Guatemala’s Police Archives

Breaking the Stony Silence

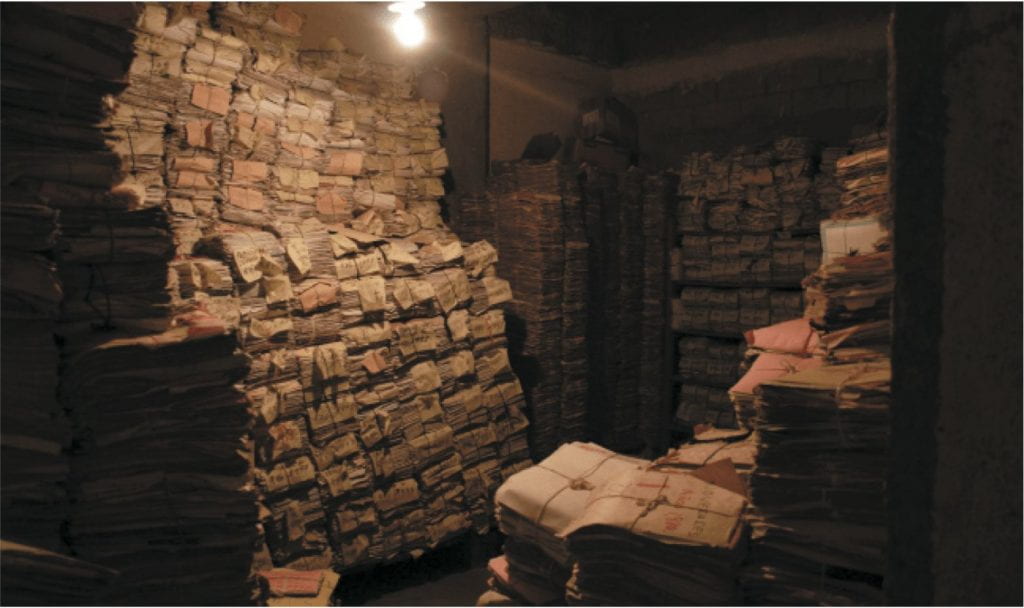

Documents are stacked up at a police station archive in Guatemala City. Photo by Daniel Hernandez-Salazar

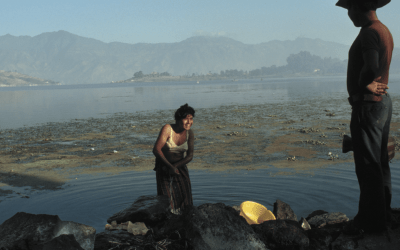

Ana Lucía Cuevas describes living for more than 25 years with the pain of her brother’s disappearance as torture, “as though you are hooded and someone is beating you with a club.” Now the shroud of secrecy is being lifted.

Carlos Cuevas Molina was abducted at gunpoint on May 15, 1984, when he was 24 years old and Lucía was 21. He was a sociology student pursuing a degree at the country’s national University of San Carlos when he and a friend were seized off a street in downtown Guatemala City by a group of armed men and taken away in a car. He was never seen again.

He was one among a quarter of a million victims of the counterinsurgency campaign waged by Guatemalan security forces during and after the cold war. The government forces targeted not only armed guerrilla groups but hundreds of thousands of unarmed civilians in the countryside and urban centers who were considered suspect by association.

After Carlos disappeared, his family filed writs of habeas corpus, demanded meetings with government officials, and gathered what evidence they could. Witnesses described the vehicles used in the operation, including license plate numbers, and linked the abduction to the vicious DIT police unit, the Department of Technical Investigations, known to be behind many of the thousands of abductions that took place in Guatemala City during the early 1980s. But their efforts to investigate ended abruptly in April 1985, when the corpses of Carlos’s young wife, Rosario Godoy de Cuevas, their infant son and her 21-year-old brother were found in the wreck of a car, arranged to look like an accident. Human rights defenders who saw the bodies reported that the child’s fingernails had been torn out.

After those killings, “there was a huge silence,” remembers Lucía. “Everyone was terrorized so there was no way to communicate.” The military government of General Óscar Mejía Víctores denied having information related to either crime. The family fled Guatemala in the face of death threats, settling in Costa Rica.

When Guatemala’s civil conflict ended in 1996, a United Nations-sponsored Commission for Historical Clarification (CEH) was convened to examine the causes of a 36-year war that killed an estimated 200,000 unarmed civilians and disappeared some 40,000 more. Over the course of 18 months, investigators gathered thousands of testimonies from survivors of the conflict, reviewed the data produced by exhumations of secret mass grave sites around the country, analyzed news accounts and dug through human rights reports. What the commission was unable to obtain were records from inside Guatemala’s death machine.

The commission’s final report found government forces responsible for 93 percent of the massacres, abductions, assassinations, cases of systematic torture and other human-rights crimes documented by CEH investigators. But it reached those conclusions without the benefit of the state’s files. Despite a mandate that gave them the right to collect the internal archives of the parties of the conflict, investigators were stonewalled by military and police officials at every turn.

The commission presented its report to the public in a revelatory ceremony held in the cavernous National Theater in downtown Guatemala City on February 25, 1999. As President Álvaro Arzú Irigoyen listened, scowling, from the front row, CEH lead commissioner, Christian Tomuschat—a German jurist accustomed to the wealth of documentation available on his own country’s bloody past through the Nazi files and the records of East Germany’s Stasi intelligence service—stood before the audience of thousands and openly berated the government for preventing the commission from gaining access to Guatemalan archives.

More than ten years later, the stony silence of Guatemala’s secret-keepers is coming to an end. The astonishing, unexpected and wholly accidental discovery of a treasure trove of government records five years ago has demolished the government’s ability to pretend that it does not continue to possess and protect archives of the war. The discovery was made in July of 2005, when a small team of inspectors sent to a sprawling police base by the Guatemalan Human Rights Prosecutor’s Office, in response to concerns about the improper storage of ammunition, stumbled upon the documents in the course of its visit. The archive belonged to the former National Police, an institution intimately linked to some of the worst atrocities committed during the war. The force was abolished by the peace accords and rebuilt as the National Civil Police in 1997.

The inspectors understood the significance of their discovery instantly, and within days the Human Rights Prosecutor obtained a judge’s order granting his office the right to secure the site and examine the documents. The task was daunting.

The police records had been stored in a state of almost total neglect, piled haphazardly on every available inch of space inside several crumbling buildings on the edge of the base, where they became infested with bugs and bats, moldering under the drip of water from broken windows. Yet through years of dedicated work and deliberation, and with the help of funding from half a dozen European governments, a staff of some 150 men and women has slowly restored the mass of damp, filthy paper to something resembling a proper archive. Teetering piles of documents tied together with string have been separated, dried, cleaned, described and scanned into a vast database of 10.7 million images. The records themselves are boxed and stored in a secure site on the base; the images are now available to any researcher who wishes to visit what has become the Historic Archive of the National Police.

Gustavo Meoño Brenner is the archive’s director. He has overseen not only the rescue phase of the project but the current investigative phase, in which teams of staff researchers review the records for evidence of human rights crimes. He is the first to admit that managing an operation of this magnitude has called for unusual tactics. “We have had to find creative and audacious solutions in order to be able to respond,” he explained in an interview. Within weeks of entering the site, investigators realized that the files represented the entire archive of the former National Police, dating from the 19th century, when the police force was created, to the institution’s final year. To identify the most important human rights information among the estimated 8 linear kilometers of paper, photographs, audio tapes and computer files, the staff has focused its efforts on the documents produced during the most violent period of Guatemala’s conflict, from 1975 to 1985.

One of the creative solutions employed has been to invite researchers to review files pertinent to their work. These “external investigators,” as Gustavo calls them, can also flag documents relevant to other human rights cases. That way each researcher brings added value to the broader project of hunting down human rights evidence. Another practice has been to let external investigators come outside normal working hours. That lets family members with day jobs search for information about their loved ones.

Above all, it is the policy of total public access that the archive has created that represents the project’s most startling innovation. Gustavo considers it “one of the most important advances that we have made.” The policy was crafted in July 2009, just after the government of President Álvaro Colom took the protective step of transferring formal control of the police archive from the Ministry of the Interior to the Ministry of Culture. The move dispelled a lingering fear among the staff about the independence of their project and freed it to reach out to the public more fully than had before. In July, the archive’s new “Access to Information Unit” opened its doors to the public. Since then, according to statistics compiled by staff, the archive has received 3,447 requests for information, to which they have responded with 55,628 document pages.

For Guatemala, any access to government information about the civil conflict is extraordinary. The archive went a step further. After examining models of public use proposed by similar “archives of repression” in Latin America—in Paraguay, Mexico and Argentina, for example—the Guatemalans chose to place no restrictions on the access enjoyed by outside researchers. That means that not only family members but journalists, students, prosecutors, historians and human rights investigators, Guatemalan or foreign-born, can request records related to any individual, organization or incident and expect an uncensored response. Gustavo calculates the estimated returns on requests so far to be 80% positive, with 20% of requests resulting in no documents. The contrast to other, similar archives in the region is striking; in Argentina’s Comisión por la Memoria, for example, a collection of important records from the La Plata secret police, the names and other pertinent information about victims of the dirty war are withheld from everyone but family members, leaving most researchers in the dark about the social impact of repression.

The investigations under way inside the police archive coincide with a new interest on the part of the government. The Public Ministry is now actively pursuing evidence for a set of human rights cases. Although the Guatemalan authorities have long resisted prosecuting past human rights crimes, a convergence of internal and external pressures has finally set the wheels of justice turning.

President Colom—nephew of a popular politician, Manuel Colom Argueta, who was assassinated by the Romeo Lucas García regime in 1979—has called for the opening of the army’s archives about the civil conflict. That modest exhibition of political will has invigorated human rights organizations to demand a response from the military. The Public Ministry also has been prodded into action by international actors, led by the Dutch Embassy and the U.S. Agency for International Development, which have provided funding for judicial investigations into some of the most pressing human rights cases from the past. Cases now under investigation include the horrific massacre of more than 250 residents of the tiny settlement of Dos Erres in the northern department of the Petén in 1982; the disappearance of a well-known labor leader, Edgar Fernando García, from a street corner in Guatemala City in 1984; a series of dozens of kidnappings and executions of suspected militants and their family members during 1983-85, chronicled in a leaked army intelligence document known as the “Military Logbook” (Diario Militar); and the torture and murder of Efraín Bámaca, guerrilla leader and common-law husband of U.S. citizen Jennifer Harbury.

A United Nations-supported team of international investigators has added to the pressure for justice in Guatemala since January 2008. Their job is to ferret out corruption and expose organized crime. Under the leadership of Spanish jurist Carlos Castresana, the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala, or CICIG, was designed to work with Guatemalan police, prosecutors and judges to assemble some of the most sensitive criminal cases, often targeting the country’s most powerful and well-connected figures. CICIG has gone after members of the police and army, former defense ministers and one former president on charges ranging from embezzlement to drug trafficking to running death squads.

Last May, the commission’s successes appeared briefly to imperil its own survival, when a newly appointed Attorney General, Conrado Reyes, began firing prosecutors involved in the corruption investigations, threatening to undo the hard work that CICIG and the Public Ministry had achieved over two years. Castresana retaliated by abruptly announcing his resignation during an explosive press conference in which he revealed evidence linking Reyes to organized crime, and in a second press conference days later by exposing a nasty smear campaign directed against him. Within a week of Castresana’s resignation, Guatemala’s Supreme Court had removed Reyes and ordered a new selection process to begin for his post. The United Nations named Francisco Dall’Anese, a former Costa Rican Attorney General with experience in government corruption cases, to take over CICIG in late June.

Guatemala’s incipient fight against impunity has weathered the crisis for now. The Public Ministry has rehired many of the attorneys dismissed by Reyes and their joint investigations with CICIG into corruption and organized crime continue. Work has also resumed in earnest on the human rights cases from the past, including efforts by prosecutors to locate hard evidence of state violence among the millions of pages of the police archives. In March 2009, prosecutors used records from the archive to indict four former police officers for their role in the 1984 forced disappearance of labor leader Fernando García. The case was presented to an investigating judge in July of this year—the first one to head for trial in which the government’s own historical archives will be part of the evidence used to charge human rights violators. Today Public Ministry requests for documents represent almost a third of all inquiries submitted to the archive’s Access to Information Unit.

When the police archive opened in 2009, Lucía Cuevas was among the first family members to arrive seeking information about their loved ones. She hoped to find something, anything, which would help her understand how her brother disappeared. What she received was beyond her wildest expectations. In addition to surveillance and operational reports relevant to Carlos’s case, archive staff found a list of license plate numbers assigned to undercover police cars.

Among them was the license number reported by an eyewitness to Carlos’s kidnapping filed more than 25 years ago. The effect on Lucía’s life has been dramatic.

“We always knew who was behind what was happening to us,” she says now. But when the documents arrived, “it was as though the hood had been suddenly lifted.” She has ended her long silence and is completing a long documentary about her brother’s abduction, named after a poem that her mother wrote shortly after he dissappeared: “To Echo the Pain of Many.” Lucía feels now that her life has been transformed. “Until two or three years ago I had lost my identity,” she explains. With the re-opening of the case, “my life has come back to me. My Guatemalan life came back to me. It has been incredible. This is the importance of recovering memory.”

Fall 2010 | Winter 2011, Volume X, Number 1

Kate Doyle is a senior analyst and director of the Guatemala Documentation Project at the National Security Archive, a non-profit library and research institute based at George Washington University. The Guatemala Police Archive will receive a Special Recognition Award at the 34th Annual Letelier-Moffitt Human Rights Awards: http://www.ips-dc.org/about/letelier-moffitt.

Related Articles

Guatemala: Editor’s Letter

The diminutive indigenous woman in her bright embroidered blouse waited proudly for her grandson to receive his engineering degree. His mother, also dressed in a traditional flowery blouse—a huipil, took photos with a top-of-the-line digital camera.

Making of the Modern: An Architectural Photoessay by Peter Giesemann

Making of the Modern An Architectural Photoessay by Peter Giesemann Fall 2010 | Winter 2011, Volume X, Number 1Related Articles

Increasing the Visibility of Guatemalan Immigrants

Guatemalans have been migrating to the United States in large numbers since the late 1970s, but were not highly visible to the U.S. public as Guatemalans. That changed on May 12, 2008, when agents of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) launched the largest single-site workplace raid against undocumented immigrant workers up to that time. As helicopters circled overhead, ICE agents rounded up and arrested …