Photoessay: Guatemala, The Aftermath

Repression, Refuge, and Healing

The year 2004 marked the 50th anniversary of the CIA-orchestrated coup in Guatemala that overthrew the democratically elected government of Jacobo Arbenz in the name of U.S. economic interests. CIA piloted planes bombed areas of Guatemala City, and the United States installed a virtual puppet government. Thus began a serried of military dictators and their armies and death squads that would bring incredible suffering and grief to the Guatemalan people over the next four decades and literally up to the present.

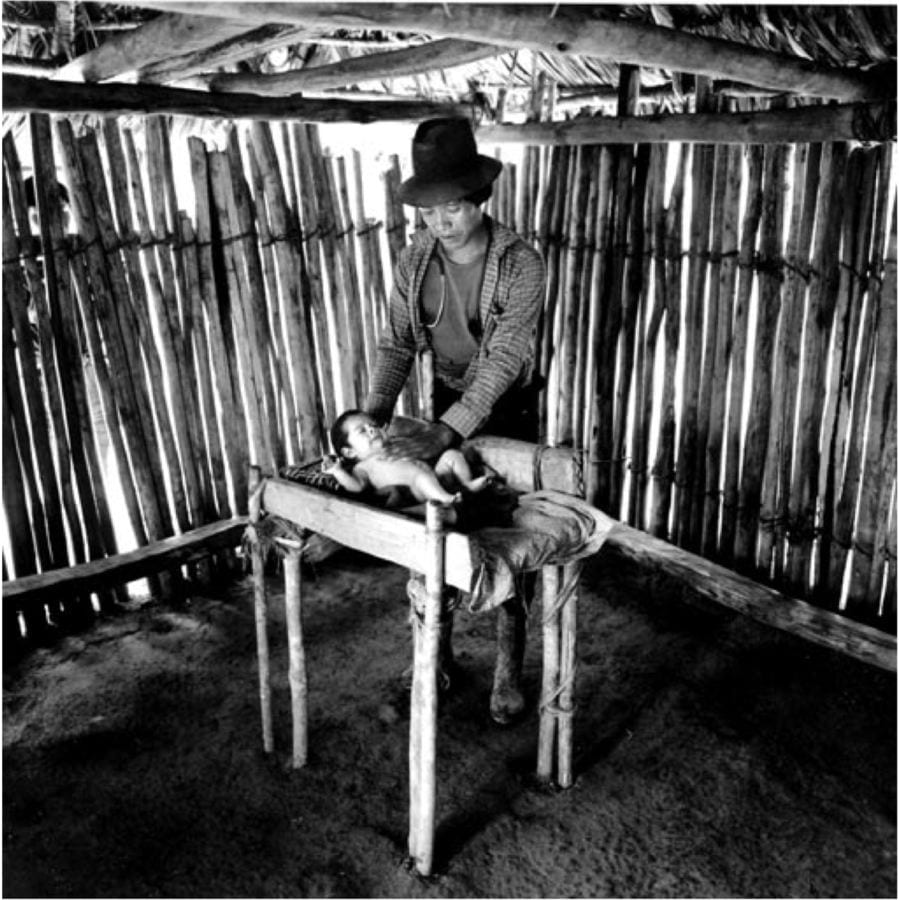

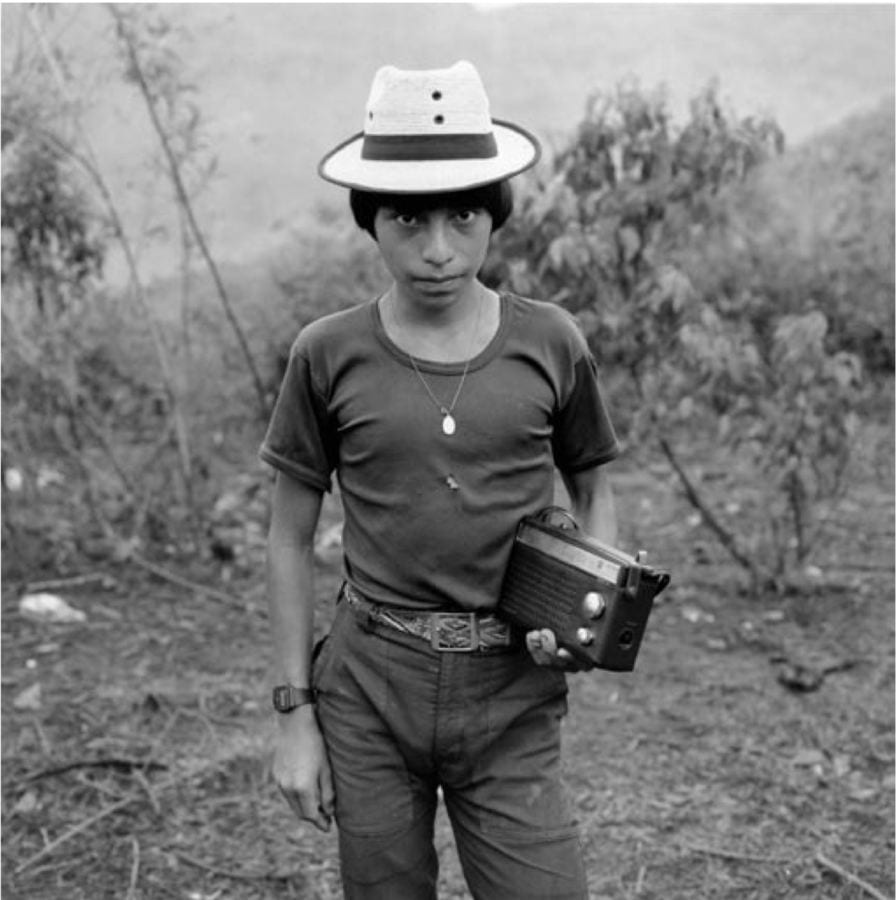

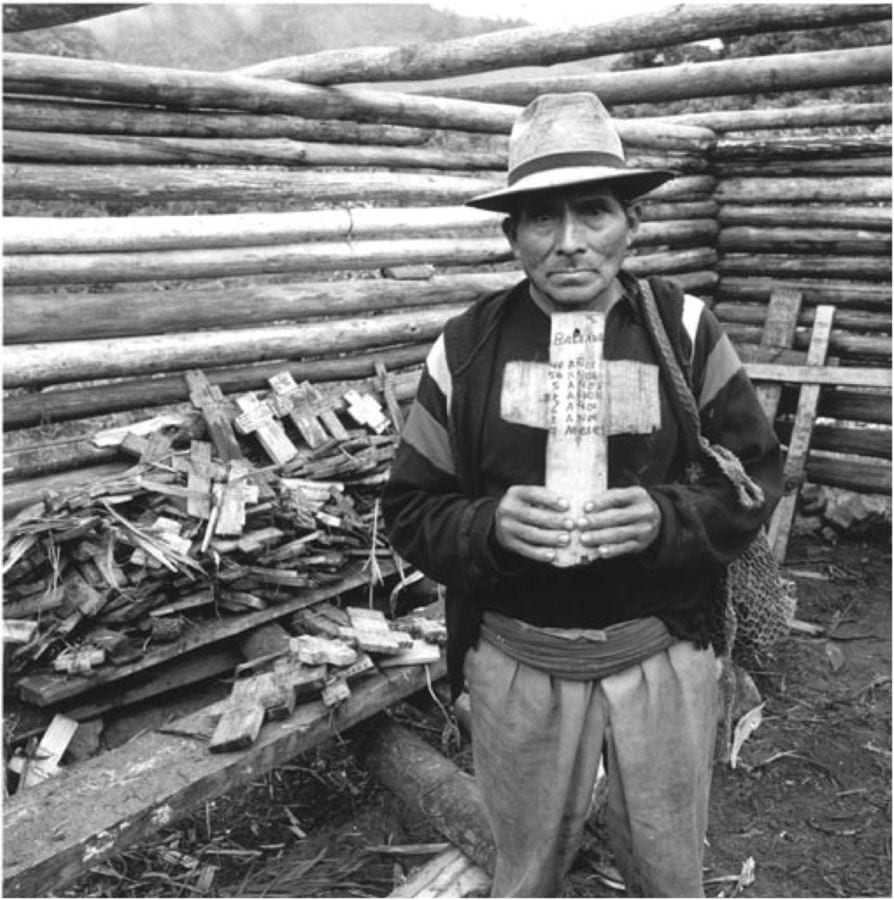

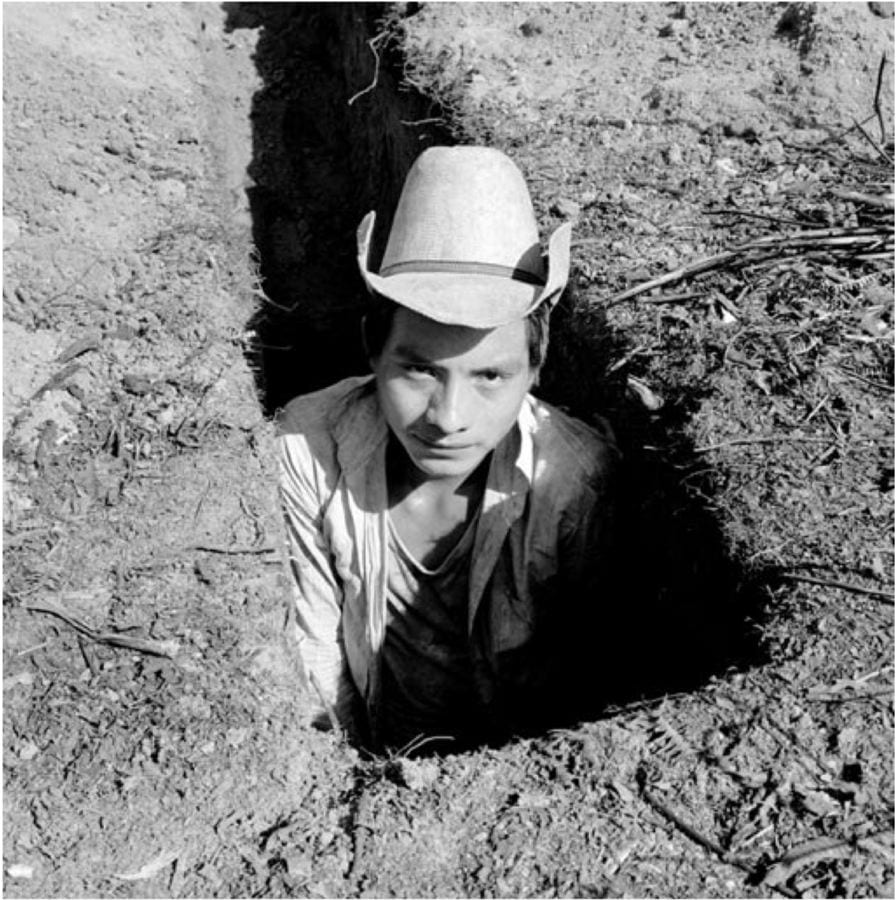

For over six years between 1993 and 2001 I worked as a human rights advocate and freelance photographer in Guatemala, principally working with indigenous Mayans uprooted by that country’s long and brutal civil war. I spent much of my time in rural areas, working to support Guatemala’s displaced and refugee populations in their struggle for respect of their basic rights. Most recently I worked with a forensic anthropology team, supporting and documenting the exhumations of clandestine cemeteries.

When I first arrived in Guatemala from neighboring El Salvador in early 1993, I was only peripherally aware of the extent of the violence and repression that was being carried out with U.S. support against innocent and impoverished populations of that county. In the 1980s, compared to other countries in Latin America—Chile, Argentina, El Salvador and Nicaragua—little news was getting out about Guatemala. U.S. readers often did not hear about the atrocities being carried out there: the massacres, the genocide, the tremendous repression, that were overwhelmingly carried out against the Indigenous, the Mayans, who make up 65% of the total population of that country. In the words of Uruguayan author and journalist, Eduardo Galeano, from his endorsement of my book Our Culture is Our Resistance, “… It was the worst massacre since the times of the Conquest in the 16th century. It happened just twenty years ago, but the world, blinded by racism, never knew.”

The images that appear in this essay are but a few of the hundreds of photographs that I took in the context of my human rights work in Guatemala. The images themselves are stories of life and death, of hope and despair, and of struggles for survival, respect and truth.

My work focuses primarily on the Communities of Population in Resistance (CPRs)— beginning with photographs that I took between 1993 and 1995 in northern Guatemala. The CPRs emerged from the violent repression directed against civilians by the Guatemalan Army in the early 1980ss. While tens of thousands of indigenous campesinos spilled across the border into Mexico, the people who would form the CPRs fled to remote mountain and jungle areas, where they formed highly organized, self-governing communities that silently resisted death and Army control, remaining in hiding until the mid 1990s. During this fifteen-year period, they were accused by the government of being guerrillas, and were hunted by the Army.

Twelve years ago, in those profoundly beautiful mountains and jungles soaked with blood, I joined my passions for photography and social justice. It is my hope that this work not only speaks to my vision as an artist and as an activist, but most especially to the lives of those in Guatemala that survived and resisted death and exploitation, and who continue to struggle for their basic rights, their survival and their dignity. And to those who were killed, but whose memories live on.

For more information about Jonathan Moller’s book, please visit the following websites: <www.powerhousebooks.com/titles/ourcultureisourresistance.html> or <www.jonathanmoller.org>. Spanish language edition by Turner Libros, Madrid & Mexico City: <www.turnerlibros.com>.

Spring/Summer 2005, Volume IV, Number 2

Jonathan Moller worked in Guatemala for six years with the National Coordinating Office on Refugees and Displaced of Guatemala (NCOORD), the Guatemala Accompaniment Project (GAP), and most recently, with the Forensic Team of the Office of Peace and Reconciliation of the Quiché Catholic Diocese. His photographs have been widely exhibited and published. His recent photography book Our Culture is Our Resistance: Repression, Refuge and Healing in Guatemala includes testimonies by survivors of the violence, as well as essays by Francisco Goldman, Susanne Jonas, and Ricardo Falla, among others. Author royalties will be donated to the Association for Justice and Reconciliation in Guatemala.

Related Articles

Introduction: Bush Administration Policy

So it is the policy of the United States to seek and support the growth of democratic movements and institutions in every nation and culture, with the ultimate goal of ending tyranny…

International Symposium in Puebla

It is likely that Don Quijote first reached the Western hemisphere—in what was, at the time, lightning speed—as a stowaway. On September 28, 1605, Franciscan commissioners of the…

Adiós 61 Kirkland

For the past eight years, the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies has made its home at 61 Kirkland Street. Countless film screenings, celebrations and roundtable discussions…