García Márquez and Cinema

Beyond Adaptations

“…my relations with cinema (…) are those of a marriage on bad terms. That is to say, I cannot live with cinema or without cinema, and judging from the quantity of offers I receive from producers, cinema feels the same way about me.”

—Gabriel García Márquez

Gabriel García Márquez’s passion for film has always been constant and multifaceted. He has written film reviews; he has produced an extensive report about filmmaker Miguel Littin, Clandestine in Chile; he has led script workshops; he has adapted other writers’ stories and novellas as well as his own tales for the cinema; and nearly twenty Latin American, Iberian, and European directors have used his pieces to produce works for the big screen. Moreover, he has created a foundation for New Latin American Cinema, and a School of Cinema and Television for the Third World. The relationship between film and García Márquez is, as he himself confesses, a “marriage on bad terms,” but it has nevertheless borne multiple fruits.

During recent years there has been an increase in “cinematographic Gabomania” since the release in 2007 of the Colombian author’s sole Hollywood movie to date: Love in the Time of Cholera, directed by Mike Nichols. The film production company Argos this year begins filming Noticia de un secuestro (“News of a Kidnapping”), and Costa Rican filmmaker Hilda Hidalgo, a graduate of the school founded by the author, is finishing her adaptation of Del amor y otros demonios (Of Love and Other Demons”), which was offered to her by García Márquez himself at the end of one of his workshops, and which has now become the most ambitious film in Central American cinema.

García Márquez’s fondness for the seventh art – sparked by his grandfather Nicolás Márquez, “who had taken him by the hand in Aracataca to see the films of Tom Mix” – finally blossomed through his work as a film critic beginning in February of 1954. The cinema-loving Gabo took advantage of a trip to Europe in 1955 as a reporter for El Espectador to enroll in the renowned Experimental Cinematographic Center in Rome; notwithstanding, he left after only a couple of months, disappointed by the academic focus of the Center.

Still, his passion for film did not wear out so easily: he returned to Barranquilla planning to establish a film school, a project that he wrote up but never realized. In 1961, he traveled to Mexico:

“…with twenty dollars in his pocket, his woman, a son, and an idea fixed in his head: to make cinema.”

Mexican producer Manuel Barbachano Ponce offered him an opportunity to work on his adaptation of El gallo de oro, a text by Juan Rulfo, done in collaboration with Carlos Fuentes. Soon, they the producers began to take an interest in the writer himself, and García Márquez ceded the rights to his story En este pueblo no hay ladrones so that Alberto Isaac and Emilio García Riera could produce it for the big screen.

In 1964, García Márquez wrote his first original script, Tiempo de morir; an old idea which in that era he called “El charro”. The script was written expressly for Arturo Ripstein, and the dialogues were adapted by Carlos Fuentes. The work marked the beginning of the career of the now renowned Mexican director, Ripstein. Later on, between 1983 and 1985, Colombian director Jorge Alí Triana produced two versions of the same script, one for film and the other for television, and Rodrigo García, son of the Nobel Prize winner, also produced a version of the same script.

García Márquez continued to contribute to the works of Ripstein and of Luis Alcoriza, such as Presagio (1974), considered by some critics to be the best film from this early stage.

While making Presagio, the García Márquez realized that he was writing something very similar to what he wanted to express in a literary form. He shut himself away for eighteen months and emerged with Cien años de soledad (“One Hundred Years of Solitude”) (1967).

The publication and success of this book, which turned him into a world-famous writer, changed the trajectory of his career. From then on, directors would come looking for him to adapt his novellas and stories: María de mi corazón (1979), Eréndira(1982), by Ruy Guerra, La viuda de Montiel (1979), by the Chilean Miguel Littin, El mar del tiempo perdido (1981), by Solveig Hoogesteijn, Un señor muy viejo con unas alas enormes (1988), by Fernando Birri, and Oedipo alcalde (1996), Jorge Alí Triana’s contemporary adaptation of Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex. In 1997, the Italian Francesco Rosi adapted Crónica de una muerte anunciada (“Chronicle of a Death Foretold”) and in 1998, Ripstein filmed El coronel no tiene quien le escriba (“No One Writes to the Colonel”). Additionally, numerous television series and short films have been produced by students of the Script Workshop with the collaboration of the Master.

Nevertheless, we believe that García Márquez’s fundamental contribution to film was the founding of Cuba’s International School of Cinema and Television (EICTV), which has allowed more than 800 youths to learn about the film trade – youths who, without his figure, would have never pursued their interests in film. Gabo is the great father of all young Latin American filmmakers, many of whom have already won international awards. Like Hilda Hidalgo, they are adapting the work of the “father,” but adding a very personal vision of Del amor y otros demonios: a feminine view, a love story, the first film of an EICTV student. A challenge that Hilda accepted with a smile and with the complicity of the master.

García Márquez y el cine (Spanish version)

Más allá de las adaptaciones

Por María Lourdes Cortés

“…mis relaciones con el cine (…) son las de un matrimonio mal avenido. Es decir, no puedo vivir sin el cine ni con el cine, y a juzgar por la cantidad de ofertas que recibo de los productores, también al cine le ocurre lo mismo conmigo.”

—Gabriel García Márquez

La pasión de Gabriel García Márquez por el cine ha sido constante y ha tenido múltiples facetas. Ha escrito crónicas de cine; ha escrito guiones que se han llevado a la pantalla y otros que sólo han visto la luz a través de las palabras; ha escrito un extenso reportaje sobre el cineasta Miguel Littin Clandestino en Chile; ha dado talleres de guión; ha adaptado a la pantalla cuentos y novelas de otros escritores; ha adaptado sus propios cuentos y casi una veintena de directores iberoamericanos y europeos han llevado a la pantalla sus obras o sus guiones.

Pero aún hay más: Gabriel García Márquez ha creado una fundación para el Nuevo Cine Latinoamericano, y una Escuela de Cine y Televisión para el Tercer Mundo. El cine y García Márquez son como él mismo confiesa, un “matrimonio mal avenido”, que, sin embargo, ha dado múltiples frutos.

Durante los últimos años se ha dado un auge de “gabomanía cinematográfica”, ya que se realizó la única película “hollywoodense” del colombiano: Love in times of cholera, de Mike Nichols. La empresa Argos arranca este año el rodaje deNoticia de un secuestro, y la costarricense Hilda Hidalgo, egresada de la escuela fundada por el escritor, está terminando su adaptación de Del amor y otros demonios, que él mismo le ofreció al final de uno de sus talleres, y que se convierte en la película más ambiciosa del cine centroamericano.

La afición de García Márquez por el sétimo arte -que nace del abuelo Nicolás Márquez, “quien lo había llevado de la mano en Aracataca a ver las películas de Tom Mix”- se descubre en la labor de crítico de cine que inició en febrero de 1954. El Gabo cinéfilo aprovechó un viaje como reportero de El Espectador, a Europa, en 1955, para ingresar en el célebre Centro Experimental de Cinematografía de Roma; no obstante, estuvo sólo un par de meses, decepcionado por el academicismo de dicho centro.

Pero su pasión por el cine no se agotó tan fácilmente: volvió a Barranquilla a fundar una escuela de cine, cuyo proyecto redactó, pero que tampoco llegó a realizarse, así que en 1961, viajó a México:

“…con veinte dólares en el bolsillo, la mujer, un hijo y una idea fija en la cabeza: hacer cine.”

El productor mexicano Manuel Barbachano Ponce, le ofreció la oportunidad de trabajar en cine, en la adaptación de El gallo de oro, un texto de Juan Rulfo, la cual realiza en colaboración con Carlos Fuentes. Pronto se empezaron a interesar en el escritor y cedió los derechos de su cuento En este pueblo no hay ladrones para que Alberto Isaac y Emilio García Riera lo llevaran al cine.

En 1964, García Márquez escribe el primer guión completamente suyo, Tiempo de morir; una vieja idea que en aquella época llamó El charro. El guión fue escrito expresamente para Arturo Ripstein y los diálogos fueron adaptados por Carlos Fuentes. Fue el inicio del ya consagrado director mexicano. Posteriormente, entre 1983 y 1985, el director colombiano Jorge Alí Triana realizó dos versiones del mismo guión, para el cine y la televisión, y Rodrigo García, el hijo del Nobel, también anunció una versión del mismo guión.

García Márquez continuó participando en trabajos de Ripstein, de Luis Alcoriza, como Presagio (1974) considerada por algunos críticos como la mejor película de esta primera etapa.

Y haciendo Presagio, el autor descubrió que estaba escribiendo algo muy parecido a lo que quería expresar literariamente. Se encerró dieciocho meses y salió con Cien años de soledad (1967).

Este hecho, que lo convirtió en un escritor de fama mundial, cambió su camino y, en adelante, fueron los directores quienes lo buscaron para adaptar sus novelas y cuentos. María de mi corazón (1979), Erendira (1982), de Ruy Guerra, La viuda de Montiel (1979), del chileno Miguel Littin, El mar del tiempo perdido (1981), de Solveig Hoogesteijn, Un señor muy viejo con unas alas enormes (1988), de Fernando Birri, Edipo alcalde (1996), de Jorge Alí Triana es una adaptación contemporánea de Edipo Rey, de Sofocles. Un años después, el italiano Francesco Rosi adapta Crónica de una muerte anunciada y en 1998, Ripstein rueda El coronel no tiene quien le escriba.

También se han producidos series de televisión y medio metrajes realizados por los estudiantes del Taller de Guión con la colaboración del Maestro.

Sin embargo, consideramos que el aporte fundamental de García Márquez al cine fue la fundación de la Escuela Internacional de Cine y Televisión, de Cuba, que ha permitido a más de 800 jóvenes aprender el oficio del cine y que, sin su figura, nunca hubiera surgido. Gabo es el gran padre de los jóvenes realizadores latinoamericanos, muchos de los cuales ya han ganado premios internacionales o que, como Hilda Hidalgo, está adaptando la obra del “padre”, pero una versión personalísima de Del amor y otros demonios: una mirada femenina, una historia de amor, la primera película de una estudiante de la EICTV. Un reto que Hilda aceptó con una sonrisa y con la complicidad del maestro.

Fall 2009, Volume VIII, Number 3

María Lourdes Cortés is the director of the Fondo de fomento al audiovisual de Centroamérica y el Caribe, the Foundation for Central American and Caribbean Audiovisual Promotion. A professor at the Universidad de Costa Rica and a researcher for the Fundación del Nuevo Cine Latinoamericano, she is author of Amor y traición: cine y literatura en América Latina (1999) and La pantalla rota: Cien años de cine en Centroamérica (2005). She is currently working on a book about García Márquez and film.

María Lourdes Cortés es directora del Fondo de fomento al audiovisual de Centroamérica y el Caribe, la Fundación para la Promoción Audiovisual de Centroamérica y el Caribe. Profesora de la Universidad de Costa Rica e investigadora de la Fundación del Nuevo Cine Latinoamericano, es autora de Amor y traición: cine y literatura en América Latina (1999) y La pantalla rota: Cien años de cine en Centroamérica (2005). Actualmente está trabajando en un libro sobre García Márquez y el cine.

Related Articles

Coconut Milk in Coca Cola Bottles

Common knowledge has it that virtually any movie, once removed from its original cultural context of production and reception, might be either misunderstood and misperceived or re-interpreted and re-signified. Likewise, we may agree that national cinemas seek to define, challenge….

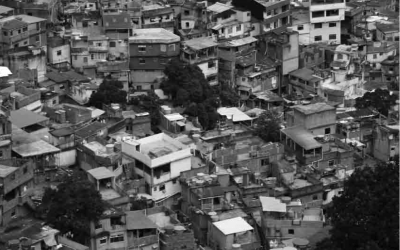

Neither the Sertão or the Favela

To frame the poetics of the ordinary in terms of subtlety and delicateness is to propose an antidote both for cynicism and for what I call Neo-Naturalism. Its appearance, at least in Brazilian cinema and literature, has been clearly identified, ranging from peripheral subjects…

Brazilian Cinema Now

Snow falling in the city of São Paulo, in southern Brazil? Taking a helicopter in São Paulo then arriving a few moments later in the deep wilderness of the Amazon jungle, half a continent further away to the north? Then meeting a white Asian tiger in the heart of the Amazon forest?…