In Search of a Hummingbird

Preservation, Restoration, and Human Development

Like the interior of a sealed adobe oven, the early morning air smothers us as we search in vain for the elusive Honduran Emerald hummingbird. Organ pipe cacti, acacia trees, and thorn scrub sit in chaotic patches, covered with epiphytes, dead branches, and bird nests—the entire mess sporadically adorned with red flowers. Our guides suddenly hunch, pointing to a nearby flower, cupping their ears to amplify the tickling buzz.

The Honduran Emerald (Amazilia luciae) holds promise for the local population to benefit from low-impact ecotourism, but the hummingbird’s future is tenuous at best. Endemic to Honduras, its habitat is restricted to the Aguán River Valley, in an arid rain shadow on the southern side of Pico Bonito National Park. Its de facto island home shrinks every day—less than eight square miles at two separate sites—putting it near the top of the World Conservation Union’s (IUCN) Red List as a critically endangered species. The next step is extinction.

I didn’t expect a DRCLAS internship grant to put me on the trail of an elusive hummingbird. I wasn’t alone in the search though. Alex, my Colombian brother-in-law, accompanies me to capture footage for a documentary film. Our mission is to compare the various organizations and landscapes we’re visiting within the region—from Guatemala to Honduras to Belize. José Luis, an extension worker from FUPNAPIB, the Pico Bonito National Park Foundation, also accompanies us. Above all, we have some expert help in the form of local guides, former workers for the Standard Fruit Company.

As an intern for the Cambridge-based EcoLogic Development Fund, I’d already learned that nongovernmental entities are all that stand between conservation and destruction of biodiversity hotspots throughout Honduras because of government inaction and lack of funding. FUPNAPIB, one of many Central American conservation organizations funded by EcoLogic, strives to breach the gap. Sustainability and impact are exactly what I’ve been thinking about all summer—trying to craft a simple and generally applicable system of indicators to measure impact across EcoLogic’s beneficiary organizations in the broad areas of conservation, human livelihoods and institutional sustainability.

My mind is wandering toward the theoretical as we follow our guides. Suddenly, we spot the hummingbird. It is flying at highspeed, constantly reversing direction, zooming in and out of view as it bounces chaotically between flowers. Its chest and throat are a dull blue-green, but when it flashes its shiny green back feathers it is easy to see why the common name in Spanish is “Diamond Collar.” But capturing its brilliance with our eyes is the easy part. The next challenge we face is trapping its image on film.

I stare at the tiny bird. I try to conceptualize the linkages between this one hummingbird, one little feature of a complex mosaic of human-landscape interactions in and around a single national park, in one small corner of Central America.

This corner of the world’s nearest town is a dusty outpost named Olanchito. Unlike the humid and hopping town of Ceiba that sits between the park’s northern entrances and the Caribbean, Olanchito is relatively unknown to foreign tourists, as is its dry forest habitat.

FUPNAPIB has trained guides to lead the occasional tourist to this secluded spot, post signs and help construct park trails. Our two guides, Roque and Freddy, have chosen this work over the nearby banana and pineapple plantations despite not receiving paychecks for almost nine months. On the previous night’s drive from Ceiba to Olanchito, Gerardo, the high-energy, supremely dedicated FUPNAPIB director, observed how grateful he is for EcoLogic’s sensitivity to the fact that his foundation is absolutely dependent on outside funding, usually granted in short spurts for targeted projects rather than administrative overhead.

Meanwhile, his workers live from hand to mouth, eking out a daily existence. The government may soon pave Olanchito’s potholeladen dirt road, enabling better transport of produce and labor, but multiplying the direct pressures on the Emerald hummingbird’s tiny habitat. It is a constant balancing act between nature and development.

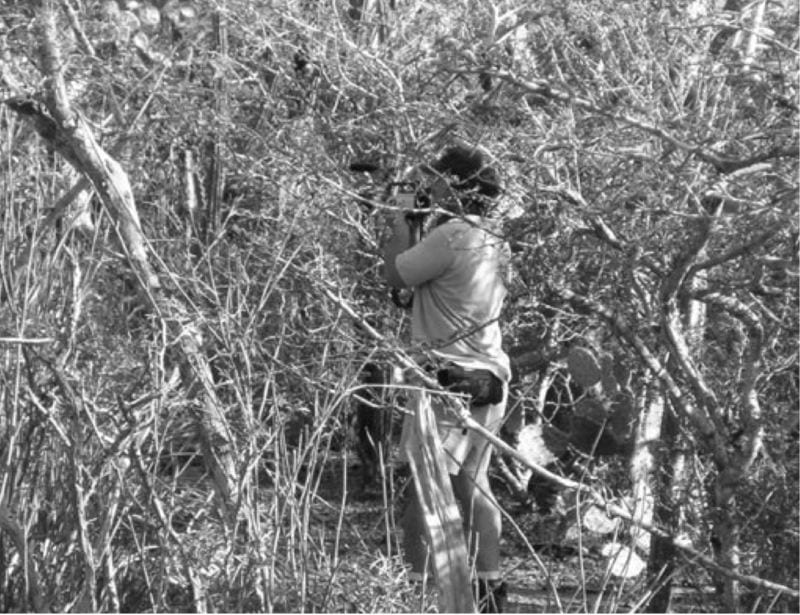

Besides complaining about this short-term funding dependence, Gerardo is also furious at environmentalists who, in his view, don’t always get the connection between livelihoods and conservation. He derides “preservationists” for idealizing nature and forgetting about human and economic development needs. But FUPNAPIB’s most obvious mission—managing a national park—intersects preservation, restoration, and human development. Now, however, all attention is focused on the tiny bird, rather than environmental philosophy. Roque and Freddy dive into the thorny scrub, and Alex scoots in after them, determined to film the bird that has brought us all here. The thorns scratch and tear at their skin, but they find a place to wait patiently for the Emerald. In the end, Alex does capture the bird on film, if only for a fleeting moment.

Fall 2004/Winter 2005, Volume III, Number 1

David Kramer is a master’s candidate in public policy at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, taught in Cali, Colombia for four years. He hopes to work in the region again, focusing on sustainable community development and biodiversity conservation. He dedicates this article to the memory of FUPBNAPID director Gerardo Rodríguez, who was killed in a tragic car accident in Honduras, just as this issue of ReVista was going to press.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter: Flora and Fauna

Ellen Schneider’s description of Sandinista leader Daniel Ortega in her provocative article on Nicaraguan democracy sent me scurrying to my oversized scrapbooks of newspaper articles. I wanted to show her that rather than being perceived as a caudillo

Bilingual Aesthetics: A New Sentimental Education

After an exhausting game of soccer with a crew of Mexico City street children, Vicente, a young teenager of 13 said, “Vamonos a la verga.” It was my third day with Casa Alianza, the international…

Nature and Citizenship

Two first-time visitors to the Galapagos archipelago begin their experience in exactly the same way. Two hours after departing mainland Ecuador, their plane descends towards the island of…