Human Trafficking

An Organized Crime Challenge in Contemporary Latin America

In his foreword to the 2000 United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime, then UN Secretary General Kofi Annan noted the imperative of effective cross-border law enforcement to counter transnational crime: “If the enemies of progress and human rights seek to exploit the openness and opportunities of globalization for their purposes, then we must exploit those very same factors to defend human rights and defeat the forces of crime, corruption and trafficking in human beings.” Annan’s observation highlights one of the central challenges still facing law enforcement agents in an era of globalization, when human mobility is increasingly regarded as central to economic development and the realization of individual opportunity. How can criminal exploitation of vulnerable migrant populations be prevented without excluding them from the potential benefits of international migration?

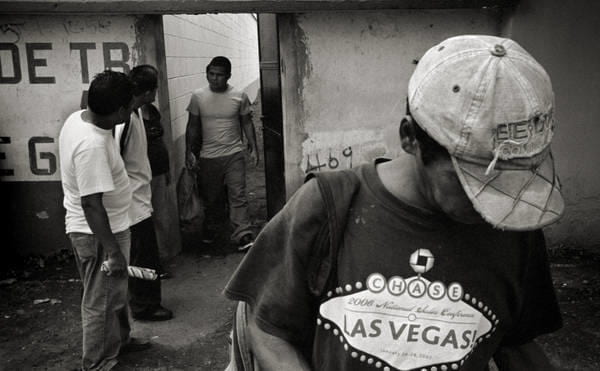

Kofi Annan’s dilemma presents itself with particular force in contemporary Latin America. The continent has a long history of two very sizeable illegal cross-border phenomena: transnational drug smuggling and irregular border crossing. Both activities take place throughout the continent—from Mexico into the United States; from Guatemala, Colombia and Honduras into Mexico; from Paraguay into Argentina. Though the two phenomena are conceptually independent, there is in practice considerable overlap between them. Irregular migrants complain of duress from drug cartels that force them, under threat of death, to carry drugs on their person as they make their perilous journeys across the desert. U.S. border patrol agents report that children (up to 50 percent of trafficking victims in some parts of Latin America, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Global Trafficking in Persons, 2009) are increasingly used as decoys – “part of a ploy to sneak drugs past [U.S.] Border Patrol checkpoints,” as journalist Angela Kocherga points out in her November 6, 2011, report, “Drug Smugglers Using Children as Decoys” (see http://www.wfaa.com/news/national/Border-Patrol-says-smugglers-using-chi…). Small wonder then that border crossing becomes increasingly arduous and that legitimate migrants, those fleeing persecution or seeking work or family reunification, feel compelled to resort to the services of professional agents to enhance their chances of crossing a border.

Human trafficking flourishes in part because of this sort of exploitation. But what is “trafficking?” Thanks to the UN Transnational Organized Crime Convention just cited, longstanding disagreements about the meaning of the term “trafficking” have given way to a broad international consensus. A section of the Convention, the UN Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, sets out a widely adopted definition of the crime of trafficking in human beings. The definition is complex: “Trafficking in persons shall mean the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation.” This definition identifies three crucial ingredients for trafficking: first, some action, which can include movement (whether across an international border or not) but may also consist of simply harboring or recruiting someone for the purposes of exploiting them; second, except in the case of children (children are therefore to be considered “trafficked” under this definition, even if they agree to it), some means, such as coercion or deceit to recruit the trafficked person; and third, exploitation as the purpose of the action and the coercion. In short, someone is a victim of trafficking if they are recruited by force or deceit in order to be exploited. The term “exploitation” is intentionally not defined in the Convention since the signatory states could not reach agreement on its scope. For example, there was (and remains) no international consensus on whether prostitution ipso facto is exploitation. Cultural, social, legal and economic variations affect whether conduct is considered exploitation in a particular context.

In Latin America, there is broad consensus on the existence of all three elements within the crime of trafficking in persons in a wide range of contexts. Though the profits from trafficking are lower in Latin America than on any other continent apart from Africa, the numbers affected are just as significant, as Louise Shelley points out in Human Trafficking: A Global Perspective (Cambridge University Press, 2010). According to the International Labour Organization, there are approximately 250,000 trafficked persons in Latin America. Other international estimates place the number as high as 700,000, though all agree that reliable data do not exist. Trafficking affects all sections of the population, though the type varies. Child trafficking is endemic and very widespread across the continent. Three types of child trafficking are well documented: for sexual and labor exploitation; for engagement in armed conflict; and for transnational adoption. Thus Central American and Caribbean countries have become renowned sex tourism destinations, with children trafficked from rural areas to border towns, urban centers and tourist destinations to supply the demand (see Alex A. Aronowitz, Human Trafficking, Human Misery: The Global Trade in Human Beings, Westport: Praeger, 2009). According to a 2006 Inter-American Development Bank report, half a million children work as prostitutes in Brazil, while Colombia is a major exporter of girls for sexual exploitation in the United States, Europe and the Middle East. Children are also trafficked for agricultural labor and domestic servitude; in some cases drug cartels are reported to have forcibly recruited young children as beggars. Moreover, for decades Latin American children have been trafficked for use in armed conflict. Colombia’s long internal conflict has been a particularly egregious recruiting ground for young boys and girls, for direct engagement as soldiers on the battlefield but also as auxiliaries servicing the sexual, portering or cooking needs of adult combatants, according to the UN Security Council’s 2009 report on children and armed conflict in Colombia. Finally, there are longstanding allegations of baby trafficking to service the international demand for adoptees. This is a controversial topic. Some child rights advocates question claims of baby selling and defend poor mothers’ rights to give babies they cannot care for up for adoption to loving families. But many others express concern over trafficking connected to the lucrative market in babies that has fostered a flourishing adoption business. During the 1990s and early 2000s, Guatemala, one of the poorest countries on the continent with a large, disenfranchised indigenous population and history of brutal civil war, was a key recruiting ground for adoptive babies. The financial opportunities afforded by this business pushed Guatemala to become one of the top three suppliers of international adoptees and generated massive foreign exchange for the country. Yet persistent allegations of coercion, baby selling and profiteering eventually led to the suspension of international adoption from Guatemala in 2008.

Latin American women and men are also extensively trafficked for sex and labor, both within the continent and further afield. Brazil and Colombia stand out as countries in South America where trafficking is especially pervasive. In Brazil, most notably in the impoverished north and northeast regions, men are trafficked for forced labor particularly in the agricultural sector; women for exploitation in the gold mines, in the sex industry and in domestic labor. Other aspects of trafficking in Latin America are of more recent origin, a response to changing global markets and law enforcement patterns. They include trafficking in persons for organ harvesting at the U.S.-Mexico border, a secretive but increasingly lucrative business, and the exploitation of human “mules” or carriers to ferry illicit drugs across international borders.

Efforts to end or curb human trafficking, linked to the slave trade and to the sexual exploitation of women, date back to the early twentieth century and continue to preoccupy legislators and public figures across the political spectrum. Most anti-trafficking efforts focus on criminalization of traffickers and cross-border law enforcement collaboration to identify transnational trafficking networks. Some recent initiatives, however, have also included more victim-focused measures, including the provision of counseling and “rehabilitation” services, and increased access to health care for trafficking survivors. Unfortunately it is not clear that these measures are reducing the impact of contemporary trafficking in Latin America. A UN study found that the cumulative product of investigation and prosecution of trafficking cases between 2003 and 2007 in Latin America was “a few dozen convictions.” A Massachusetts General Hospital investigation in Brazil revealed that there were “no specific health-care facilities for sex trafficked women and girls” in Rio de Janeiro or Salvador, despite the reputation of both cities as hubs of sex trafficking and sex tourism. Law enforcement and rehabilitative interventions do not appear to be making a significant contribution to curbing the impact of human trafficking in contemporary Latin America.

A more holistic engagement with the trafficking phenomenon would likely yield better results. It is instructive to think of trafficking as the product of two different supply and demand equations. One of the equations, external, is closely related to migration pressures. The demand side comes from would-be migrants who cannot legally access opportunity abroad. The supply side consists of illicit professional border-crossing services to facilitate that access: con men and women who persuade, recruit, harbor and transport people with false promises of jobs or opportunities. As legitimate, safe border-crossing becomes harder, especially for unskilled and uneducated populations, these services become more attractive, even essential. A report submitted to the U.S. Congress highlighted the extent to which border-crossing points had become “the newest trafficking focal points.” This is as true for the Guatemala-Mexico border as it is for the Mexico-U.S. frontier: “women who are unable to enter the United States end up being forced into prostitution in Mexico.”

Most discussions of trafficking focus on another, internal supply-demand equation: the supply of populations exploitable with virtual impunity and the demand for cheap sex, labor, or other products of human exploitation. This equation balances on the huge profits to be made, the low risks attached to this profiteering and the enormous, ready market for the services of exploited populations. Demand is fueled by human traffickers and their clients: pimps and brothel owners, factory and farm employers, private households in search of domestic workers, child pornographers and sex tourists. Traffickers have a ready source of clients for the human services they peddle and the opportunity to become extraordinarily wealthy without the risks that drug or arms smugglers face.

In Latin America, as elsewhere around the globe where trafficking flourishes, both types of supply and demand chain exist. Trafficking occurs from the poorer to the richer areas, within the country, the region and across the world. It depends on an absence of survival options for marginalized and impoverished communities, on the aspirations linked to migration and on the profits to be made from exploiting these aspirations. Until more anti-trafficking resources are spent on generating education, training and employment opportunities for the communities vulnerable to trafficking, either within their own countries or through lawful migration options, traffickers will continue to find demand for their services, and criminal deterrents will simply increase the danger of trafficking routes and extortionate demands affecting the victims.

Spring 2012, Volume XI, Number 3

Jacqueline Bhabha is the Jeremiah Smith Jr. Lecturer at Harvard Law School, Research Director at Harvard’s FXB Center for Health and Human Rights, Adjunct Lecturer on Public Policy at Harvard Kennedy School, and Harvard’s University Adviser on Human Rights Education.

Related Articles

Transmigration in Mexico

English + Español

En abril del 2010 una delegación oficial de El Salvador encabezada por Francis Hato Hasbún, el Secretario de Asuntos Estratégicos del gobierno del Presidente Mauricio Funes, visitó México…

Organized Crime as Human Rights Issue

English + Español

It was a horrifying scene— 72 people murdered all at once. One survivor bore witness to the massacre. The dead were migrants, mostly Central Americans; 58 men and 14 women trying to…

First Take: Organized Crime in Latin America

English + Español

Dealing with transnational organized crime is now an official part of U.S. security strategy.

A strategy document, issued by the White House in July 2011, speaks of organized crime groups…