Golden-Epoch Cinema in Mexico

Creating National Myths on the Silver Screen

The acting was appalling, the inconsistencies of plot and character so constant that any occasional consistency seemed glaring. The soft-bodied chorus girls always skipped and wiggled in non-unison and the heroines always sobbed in precisely the same cadence, and no director ever attached negative value to the term “over the top.” During its three-score-long heyday, the Mexican movie industry produced hundreds of movies that scored low in at least one of the categories of wit, good taste, pacing, psychological insight, or complexity—or, sometimes, all of the above.

And yet, as much as any single other force, Mexican movies defined a nation, and an era, in a way that mattered deeply not only to Mexicans: throughout Latin America, the weepy musicals and glamorous dramas held tens of millions of viewers captive in their silvery light. Not for nothing does one of the revolutionary poet Roque Dalton’s best-known poems end with the words: “Let’s see if you sleep as good as you snore/ as Pedro Infante used to say.” [my translation] To this day, Mexicans traveling through points south will generate friendly surprise when their accent is revealed. “Mexicana!” a Peruvian shopkeeper, or an Argentine bureaucrat, will exclaim. And life for the wayfarer will suddenly become easier, as if by virtue of nationality the traveler were somehow to be thanked for the gift of those old-time Mexican movies.

In this country almost no one who is not Latino has ever seen a Mexican movie from the Época de Oro, or Golden Era–as the period from, let’s say, 1938 to 1954 is generally known. And yet, whenever in the course of a lecture I’ve shown a snippet of one of those pinnacles of obsessive sentimentalism, I’ve seen the entire audience relax, visibly let go, at the first strains of a mariachi song, or laugh at the movie’s silliest jokes with good-natured delight, or stare in wonder at the extreme beauty of María Félix. What is it about these bad films that makes them so powerful? Let us say, for the moment, that it is the strength of their conviction in their own Mexicanness.

In the early 1930s, Mexico began to emerge from long decades of revolution and social upheaval into the normality of a daily life, albeit a life transformed not only by the Revolution itself but by an accelerated presence of the modern world. The working class was working, an emerging bureaucracy was giving rise to a new sort of middle class, and at long last it was possible for families to live a predictable life, one in which weekend family entertainment had pride of place. In the burgeoning economy brand-new movie houses, each more glamorous and extravagant than the next, showed hypnotic entertainments. The glimmering figures on the screen could be from anywhere—swashbuckling stars like Douglas Fairbanks and John Barrymore played as important a role in the fantasy life of young Mexican matinee-movie-goers as they did north of the border—but in post-revolutionary Mexico the proud new workers and employees (oficinistas) also wanted their own faces, language, and taste for high drama and great singing up on the screen. Moreover, a country that had seen itself ripped up and turned inside out by nearly twenty years of warfare had a lot of stories to tell, and the factions that emerged victorious from the bloodshed wanted certain stories told their way. Thus, the emergence of a national and nationalistic film enterprise, financed by the government of President Lázaro Cárdenas and, to a lesser degree, by producers in the United States. In the new mythology known asnacionalismo revolucionario, Mexico was not a tangle of corruption, backstabbing factions, religious warfare and outrageous inequality. Instead, it was a nation forged in the fires of revolution, tempered by want, rooted in tradition but emerging triumphant into the modern world. In any other country, perhaps, and certainly at any other point in Mexico’s development, the subjugation of creative endeavor to official history would have reeked of cynicism or propaganda. And propaganda there was, certainly, by the reel, along with ghastly exploitation of the audience’s hunger for “schmaltz,” but the Época de Oro of Mexican cinema coincided with a rare moment, perhaps akin to the first decade of the Cuban or Chinese Revolution, in which a poor and often victimized country believed in itself and thus created itself in the image it was in the act of conjuring. The energy released by this sort of magical thinking can fuel the unlikeliest representations of story.

Take Jorge Negrete, the opera-trained singer from a respectable Northern family, who would embody ranchero culture by erasing the whole notion of social class. Yes, it was true that most rancheros were more dark-skinned—and rather less well-nourished—than he, and that he sang not necessarily traditional ranchero songs wearing a mariachi costume no mariachi had ever worn before (indeed, the whole concept of the mariachi was pretty much a Mexiwood invention). But it was also true that Negrete embodied the Mexican persona at its best: the big-hearted and exquisitely courteous male from la provincia who bears himself with virile elegance and an easy-going smile. Mexicans could both identify with him and ache to be like him. Or take Dolores del Río and Pedro Armendáriz, stars and muses of the artiest of all the Mexican film directors, Emilio (“el Indio”) Fernández. Del Río came from an haute bourgeois family and was a star in Hollywood long before she ever acted in a Mexican movie. Armendáriz inherited his famous green eyes from his American mother, was partly brought up in the United States, and was an unreconstructed bohemian sometime-journalist, sometime art-student, before he turned to acting as a lark. On the face of it, the notion was ludicrous that these two worldly people could embody, over and over again, indigenous Mexican couples crushed by poverty and discrimination. But like Jorge Negrete, Pedro Infante, and a dozen other screen idols, these actors believed so strongly in the archetypes they were helping to create that they came to embody them for the generations. (I am using the overworked term “screen idols” advisedly: Infante’s and Negrete’s funerals, for example, provoked outpourings of national mourning that ended in riots at the cemetery and several reported suicides.) National identity became actors’ and scriptwriters’ substitute for individual personality and character. Or, rather, national identity became character. It is the innocence and conviction with which these representations of identity were enacted onscreen that made them vital, irresistible, and, in some unaccountable way, true.

The last great box office hits of the Época de Oro included the Pedro Infante trilogy about Pepe el Toro–heart-broken hero of the working poor–and the whole cycle of hip-shivering rumbera movies, which made audiences dance and sob late into the 1940s. Then it was over. In the 1950s only the comic actor Tin Tan would command the kind of devotion that made the stars of the Época de Oro household names, but the plots of even Tin Tan’s best movies unravel long before the ending, and there is a frantic energy in his acting that can be read as trying too hard. He remains an old-style icon, but the formulas he clung to lost their magic even as he did his best to prod them back to life.

Towards the end of the 1950s, Mexican movie studios made the decision to shift to color film. The dispirited flatness of the first movies in color, their unbearable triviality, come as a shock after the great outpouring of narrative that the Época de Oro represented. It was as if the whole country had suddenly run out of stories to tell. Moreover, there were less and less stories in common. Mimicking the beach-blanket songfests Hollywood was churning out, Estudios Churubusco produced teen musicals in which stand-ins for Sandra Dee and Troy Donahue bounced aimlessly around the screen, singing tuneless covers off the U.S. pop charts. These misconceived attempts at cosmopolitanism did find an audience (what else, after all, was there to see?), as did the only slightly more original risqué dramas featuring heavy-breathing actresses in their slips, but the social classes no longer mingled at the movie theatre: the middle class surrendered entirely to imports—mostly from the United States––while an entirely different audience favored the still-kicking ranchero genre. (Indeed, the ranchero movie would eventually morph into the narcoepic, appallingly badly-made drug sags whose existence is barely noted by the middle class, but which have found a huge audience, and are currently produced directly for DVD.)

The dominance at the box office of American movie spectaculars, the widespread influence of television, and the demise ofnacionalismo revolucionario, which had collapsed under the weight of its own broken promises, combined to demolish the Mexican film industry by the 1960s, despite the fact that its revival is regularly announced.

In recent years a dozen or so talented young directors—mostly male, mostly devoted to full-length fiction features—have, in fact, revitalized the art, if not the industry. But these new directors are as determined to prove their ability to tell stories about any part of the world as their artistic forbears were to sing the song of Mexico. The standard-bearers of this new wave, Guillermo del Toro, Alejandro González Iñárritu and Alfonso Cuarón, are internationally recognized, and therefore a great source of pride for their many compatriots. But they are still hugely outsold by Spiderman. And because they do not have a truly national audience, as a general rule they are not definers of a new myth of national identity (Y tu mamá también comes to mind as an exception.) Instead, the new wave of directors are individual artists, making highly personal films. This is probably just as well: after all, the Época de Oro fed us lies on a silver spoon, and now we are grown up. But oh, how delicious those lies were, and oh, how we miss them!

Fall 2009, Volume VIII, Number 3

Alma Guillermoprieto is a Mexican-born journalist and author of several books, including Samba and Dancing with Cuba. A 2004-05 Nieman Fellow and a 2006-07 Fellow at the Radcliff Institute of Advanced Studies at Harvard, she taught a seminar on 20th-century Mexican history and movies as a 2008 Visiting Lecturer in Harvard’s Romance Languages and Literature department.

Related Articles

Coconut Milk in Coca Cola Bottles

Common knowledge has it that virtually any movie, once removed from its original cultural context of production and reception, might be either misunderstood and misperceived or re-interpreted and re-signified. Likewise, we may agree that national cinemas seek to define, challenge….

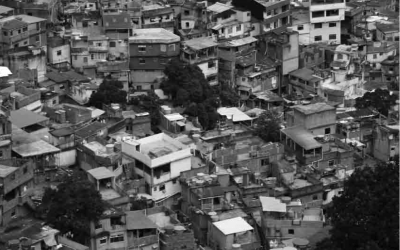

Neither the Sertão or the Favela

To frame the poetics of the ordinary in terms of subtlety and delicateness is to propose an antidote both for cynicism and for what I call Neo-Naturalism. Its appearance, at least in Brazilian cinema and literature, has been clearly identified, ranging from peripheral subjects…

Brazilian Cinema Now

Snow falling in the city of São Paulo, in southern Brazil? Taking a helicopter in São Paulo then arriving a few moments later in the deep wilderness of the Amazon jungle, half a continent further away to the north? Then meeting a white Asian tiger in the heart of the Amazon forest?…