From Favela to Bairro

Rio’s Neighborhoods in Transition

The Brazilian firm of Jorge Mario J¡uregui Architects is the first Latin American recipient of the Harvard Graduate School of Design’s Veronica Rudge Green Award in Urban Design. The award, given for outstanding accomplishments that make positive, humane contributions to urban life, recognized the architecture firm for its efforts to improve the poor neighborhoods of Rio de Janeiro.

“There is a general perception of the betterment of living conditions for the shantytown and its relation to the city,” said J¡uregui, a long-time Brazilian resident originally from Argentina, in an interview.

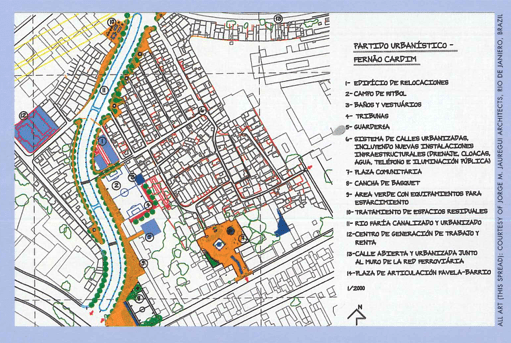

Public spaces are at the heart of J¡uregui’s designs — including the construction of community centers to provide recreational activities, job training, and assistance in setting up businesses in these shantytowns, known as favelas. Private spaces are left undisturbed unless a structure is substandard or sitting on unstable land. Relocation units are erected elsewhere in the favela for residents whose housing must be torn down.

At the award ceremony, J¡uregui noted that the favelas of Rio have long been considered a problem. Unlike similar marginalized neighborhoods in other cities, many of these shantytowns share prime space with the city. People who live near the favelas would like to see them torn down and their residents relocated out of sight. The residents themselves often live in substandard housing; there is no clean water and no trash pickup. In many cases people have jerryrigged electrical wires to bring electricity into their homes. The people are poor, uneducated, and since the 1980s, the areas have been a haven for drug traffickers and corrupt policing.

Ben Penglase, a Ph.D. candidate in Social Anthropology at Harvard, indicated that about a fifth of Rio’s population live in favelas; one out of every three homes is located in these poor neighborhoods. Faced with these statistics, the City of Rio decided to take action. In the 1990s, it designed Favela Bairro, a program that turns an impoverished neighborhood into a functioning one, integrated with the city at its edge. The city created a Housing Secretariat to oversee the project, and the City of Rio, the Inter-American Development Bank, and the European Union provide funding.

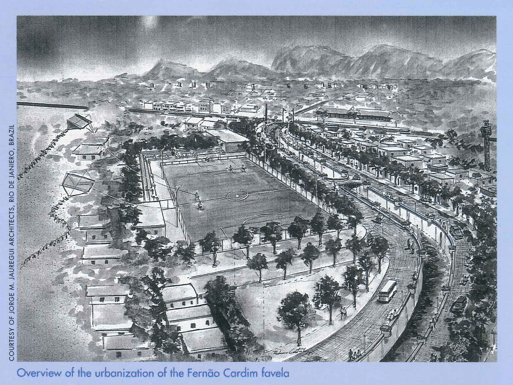

General aerial view of the Fernāo Cardim urbanization.

The large-scale ongoing project involves teams of architects, engineers, construction workers, social workers, psychologists, and the people of the favelas themselves. According to the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD), these extraordinary undertakings, called interventions, differ from other architectural interventions in the 1960s and 1970s, which razed favelas and moved people out to government housing elsewhere. Favela Bairro works instead with existing physical and social structures to create improved conditions that will complement the physical and social fabric that grew from people living in such proximity to each other. Many times these favelas are home to generations of the same family. Relocating them disrupts their already adverse lives, removing them from longstanding social ties and jobs.

Rodolfo Machado, Harvard GSD professor in the Practice of Architecture and Urban Design and chair of the award committee, wrote about Jáuregui’s work, commenting on the distinction in Rio between the ‘formal city’ — where the middle class lives, and the ‘informal city’ — the favela. J¡uregui, he says, works to “erase that opposition by creating true neighborhoods where there are streets with names, numbers on the houses, driveable streets with underground infrastructure, and well established pedestrian paths leading to social centers or public plazas and recreational spaces.” He cites the characteristics of this project that set it apart from previous architectural interventions: the project starts with each favela’s particular characteristics, the team shows respect and kindness for the inhabitants of the favelas, and the architecture serves a “social purpose resulting from local circumstances.” “A simple design”, Machado wrote, but “a sophisticated impact.”

While the project in each favela takes on a slightly different look, several components remain constant across neighborhoods. Paths are paved to provide thoroughfares through the favela which link up with streets of the ‘formal’ city, giving residents better access into and out of the city and their neighborhood. The teams construct a sewage system and establish trash pick up, they build a day care center, and they improve the all important soccer field.

Before beginning the physical work, J¡uregui and his team spend time with residents to find out what they would like to see changed and to offer ideas that remedy the issues raised. He said that residents are always amazed to see his drawings of what could be. “In almost all cases, the first ideas I take into the meetings, the renderings and perspectives of what it would look like, are much more than they have ever expected to have in their favelas.”

During the award ceremony, J¡uregui highlighted the work he has done in five favelas, which range in size from 850 to 12,000 inhabitants: Fuba-Campinho, Salgueiro, Vidigal, Fernão Cardim, and Rio das Pedras. He remarked on the unique landscape of Rio, where the hills form the cityscape rather than the buildings. The shantytowns have been built on these hills, he said, “wherever space is available, so there are no streets. It’s a very compact tissue. The most difficult thing is to trace and define those areas where roads and pedestrian pathways are going to be built.”

The work can take up to 18 months to complete. Afterwards, the teams get a sense of how the residents feel about the improvements. “There seems to be a strong relationship between these interventions and the reduction of crime, drug dealing, etc.,” J¡uregui noted. The city also hires a firm to formally poll the residents on the various aspects of the intervention, although there are not yet any studies to show the work’s long-term impact.

Penglase, who lived in a favela in Rio’s Zona Norte for almost a year, has a different perspective on favelas — he sees them as a solution rather than a problem. “They are the answer that the urban poor of Rio de Janeiro found to the dilemma of being caught between the high cost of housing and transportation on the one hand, and low wages and a lack of sufficient full time employment on the other,” Penglase stated. “It would be hard to imagine a more grass-roots initiative to the problem of a lack of adequate urban housing.”

He commended Favela Bairro for the positive change it signals. “There is a change in the attitude of officials. There is now acceptance of these neighborhoods. Favelas are there to stay; they cannot be eradicated or ignored.” But he is careful in gauging the long-term success of the project. “Of course improving water and sewage makes a huge difference in the community,” he said. “But these communities aren’t just a result of a lack of city services. They are the result of social and economic inequalities in Brazil. Favela-Bairro is just one of a series of steps that has to happen.” He cited the social programs — income generation, childcare, sports programs, and health care — that must be maintained. “These are the really important part of Favela Bairro.”

Scaled plan of favela Ferñao Cardim, Rio de Jainero, Brazil.

Ironically, he feels the improvements could also harm the residents. When you fix things like the roads and paint the houses, he said, “when you remove these obvious markings of a poor neighborhood, the underlying social distance becomes more obvious.” In addition, now that electricity, water, and decent housing are available to the residents, they must pay an electric bill and a real estate tax. As more costs accrue to the residents from these improvements, the “market mechanism could push poorer people out,” who will no doubt move somewhere, Penglase noted, and start another favela.

Caio Ferraz, a former visiting scholar at MIT, grew up on a favela in Rio. He, his parents, and twelve siblings lived in one room. There was no running water, no electricity, and the bathroom was outside. His father was a construction worker, who later succumbed to alcoholism. His mother, a devout Catholic, worked in the national airport as a domestic. “I know what it means when you have hunger and you don’t have anything to eat,” Ferraz said. “When you have the police go inside of your house and break everything because they don’t respect the law.” Many of his friends have died in the drug wars that plague favelas. “The government doesn’t understand. The only way to change this social situation is to make a big, big investment in education, in health care.”

While tremendous efforts must continue in these neighborhoods, Harvard is pleased to honor J¡uregui and his team for the impressive structural changes they have implemented to bring about social change. “This diligent and ethical professional team models a progressive, more holistic approach to urban design, one that recognizes the value of social research and re-investment in neighborhoods, rather than the outmoded practice of demolition and displacement,” Machado said. “They have used urban design as a tool for social reform and they have succeeded.”

Winter/Spring 2001

Susie Seefelt Lesieutre was a publications intern at DRCLAS for the fall semester and is currently working with the center’s publications director. she is enrolled in the certificate for publishing and communications program at Harvard Extension. In 1990 she received a master’s degree in TESL; she has taught ESL in the US and abroad. This article draws on a 1998 report on Latin American Arts at Harvard by Mercedes Trelles.

Related Articles

Guatemala Diary

In a deeply personal way, I feel like I am home again. Of all the places I have visited, Guatemala is the country I love and feel closest to. Certainly the most impressive aspect is the persevering Mayan people, who endured a 30-year civil war…

Exploring New Horizons in Latin American Contemporary Art

When I first traveled to Peru by boat with my family fifty years ago, the country seemed as far away from Argentina as Boston from Buenos Aires. My husband had been sent there by W.R…

Emotion, Nation and Imagination

Five Colombian-born US based artists exhibited their works in a group show entitled Colombians: Between Emotion, Nation and Imagination, sponsored in part by the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies and the Colombian Consulate…