólica de las llaves del edificio por parte del Ministro de Seguridad Pública Edgar Cardona al Ministro de Educación, Uladislao Gámez, para que pasara a ser la sede del Museo Nacional.

El traspaso del Cuartel para ser usado por el Museo Nacional había sido solicitado a la Junta Fundadora desde mayo de 1948 por el director del Museo, Juvenal Valerio. Además, meses después del acto simbólico de abolición, Edgar Cardona—el mismo que en noviembre había propuesto la supresión del ejército-, pasará en abril de 1949 a ser el líder del “Cardonazo”, un intento de golpe de estado contra Figueres Ferrer. Será hasta finales de ese que el Museo Nacional comenzó su traslado al Cuartel.

Del acto del 1º. de diciembre en el Cuartel hay varias fotografías, aunque lo cierto es que la icónica imagen de la almena del Cuartel cayendo (previamente aflojada) por el mazazo dado por Figueres Ferrer es la principal que ha pasado a la historia; momento exacto capturado por el fotoperiodista Mario Roa Velásquez (1917-2004). No es casual que el actual premio de fotoperiodismo del Colegio de Periodista lleve su nombre.

La exhibición “De Cuartel a Museo” ha buscado compartir con el público la historia del origen, transformación y uso del edificio como cuartel, su paso a museo y también su devenir como hito de la ciudad capital. No obstante, la propuesta expositiva de estos dos últimos años se nutre de nuevos enfoques, y, ante todo, de imágenes inéditas.

En términos espaciales, en la exhibición se volvió a abrir al público las celdas con grafitis originales de la década de 1940 (especialmente de 1948) y se habilitó el acceso al torreón suroeste, cuya parte superior fue demolida por el gobierno en 1949 antes del traspaso del edificio al Museo. También se definieron mejor cuatro secciones: un breve contexto de la historia del ejército en Costa Rica, el devenir histórico del Museo Nacional fundado en 1887, así como los distintos patrimonios a los cuales se encuentra enlazado el actual accionar de la institución.

- Grafitti en las celdas del antiguo Bellavista (Museo Nacional de Costa Rica).

- Grafitti en las celdas del antiguo Bellavista (Museo Nacional de Costa Rica).

La cuarta sección, la mayor novedad, se nutre del material inédito encontrado en los archivos fotográficos de Mario Roa, custodiado por sus descendientes, quienes además prestaron a la institución para su exhibición la cámara original con la que Roa tomó la icónica fotografía del 1º de diciembre de 1948.

Cámara de Mario Roa y fotografía del acto de abolición simbólica (Museo Nacional de Costa Rica).

La familia Roa autorizó al Museo Nacional reproducir a partir de los negativos originales las fotografías más conocidas de ese día: el mazazo y el público congregado en el patio central durante el acto. En la revisión que realicé de los negativos conservados por la familia encontré varias fotografías inéditas del Cuartel Bellavista. Ese material se reprodujo en gran formato respetando el marco de los negativos y las anotaciones de Roa, por lo cual se dedicó un espacio exclusivo de la exhibición a dicha fotografías.

Del conjunto inédito destaca una imagen impactante: la fotografía de una persona muerta en el Cuartel Bellavista durante el “Cardonazo” de abril de 1949. Como curadora e historiadora del Museo Nacional de Costa Rica por más de 25 años, fue muy particular encontrar esa fotografía, una aguja en un pajar. Era la primera vez que veía de forma tan explícita el rostro de la muerte en esa época.

Fallecido durante el Cardonazo de 1949, fotografiado por Mario Roa (Colección familia Roa Gutiérrez).

No es casual que uno de los vacíos de información histórica más sensibles siga siendo el desconocimiento de los muertos de la década de 1940 y en especial de la Guerra Civil de 1948: las cifras reseñadas (todavía sin estudios a profundidad) hablan desde los 500 hasta los 4000 muertos.

¿Quién fue el retratado? Todavía no lo sabemos con certeza. Similar pregunta también fue rememorada cincuenta años después de la guerra civil por dos hermanos cuya infancia está ligada la década de 1940. Su relato, se volvió a incluir en la actual exhibición, el cual fue tomado de las narraciones del concurso que en 1998 organizó la Universidad de Costa Rica bajo el título “Niñas y niños del 48 escriben”.

Estos dos niños, hijos de un músico militar, también vieron la cara menos amable del antiguo Cuartel. Aquí está parte de su relato:

¡Era el Bellavista!… Atravesamos la entrada principal, ningún guardián cuestionó nuestra presencia, éramos posiblemente los únicos niños ese día al menos en ese momento. Avanzamos hacia el interior del edificio y nos dejaron de pie en el pasillo frente al patio central del cuartel…

Nuestros ojos de inmediato enfocaron imágenes imperecederas en nosotros pues ese patio estaba cubierto por muchos cuerpos de hombres fallecidos boca arriba unos, otros con el rostro contra el suelo, son sus duras miradas, diversas expresiones en los pálidos rostros y con diferentes vestiduras. ¿Quiénes eran?

Celdas del antiguo Cuartel Bellavista (Museo Nacional de Costa Rica).

Ante al profundo silencio histórico sobre la violencia y muerte de la época, fue muy importante que en el a exhibición el público viera, cara a cara, en su máxima calidad y en gran formato la fotografía de al menos, uno de los muertos de ese período. Esta imagen fue colocaba en la pared del frente de la famosa fotografía de la abolición; en el medio la cámara de Mario Roa, autor de ambas fotografías.

He sido testigo del impacto que causa esta fotografía en muchos visitantes de la exhibición. Algunos de mayor edad rememoran historias que les contaron sus abuelos o padres sobre la guerra. Los de menor edad admiten lo poco que conocen sobre la violencia que vivió el país a mediados del siglo XX. Para los extranjeros es difícil comprender como funciona una sociedad sin ejército.

Un Lugar de Memorias

Antes del traspaso del edificio al Museo, para evitar que el edificio fuera usado en otro conflicto militar, el gobierno en 1949 demolió el torreón más estratégico (el suroeste) del Cuartel, cerró los túneles internos y demolió varios muros externos. Durante la década de 1950 el Museo además impregnó con un discurso arquitectónico neocolonial el interior del edificio, lo que se acompañó de la demolición de la almena asociada al mazazo de la abolición; acciones que poco a poco despojaron al edificio de parte de su propia historia.

Durante la década de los ochenta el simbolismo del Cuartel tuvo también a otro protagonista discursivo: lo de la paz y la democracia. Años marcados por la Guerra Fría, las guerrillas en otras países de Centroamérica y la obtención del Nobel de la Paz en 1987 por parte del expresidente Oscar Arias Sánchez.

Durante su gobierno, instituciones públicas, tractores y obreros trabajaban a ritmo de tambor para finalizar la plaza de la Democracia frente al museo. Su nombre fue en un honor del centenario de la democracia costarricense. La meta era tenerla lista para la Cumbre de presidentes del hemisferio de 1989.

Esa transformación espacial y resignificación simbólica se acompañó de la polémica: se demolieron antiguas casas todavía habitadas y los historiadores cuestionaron con fundamento por qué no se podía hablar del centenario de la democracia costarricense. Además, durante la remodelación del edificio se repellaron impactos de balas del “Bellavistazo” de 1932 y del “Cardonazo” de 1949; eso conllevó una intensa discusión pública que evitó que se continuara tapando dichos vestigios.

Será a partir de esa década que la conmemoración oficial de la abolición del ejército fue adquiriendo mayor relevancia. Una promotora clave fue la organización cuáquera llamada Centro de Amigos para la Paz, cuyos actos conmemorativos del 1º de diciembre generalmente contaban con la participación de ex combatientes de la guerra civil de 1948, ante todo de quienes habían formado parte del ejército de Liberación Nacional liderado por Figueres Ferrer.

La relación tan estrecha del Cuartel Bellavista y la figura de José Figueres Ferrer implicó, que, cuando en 1990 murió Don Pepe, como mucho la llamaban con aprecio, miles de costarricenses llegaron a darle el último adiós y a velar su cuerpo en las instalaciones del Museo Nacional.

Años después, en el contexto del cincuentenario de la Guerra Civil de 1948, también se impulsó, con importante apoyo de sus familiares, la creación de un monumento a Figueres para ser ubicado en la plaza de la Democracia. La reconocida artista Marisel Jiménez creó un conjunto escultórico en bronce, inspirada en la frase de Don Pepe “para qué tractores sin violines.” El monumento fue inaugurado en 1998.

La Mirada Frente al Espejo

En 1998 también se comenzó a construir otra historia paralela, pues el espacio donde hoy está la exhibición “De Cuartel a Museo” también experimentó un proceso de recuperación de la memoria histórica del edificio impulsada a lo interno de la institución. Asimismo, en miras de la conmemoración del cincuentenario de la Guerra Civil de 1948, se decidió recuperar las huellas más originales del interior del cuartel ubicadas en el nivel inferior de la parte sur del edificio: el sector de la cocina, los retretes, los baños y las celdas.

Este sector había sido modificado en función de la antigua sala de arte religioso y en los noventa estaba siendo utilizado para el depósito de colecciones. En el proceso, los restauradores del Museo recuperaron estructuras y huellas originales, como parte de los pisos y los antiguos retretes del cuartel, así como también limpiaron y estabilizaron los grafitis originales la década de 1940 que nunca habían sido visto por el público visitante.

La recuperación de ese tejido arquitectónico original tuvo otro gran paso cuando en el 2009, en el contexto de habilitar una entrada con accesibilidad universal por la fachada oeste, se encontró de manera inesperada parte de la estructura de uno de los antiguos túneles, solo un pequeño sector fue excavado por arqueólogos de la institución, no por falta de voluntad, sino de recursos y tiempo.

En el futuro, continuar la excavación científica de esos túneles será clave para la resignificación del antiguo cuartel. Es fundamental seguir ampliando la discusión sobre las ambas caras de la moneda del significado histórico del antiguo Cuartel Bellavista, que, por ende, nos conducirá a relecturas más amplias sobre uno de los períodos más complejos de la Costa Rica del siglo XX.

Gabriela Villalobos es la historiadora y curadora del Museo Nacional de Costa Rica.

Related Articles

A Review of Alberto Edwards: Profeta de la dictadura en Chile by Rafael Sagredo Baeza

Chile is often cited as a country of strong democratic traditions and institutions. They can be broken, however, as shown by the notorious civil-military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet (1973-1990). And yet, even a cursory view of the nation’s history shows persistent authoritarian tendencies.

Homecoming and Public Education: The Cancel Culture (of class time) in Costa Rica

When I returned home on my sabbatical, I couldn’t stop thinking about Svetlana Boym’s extraordinary book, El futuro de la nostalgia.

Crisis of Citizen Insecurity in Costa Rica: A Challenge to the Model of Demilitarized Democracy

I began my political and public service career thirty years ago as Minister of Public Security, the first woman to ever hold that post in my country, Costa Rica.