Herbs, Roots and Magical Remedies

Indigenous Knowledge: Resisting Spousal Violence

The evening of March 25, 1631, a woman named María de Archuleta, of about 30 years of age, was summoned by the Inquisition in Santa Fé, New Mexico. When the commissary asked her if she knew why she had been called, she responded that she presumed they wanted to know about Beatriz de los Ángeles, a Mexican Indian woman, who was said to have enchanted and murdered a man named Diego Vellido.

Three years earlier, Vellido had told Archuleta that he had a special friendship with Doña Beatriz de los Ángeles. After she gave birth to a baby who died, Vellido beat her up. In retribution, de los Ángeles gave him a morsel in a pot of milk that caused him to fall ill. Distressed, Vellido demanded that she help him feel better. She prepared a remedy for him, and although he felt better momentarily, he eventually died. De los Ángeles had a grown daughter named Juana de la Cruz, who—according to Archuleta—also had a lover, Hernando Marquez Sambrano. He was said to have hit de la Cruz out of jealousy and she in turn enchanted him, causing his death.

Archuleta’s testimony came a few days after all the citizens of the region had been ordered to attend a public ceremony at the Church of San Miguel in Santa Fé. During the ceremony, Fray Estebán de Perea was inaugurated as the Official Commissary of the Inquisition for the region of New Mexico, and Fray Andrés Gutierres read an auto de fé, a document listing all the practices that diverged from Catholicism and that were punishable by the Inquisition. The crimes listed included the use of peyote and other medicinal herbs, engagement in witchcraft and sorcery, practicing Judaism, Lutheranism and other European religions, ownership of prohibited books, blasphemy and bigamy. Anyone guilty of these transgressions should confess before the tribunal, and anyone who knew of anyone else who was guilty should denounce what they knew.

I learned about these events when I was researching the involvement of women in healing practices in New Spain during the 17th century. I was interested in exploring the participation of Indigenous women in the maintenance of the physical and emotional wellbeing of New Spanish society during the colonial period. I also wanted to know whether Indigenous beliefs challenged the establishment of Catholicism, and to what extent they shaped the religious imagination of colonial settlers in this context.

As I was searching for historical evidence, I came across a body of documents from a tribunal of the Inquisition in New Mexico dated between 1626 and 1632. This was my first encounter with 17th Century Spanish paleography—the type of script used back in the 1630’s—, but with the assistance of a historic dictionary, I was able to decipher the text within a few days.

The frequency with which accounts of heartbreak, betrayal, and acts of physical violence committed against women appeared in the Inquisitorial record was notable, but more outstanding was the level of impunity enjoyed by the men who harmed women. The story of how Diego Vellido battered Beatriz de los Ángeles was told as as tangential detail to a broader narrative that demonized Beatriz for seeking to avenge him.

When speaking of their own experiences, witnesses used explicit words such as aporriar, reñir, malratar, ( “to hit,” “to fight,” “to mistreat”) to describe the events that led them or those they were accusing to seek revenge against their spouses. In other cases, witnesses spoke of fear of abandonment. In short, all throughout the Inquisitorial record, legal documents from divorce trials and documentation of marital disputes revealed how many women accused their husbands of giving them la mala vida, “a ‘bad life.”

Accounts of infidelity and abandonment, of consistent failure to provide financial support for their wives and children, and of physical and sexual violence reveal a painful and complex panorama for women in the colonial world. Devoid of institutional avenues to defend themselves, colonial women settlers counted on Indigenous women and their knowledge about the natural world to procure different magical remedies, which they hoped would help them solve their marital problems.

Such was the case of Petronilla de Zamora, a 33-year-old woman who appeared before the Inquisition the same day as María de Archuleta. Petronilla de Zamora told the Inquisitors that since her parents married her off at the tender age of eleven and her husband mistreated her, she had to seek advice from one of her servants, an Indian woman, who gave her an herb and told her to chew it and spread it over the doors through which her husband entered. In doing so, her husband would stop mistreating her and would love her well. Zamora put this advice into practice but since it was not fruitful, she threw the herb away. In contrast to Archuleta, who was summoned by the Inquisition, Zamora appeared voluntarily and claimed that she was there to ease her guilty consience as she had just come to the realization that she had committed a grave transgression against the Church.

María de Archuleta and Petronilla de Zamora were two of the nine individuals who appeared before the tribunal less than a week after the Inquisition was officially established in New Mexico. They confessed having used roots, herbs and remedies for different purposes, and denounced those of their neighbors who had done the same. All of them accused Beatriz de los Ángeles and her daughter Juana de la Cruz of murdering their lovers and of engaging in practices that fell under the category of witchcraft and superstition. The number of witnesses who recounted these types of stories increased over the course of the following months. By November 1631, a total of fifty people had testified before the tribunal. Some of them were summoned while others appeared voluntarily.

The Inquisition aimed to ensure the proper practice of Catholicism by policing the intellectual, social, sexual and spiritual worlds of Europeans, criollos, mestizos, mulattos, and Africans. The tribunal of the Holy Office was officially established in New Spain in January 1569 after King Phillip II issued a mandate in Spain. A year and a half later, in August 1570, the King removed Indigenous individuals from the jurisdiction of the Holy Office, which by that time oversaw the spiritual matters of all of New Spain, including the territories of modern-day Philippines, Guatemala and Nicaragua.

Indians from different communities continued to be persecuted and coerced into converting to Christianity by different religious and political bodies, but after 1571 the Inquisition did not persecute or punish Indigenous individuals for their heterodoxy. Yet, in their efforts to maintain a Catholic religious order, Inquisitors tracked down Indigenous beliefs and practices that breached daily life, and punished Europeans, criollos, mestizos, mulattos and Africans who engaged with them.

The documents I worked with in this investigation do not provide sufficient evidence to unearth the stories of Indigenous women who lived in colonial New Mexico, but they provide some insight into how the Indigenous worldview permeated the worldview of Catholic Europeans, criollos, mestizos, mulattos and Africans. These documents also suggest that women from multiple racial backgrounds and social classes formed networks of solidarity that were sustained by the transmission of Indigenous knowledge. The declaration of Juana Sánchez, a 35-year-old mulatta who testified on June 22, 1631, exemplifies what these networks were about.

The Inquisition summoned Sánchez one Sunday morning, a day after other women— including her own sister—had denounced her. During the interrogation, they asked her whether she knew anything about anyone using herbs or roots to recover the affection of their spouses. Sánchez responded that a few years ago she reached out to a Tewa woman from the village of San Juan and asked her for an herb to make her husband stop mistreating her. Sánchez’ husband was being unfaithful and had battered her on repeated occasions, so she wanted to retaliate.

The Tewa woman gave Sánchez a yellow root and two grains of corn and told her to grind the root and rub the paste onto her husband’s chest. This way her husband would stop being unfaithful and his heart would return to him. Sánchez did so. Then she gave the same advice to her sister and to another woman named Beatriz de Pedraza whose husbands were mistreating them. Beatriz de Pedraza was Spanish or criolla, and Juana’s sister was mulatta. Both women had testified the day before, and the Sánchez testimony corroborated what they had told the Inquisitors.

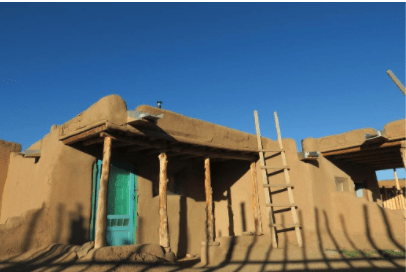

The Tewa woman who provided Sánchez with this remedy was probably a descendant of Tanos (Tewa) Indians, one of the many groups who had lived in and around the area for thousands of years. Up to the Spanish conquest, the area was called Kua’ p’o-oge or O’gha Po’oge, “The Place of Shell-beads Near the Water,” or “Bead Water Place,” in two Tewa dialects from Ohikay Owingeh and Santa Clara.

When the Spaniards arrived, there were about 60,000 to 80,000 inhabitants in approximately 100 communities scattered along the Rio Grande, and to the west beyond the border with present day Arizona. Each group was predominantly autonomous and multiple languages were spoken in the area. To the Spanish settlers, the adobe-styled multi-storied dwelling places where the locals lived looked like Spanish pueblos (“towns”), so they decided to call the local peoples of the area Pueblo Indians.

By 1631, the area’s racial and cultural landscape had shifted. The number of independent Indigenous communities had been significantly reduced due to illness and colonization. People from multiple racial backgrounds intermarried, producing children who did not fit into previous racial categories thereby complicating racial hierarchies. And when Europeans, criollos, mestizos, mulattos and Africans migrated to New Mexico from other parts of New Spain, Mexican Indians from different backgrounds, such as Beatriz de los Ángeles and her daughter Juana de la Cruz came along bringing with them practices and beliefs from their own communities. In fact, several of the people that Estebán de Perea interrogated during his investigation confessed that they used remedies made of peyote, a mind-altering cactus that had been sacred to Mexican Indians for hundreds of years.

The idea that the remedy that Sánchez used on her husband would make his heart return resonates with a specific aspect of the pre-Hispanic worldview of Pueblo Indians. American historian Ramón Gutierrez has argued that in pre-Hispanic times, a common belief among the inhabitants of the Rio Grande area was that the well-being of their communities depended on the physical and psychological health of their members. The strength of human beings was believed to reside in their hearts, so sorcerers caused people to fall ill by shooting objects into their bodies and draining their hearts out. Healers helped those who were ill to gain back their hearts by sucking out the objects shot into them by the sorcerer. (When Jesus Came the Corn Mothers Went Away, 1991.) By the time Juana Sánchez testified before the Inquisition, pre-Hispanic beliefs about illness and well-being had been shaped in a myriad of ways, but her declaration proves that certain themes from spiritual world of local peoples colored the imagination of those who settled in colonial New Mexico.

Colonial New Mexico was a world full of contradictions. Christians engaged in non-Catholic practices but also attended mass on a regular basis. They seemed to fear the wrath of God but also experimented with herbs and roots that they believed were magical. Violence against women was common, but so were instances of retaliation. Women created alliances and helped each other, but they also denounced their relatives and neighbors before the authorities. This was a complex society where individuals were full of emotion and passion. Many of the women represented in this body of documents went beyond the servile conformity that was expected of them by daring to engage with forms of knowledge that were foreign to them. In doing so, they seem to have gained a sense of agency and control over their situation even if momentarily.

While it is impossible to prove the veracity of the events accounted for in these declarations, the Inquisitorial record suggests that Indigenous beliefs and practices permeated multiple aspects of daily life in colonial New Mexico offering an avenue for non-Indigenous women to retaliate against spousal violence. And while settlers disrupted the world of local peoples with their arrival, the process of transformation was not unidirectional. In their attempts to control the people and the land, their intellectual and imaginative worlds were also vastly transformed.

Hierbas, raíces y pócima mágicas

La sabiduría Indígena: resistencia en contra de la violencia marital

Por Juliana Ossa Cohen

En la noche de Marzo 25 de 1631, una mujer llamada María de Archuleta, de aproximadamente 30 años, fue convocada por el tribunal de la Inquisición en Santa Fe, Nuevo Méjico. Cuando el comisario le preguntó si conocía la razón por la que había sido convocada, ella respondió que presumía que ellos querían saber más sobre Beatriz de los Ángeles, una Indígena mejicana, de quien se decía había hechizado y asesinado a un tal Diego Vellido. Tres años atrás, Vellido le había contado a Archuleta sobre la relación de amistad especial que sostenía con Doña Beatriz de los Ángeles. Después de que esta dio a luz a una criatura que falleció, él la golpeó. En respuesta a esa paliza, Doña Beatriz le dio un bebedizo con leche que enfermó a Vellido. Este, afligido, le pidió ayuda a Beatriz para sentirse mejor. Ella le preparó otro bebedizo que, aunque lo alivió momentáneamente, eventualmente le causó la muerte.

Beatriz tenía una hija, Juana de la Cruz quien, según Archuleta, también tenía un amante llamado Hernando Márquez Sambrano. Se decía que Sambrano, presa de celos, golpeaba a Juana. Ella, en respuesta, lo hechizó causándole la muerte.

El testimonio de Archuleta llegó pocos días después de que se les había ordenado a los vecinos de la región asistir a una ceremonia pública en la Iglesia de San Miguel en Santa Fe. Durante la ceremonia Fray Esteban de Perea de inauguró como Comisario Oficial de la Inquisición para la región de Nuevo Méjico y Fray Andrés Gutierres dio lectura a un auto de fe, un documento que contenía un listado de todas aquellas prácticas que se desviaban del Catolicismo por lo que eran objeto de castigo por parte de la Inquisición. La lista de crimenes incluía el uso del peyote y otras hierbas medicinales, actos de brujería y hechicería, la práctica del Judaísmo, Luteranismo u otras religiones europeas, la posesión de libros prohibidos, la blasfemia y la bigamia entre otras. Cualquier persona que se encontrara culpable de estas transgresiones debía confesarlo ante el tribunal y aquel que tuviera conocimiento de algún culpable, estaba obligado a denunciarlo.

Tuve conocimiento de estos hechos durante mi investigación sobre la participación de las mujeres en prácticas curativas en la Nueva España del siglo 17. Estaba interesada en explorar el nivel de contribución de las mujeres Indígenas en el bienestar físico y emocional de la sociedad de la Nueva España durante la Colonia. También quería saber si las creencias Indígenas desafiaban el establecimiento del Catolicismo y hasta qué punto permearon el imaginario religioso de los colonizadores, dentro de este contexto.

En mi búsqueda por evidencia histórica encontré un conjunto de documentos de un tribunal de la Inquisición de Nuevo Méjico, correspondientes al periodo entre 1626 y 1632. Esta fue la primera vez que me enfrentaba a la paleografía española del siglo 17 – el tipo de escritura que se utilizaba en esa época-, pero con la ayuda de un diccionario histórico pude descifrar el texto en pocos días.

La frecuencia con la que aparecían en los registros de la Inquisición actos de traición, desamor y violencia fisica cometidos en contra de las mujeres era llamativa, pero más llamativo aún era el nivel de impunidad del que gozaban aquellos hombres que maltrataban a las mujeres. La historia de la forma en que Diego Vellido golpeó a Beatriz de los Ángeles fue registrada como un detalle tangencial, dentro de una narrativa más amplia que demonizaba a Beatriz por haber buscado represalia.

Al referirse a sus experiencias personales, los testigos utilizaban palabras explicitas como “aporrear”, “reñir”, “maltratar”, para describir los hechos que las llevaron a ellas mismas o a las acusadas, a vengarse de sus parejas. En otros casos, los testigos hablaban del miedo al abandono.

En resumen, a lo largo de todo el registro de juicios de divorcio o disputas maritales de la Inquisición se evidencian muchos casos de acusaciones de mujeres contra sus maridos, por darles “la mala vida”.

Las innumerables historias de infidelidad y abandono, de incapacidad para proveer apoyo financiero a sus esposas e hijos y de violencia fisica y sexual revelan un panorama doloroso y complejo para las mujeres de la Colonia. Desposeídas de cualquier vía institucional para defenderse, las mujeres colonizadoras contaron con la ayuda de sus congéneres Indígenas y su conocimiento ancestral para obtener una variedad de curas mágicas, con las que esperaban resolver sus problemas conyugales.

Tal fue el caso de Petronilla de Zamora, una mujer de 33 años que apareció ante la Inquisición el mismo día que María de Archuleta. Zamora contó ante los Inquisidores que desde que sus padres la entregaron en matrimonio a la tierna edad de once años, sufrió terribles maltratos por parte de su esposo, obligándola a buscar ayuda de una de sus sirvientes, una mujer Indígena-, quien le ofreció una hierba para que la masticara y la esparciera sobre los dinteles de las puertas por donde ingresaría su esposo. De esta forma él dejaría de maltratarla y la amaría buenamente. Zamora puso en práctica el consejo, pero al darse cuenta de su ineficacia, se deshizo de la hierba. A diferencia de Archuleta quien había sido convocada por la Inquisición, Zamora se presentó voluntariamente expresando su deseo de liberar su conciencia, pues sólo hasta ahora se habúa dado cuenta de haber cometido una trasgresión grave en contra de la Iglesia.

María de Archuleta y Petronilla de Zamora fueron dos de nueve personas que aparecieron ante el tribunal a menos de una semana de que la Inquisición se instalase oficialmente en Nuevo Méjico. Confesaron haber utilizado raíces, hierbas y pócimas con diferentes propósitos y delataron a aquellos vecinos que habían hecho lo mismo. Todos ellos acusaron a Beatriz de los Ángeles y a su hija Juana de la Cruz, de haber asesinado a sus amantes y de estar involucradas en prácticas de hechicería y superstición. El número de testigos que declaró en estos casos aumentó en la medida en que pasaban los meses, y para Noviembre de 1631 habían testificado cincuenta personas ante el tribunal. Algunos testigos fueron convocados, mientras que otros se presentaron voluntariamente.

El propósito de la Inquisición era asegurar la práctica correcta del Catolicismo, vigilando el desarrollo de la vida social, sexual, intelectual y espiritual de los europeos, criollos, mestizos, mulatos y africanos. El tribunal del Santo Oficio se estableció oficialmente en la Nueva España en Enero de 1569, mediante mandato real expedido por el Rey Felipe II en España. Año y medio después, en Agosto de 1570, el Rey retiró a los Indígenas de la jurisdicción del Santo Oficio, el cual supervisaba todos los asuntos espirituales de la Nueva España, incluyendo los territorios hoy conocidos como Filipinas, Guatemala y Nicaragua.

Las diferentes comunidades Indígenas continuaron siendo perseguidas y coaccionadas a convertirse al Cristianismo por otras instituciones políticos y religiosos. Sin embargo, a partir de 1571, la Inquisición dejó de perseguir y castigar a los Indígenas por sus creencias heterodoxas.

No obstante, en su esfuerzo por mantener el orden religioso Católico, los Inquisidores rastreaban aquellas prácticas y creencias Indigenas que no cumplieran con los preceptos del Catolicismo, y castigaban a los europeos, criollos, mestizos, mulatos y africanos que se involucraran con las mismas.

Los documentos con los que trabajé en esta investigación no contienen suficiente evidencia para desenterrar las historias de las mujeres Indigenas que vivieron durante la época de la colonia en Nuevo México, pero permiten apreciar cómo la cosmovisión de los Indígenas permeó la cosmovisión de los católicos europeos, criollos, mestizos, mulatos y africanos. Estos documentos también sugieren mujeres de orígenes raciales y sociales diversos conformaban redes de apoyo y solidaridad, los cuales dependían de la transmisión del conocimiento Indígena. La declaración de Juana Sánchez, mulata de 32 años, quien testificó el 22 de Junio de 1631 lo ejemplifica perfectamente.

La Inquisición convocó a Juana Sánchez una mañana de domingo, un día después de que otras mujeres, incluyendo su propia hermana, la habían denunciado. Durante el interrogatorio le preguntaron a Sanchez si tenía conocimiento sobre la utilización de hierbas y raíces para recuperar el afecto de la pareja. Sanchez respondió que unos años atrás había acudido a una mujer Tewa, del poblado de San Juan para pedirle una hierba que la ayudara a acabar con los malos tratos de su esposo. Este le estaba siendo infiel y la golpeaba con frecuencia, por lo que Juana deseaba tomar represalias.

La Mujer Tewa le entregó una raíz amarilla y dos granos de maíz y le indicó que los moliera y esparciera el ungüento en el pecho de su esposo. De esta forma, el esposo dejaría de serle infiel y su corazón volvería. Juana siguió las instrucciones de la mujer Tewa y además le dio el mismo consejo a su hermana y a otra mujer llamada Beatriz de Pedraza, cuyos esposos también las maltrataban. Beatriz de Pedraza era española o criolla y la hermana de Juana Sanchez era mulata. Ambas mujeres habían declarado el día anterior y el testimonio de Sanchez corroboraba lo dicho por ellas.

La mujer Tewa que le proporcionó el remedio a Juana era probablemente descendiente de los Indios Tanos (Tewa), uno de los grupos locales que habían habitado la zona durante miles de años. Hasta la llegada de los españoles, la zona se conocía como Kua’ p’o-oge o O’gha Po’oge, “Lugar de las Conchas Cerca del Agua” o “Lugar de Conchas de Agua” en dos lenguas diferentes de Ohikay Owingeh y Santa Clara.

Cuando llegaron los españoles, la población de los alrededores del Rio Grande hacia el oeste, mas allá de la frontera con lo que hoy es Arizona, sumaba entre 60.000 y 80.000 habitantes dispersos en alrededor de 100 comunidades. Cada grupo era predominantemente autónomo y hablaban diferentes lenguajes. Los colonizadores españoles encontraron cierto parecido entre las casas de adobe de varios pisos habitadas por los indígenas, y los edificios de los pequeños pueblos españoles, por lo que decidieron llamar a los locales Indígenas Pueblo.

Para 1631, el panorama racial y cultural del área había cambiado: el número de comunidades Indigenas independientes se había reducido significativamente a consecuencia de las enfermedades y la violencua de la colonización. Las uniones maritales entre personas de diferemtes razas dieron origen poblaciones que no cabía dentro de ninguna de las categorías raciales anteriores, desafiando jerarquías raciales preestablecidas. La migración hacia Nuevo Méjico de los europeos, criollos, mestizos, mulatos y africanos procedentes de otras partes de Nueva España incluía a los indígenas mexicanos, quienes, como Beatriz de los Ángeles y su hija Juana de la Cruz, trajeron consigo las prácticas y creencias de sus propias comunidades. De hecho, muchos de quienes fueron interrogados por Esteban de Pera durante su investigación, confesaron haber utilizado remedios y pócimas a base de peyote, un cactus alucinógeno cuyo uso era sagrado para los Indígenas mexicanos desde cientos de años atrás.

La idea de que el remedio utilizado por Juana Sánchez en su esposo, haría que su corazón regresara a ella, resuena con un aspecto específico de la cosmovisión prehispánica de los Indígenas Pueblo. El historiador americano Ramón Gutiérrez argumenta que en la época prehispánica los habitantes de la zona del Rio Grande creían que el bienestar de sus comunidades dependía de la salud fisica y psicológica de sus miembros. La fortaleza del ser humano residía entonces en su corazón, por lo que practicantes de magia negra lograban enfermar a las personas insertando objetos dentro de sus cuerpos y drenando sus corazones. Los curanderos lograban sanar esos males, extrayendo los objetos que habían sido insertados en el cuerpo del doliente (When Jesus Came the Corn Mothers Went Away, 1991). Para la época en que Juana Sánchez testificó ante la Inquisición, las creencias prehispánicas sobre los males y sus curas ya habían sido moldeadas de mil maneras, pero su declaración prueba que ciertos temas relacionados con el mundo espiritual de los locales coloreaba la imaginación de quienes colonizaron Nuevo México.

El Nuevo Méjico de la Colonia era mundo lleno de contradicciones. Los cristianos realizaban prácticas antirreligiosas, y a su vez asistían a misa regularmente. Parecían sentir temor de Dios, pero también experimentaban con hierbas y raíces a las que atribuían poderes mágicos. La violencia en contra de las mujeres era común, aunque también lo era la práctica de retaliación. Las mujeres creaban alianzas y se ayudaban entre sí y, sin embargo, denunciaban a sus parientes y vecinas ante las autoridades. Esta era una sociedad compleja en la que los individuos estaban exultantes de emociones y pasiones. Muchas de las mujeres representadas en estos documentos fueron más allá del conformismo servil que se esperaba de ellas, atreviéndose a indagar formas de conocimientos desconocidas para ellas. Al hacerlo, parecieron haber ganado cierta forma de control sobre su situación personal, aunque fuera momentáneamente.

A pesar de que es imposible comprobar la veracidad de los eventos reportados en estas declaraciones, los registros de la Inquisición sugieren que las creencias y prácticas indígenas permearon múltiples aspectos de la vida diaria de la colonia en Nuevo Méjico, abriendo a su vez una posibilidad a las mujeres no Indigenas de tomar represalias en contra de la violencia marital. Y mientras que los colonizadores trastornaron el mundo de los nativos con su llegada, el proceso de transformacion no fue unidireccional. En su intento por controlar a las personas y sus territorios, su mundo fantasioso e intelectual también fue ampliamente transformado.

Winter 2021, Volume XX, Number 2

Juliana (Ossa) Cohen studies the intersection of caregiving practices, religious beliefs and social change. She has been a Teaching Assistant for three different schools at Harvard University, and is a research associate at the Moses Mesoamerican Archive. Juliana was born and raised in Colombia.

Juliana (Ossa) Cohen estudia la relación entre las prácticas de cuidado, las creencias religiosas y el cambio social. Actualmente realiza investigaciones académicas en el Moses Mesoamerican Archive y es Asistente Educativa en tres escuelas diferentes de la Universidad de Harvard. Juliana nació y creció en Colombia.

Related Articles

Indigenous Peoples, Active Agents

Recently, the Amazon and its indigenous residents have become hot issues, metaphorically as well as climatically. News stories around the world have documented raging and relatively…

Beyond the Sociology Books

If you are not from Colombia and hoping to understand the South American nation of 50 million souls, you might tend to focus on “Colombia the terrible”—narcotics and decades of socio-political violence…

Exodus Testimonios

The audience at Iglesia Monte de Sion was ecstatic as believers lined up to share their testimonials. “God delivered us from Egypt and brought us to the Promised Land,” said José as he shared his testimonio with the small Latinx Pentecostal church in central California…