Voices: What Should Be On Everyone’s Agenda

Honoring Humanity: An “Interview” with Richard Mora, Harvard ’99

Interview by Mauricio Barragán Baraja (MBB)

MBB: Why don’t we begin by having you introduce yourself?

RM: Alright. I was born in East Los Angeles, and grew up in Cypress Park, a barrio in Northeast Los Angeles or “NELA.” In 1995, I graduated from Benjamin Franklin High School, and then attended Harvard College. A large part of those four years at Harvard were somewhat of a culture shock. It was the first time I lived outside of L. A., other than visiting family in Mexico. Now I’m studying for my Master’s of Arts in Education at the University of Michigan. Teaching is of great interest to me, which is why I chose Michigan’s program because I will receive my teaching certification in secondary education in the areas of Social Studies and Sociology from the State of Michigan upon completing the program in June.

MBB: Could you comment on your experience at Harvard?

RM: Sure. I left Los Angeles somewhat reluctantly. I was afraid that during the time I was away at Harvard something would happen to my brother. Part of me wanted to stay and take care of him. I worried everyday I was at Harvard, especially when people from back home would call and tell me that someone I knew had been seriously injured or killed. I arranged with my friends to watch out for my brother; to keep him away from gangs. They insisted that I needed to go to Harvard for my family and for community. (pause). I had to learn to pay my respects to the deceased from afar. I took all this with me to Harvard.

MBB: You mentioned your experience at Harvard as being a kind of culture shock. Can you expound on that?

RM: Well, it was a culture shock in two ways. First, there was the issue of race or ethnicity. I came from an area that is predominantly Latin@. My high school was easily over 80% Latin@. So, I had to adapt to the fact that at Harvard the Latin@ presence was less than 10%. Then, there was class. Many of the people I met did not come from a working class background. However, like the issue of race and ethnicity, this also provided me the opportunity to learn from others. This is what I found to be the best part of being at Harvard, interacting with people with lived experiences vastly different from mine. I met people from all over the country, from all over the world. I learned so much from them. For example, my roommates: one was from the Dominican Republic, another from North Carolina, and the third was born in Italy and raised in Massachusetts. Exchanging ideas with others is an invaluable experience. It has helped me relate to others better.

MBB: Would you say that is what you miss the most about Harvard?

RM: Yeah, that and all the libraries and bookstores. (smiling).

MBB: With your background, do you find yourself “connecting” with the people you interview for your research?

RM: Definitely. When I was a senior, I wrote an honors thesis entitled Smile Now, Cry Later. I interviewed mothers residing in NELA who lost one or more children in gang-related homicides. More than once, I cried with a mother, or cried later as I re-lived the moment while transcribing our conversations. Although, it was very emotionally and psychologically taxing, it helped me because it led me to seriously reflect upon my commitment to work with young men and women. Many of the mothers I spoke with impressed upon me the importance of my continuing to work with young people and my continuing to share my ideas with others. I have not forgotten their words, and their desire to save the lives of young people has strengthened my commitment to do the same. While they have not formed an organization, their passion and determination reminds me of Las Madres de la Plaza de Mayo in Argentina

A good example of this is how one of the mothers, who I call Martha, brought the issue of humanity to the center of our dialogue. She rather eloquently stated that she works to help gang members because “if those young men were given birth to by a woman, those young men are human beings.” All children are human beings, yet, many-especially children of color and children who are poor-are demonized by some social scientists and journalists who refer to them with labels such as “super predators.” It saddens me tremendously that people respond to the epidemic of youth violence by supporting repressive measures that are born out of political expediency, especially when there exists research that speaks to the issues our children are contending with and that offers more concrete solutions. For example, the works Lost Boys and Youth in Prison.

MBB: You say that you make yourself “vulnerable,” and that your “spirit is re-nourished” when you speak to high school students. What do you mean exactly?

RM: I mean that I heal spiritually and psychologically whenever I speak to young people about the things that have weighed on my heart and psyche for years. For example, I mention to them that I have known countless people-young and old, gang members and non-gang members-who have been killed in gang-related homicides. I tell them about people I know who have been maimed and crippled, both physically and/or spiritually, by such violence. I describe to them how someone can be pushed to embrace gradual suicide, like using drugs or involving themselves in activities that may expose them to death and/or violence. I reveal to them that I was a very fatalistic teenager as a result of the death and violence that surrounded me.

MBB: So, speaking with young people is sort of like therapy?

RM: Exactly. I don’t think many people understand the impact that such violence can have on the development of children and young people. I remember that growing up I was full of stress-always on edge-and very fatalistic, though you wouldn’t have known it if you interacted with me. But, I felt it inside, and unfortunately I lashed out. It is the one thing that I am most ashamed of but it’s true-growing up I used to fight with my younger brother, my only sibling, quite often. I had very little patience for him. If he got me upset or angry, I reacted with violence. So, here I was inflicting pain on my brother, whose birth is by far the most joyous moment of my life. Where did this violence come from? Our parents never fought. We were fortunate that we didn’t experience abuse in our home. However, there was violence all around us-in the streets-which our parents couldn’t always protect us from.

MBB: How did you address your own stress and violence?

RM: It’s quite interesting because once I came to terms with death and my fear of dying, my fatalism began to fade. I became a much happier person-on the inside. Not surprisingly, it was also about this time that the confrontations between my brother and I began to diminish. I was no longer as haunted by an overwhelming sadness, similar to what I have read that war veterans’ experience. So, I began to read more to understand what I was going through, and by the time I went to Harvard, I was even more prepared to learn.

MBB: You are currently teaching as part of your Master’s work?

RM: Yes. Right now I am student-teaching Social Studies classes full-time at an alternative high school in Ann Arbor by the name of Community High, or as the students like to refer to it, “Commie High.” (smiling).

MBB: (grinning) How’s that going?

RM: Overall, it’s great. You have your good days and your not-so-good days. That’s what excites me about the teaching profession-the fact that no two days; no two classes are going to be alike. You’re always learning.

MBB: Tell me about your pedagogical philosophy.

RM: Well, my pedagogical philosophy is composed of two major beliefs. The first is that lived experience holds a wealth of knowledge. Whether respected or not, lo personal-stories, anecdotes, etc.-is very powerful. It is there that one oftentimes finds la esperanza (hope), el cariño (affection/love), el coraje (rage/anger), y las ganas para seguir adelante; para seguir luchando (and the desire to continue forward, to continue struggling). In order to find this in one’s lived experience, one must engage in the practice of critical reflection.

The second belief is that we all embody much potential, which can manifest as either spiritual beauty or atrocious deeds. That is the individual’s choice. But, as the late Paulo Freire states in Pedagogy of the Oppressed: “while both humanization and dehumanization are real alternatives, only the first is the people’s vocation.”

I want to be there working with students as they seek out their individual and communal dreams and to remind them that they should not forget to care after their elders and protect the world for the unborn generations, while affirming their own self-worth and the humanity of others. I want students to take to heart the words of César Chávez, who said that “we cannot seek achievement for ourselves and forget about progress and prospects for our community”, and that “our ambition must be broad enough to include the aspirations and needs of others for their sakes and for our own.” This is a life-long mission. It is a process that requires time, commitment, unselfishness, and responsibility from everyone.

MBB: So, what you are speaking about appears to be, more than anything, a way of life?

RM: Exactly. We must keep in mind that just because time marches on does not mean we are progressing. I believe you must strive everyday to make yourself more human; to honor yourself by addressing your wounds; and to work outwards by helping other people and preparing the world for the unborn generations. For me this struggle is part of who I am. It is part of my identity. When I refer to myself as a Chicano, in many ways, this is what I mean.

MBB: That’s interesting. For you, Chicano is not reducible to a national identity? You don’t simply equate it to being a Mexican-American or to Mexican heritage?

RM: That’s correct. I am the son of Mexicanos. I consider myself Mexicano de corazón (to the core), but when I say, “Yo soy Chicano,” I am putting forth my politics as well as my cultura and bilingualism. What I mean by this is that I am verbalizing the process of conscientização that I am conscientiously undergoing on a daily basis. Conscientização, as defined by Freire, “refers to learning to perceive social, political, and economic contradictions, and to take action against the oppressive elements of reality.”

MBB: One final question. What do you see as your greatest accomplishment?

RM: Years ago I answered a similar question by stating, the fact that I have managed to stay alive. Now, after much introspection, I would qualify this response and say, the fact that I have not lost my humanity, the fact that I did not become de-sensitized while struggling to stay alive.

Winter 2000

Related Articles

Isabelle DeSisto: Student Perspective

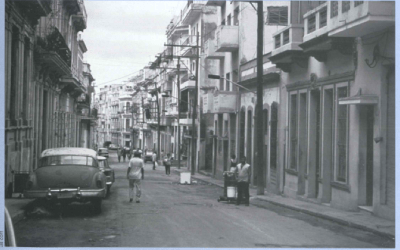

encountered the first obstacle of my trip to the Isla de la Juventud before I even left Havana. Since American credit cards don’t work in Cuba, I couldn’t buy my plane tickets online. But that…

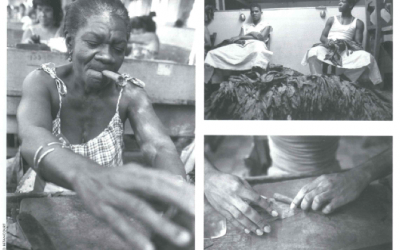

Tobacco and Sugar

“Tobacco and Sugar” is the course that focuses American literatures on the Caribbean, and that acknowledges the unavoidable importance of monocultures for cultural studies. Much of the…

The “Wordly” Classroom

Nearly two years ago, I took 17 graduate public policy students from Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, ages 23 to 40, to Cuba as part of a short course called…