In Search of Mexico’s National Cuisine

¡Que vivan los tamales (y tortillas)!

Growing up in the Midwest in the 1970s, I ate a bland diet of meat and potatoes and soothing Jell-O salads. Mexican food remained unknown territory until my brother moved to Las Cruces, New Mexico, and married a Mexican-American woman. At the wedding rehearsal dinner, his future mother-in-law prepared gorditas, fat corn tortillas reminiscent of pita bread. Never having encountered such a thing before, I observed another of the groomsmen add a heaping spoonful of salsa and begin to devour the gordita with obvious relish. He was an Anglo, so I assumed it must be safe and followed his example, not realizing that as a Texan, he was accustomed to eating the devil’s own spice. I took a bite and suddenly felt steam come boiling out my ears. My subsequent dance around the house, culminating with my head stuck futilely under the kitchen faucet, has become a family legend. This initiation into Mexican food proved to be one of the turning points of my life; indeed, my professional career may be an attempt to cope with the trauma.

After finishing a bachelor’s degree at the University of Illinois, I followed my brother to the Southwest. I began work on an M.A. in history at New Mexico State University while learning to cook Mexican food from my sister-in-law’s mother. She never learned to speak English and my Spanish was quite rudimentary at the time, so the lessons were conducted the old fashioned way, by touch, smell, and taste. I mixed the dough for tamales by hand to learn the proper texture, and to describe the type of pork to use for the filling, she gave me a slap on the flank.

Following this apprenticeship in Mexican history and cooking, I went to Texas Christian University for my Ph.D. But even while studying under William Beezley, the dean of Mexican cultural history, the idea of combining the two interests to write a dissertation on Mexican cuisine seemed unimaginable at first. Nevertheless, as I prepared for the comprehensive exams, I also read the works of Mary Douglas, Claude Levi-Strauss, Jack Goody, Sidney Mintz, and Arjun Appadurai. Encouraged by their examples, I made research trips to the Benson Library of the University of Texas. What I found in nineteenth-century Mexican cookbooks bore little resemblance to the tamales and gorditas I had so recently learned to prepare. Those volumes ignored popular street foods, based on the pre-Hispanic grain, maize, and instead gave recipes for elite Spanish and French dishes. I had stumbled on the culinary expression of Mexico’s national identity crisis: a mestizo or mixed-race people who inherited the European disdain for their Native American ancestors.

My dissertation research in Mexico proved even more surprising. After my shocking initial encounter with chiles, I was amazed to discover that Mexicans do not even eat chiles for the heat, unlike some Texans who indulge in masochistic jalapeí±o popping contests. Instead, they blend the tastes of different chiles to form complex sauces called moles. Regular chile eaters (myself now included) develop a tolerance to the capsaic acids in the chiles, and so they need to eat hotter peppers to get the same effect, which is why Mexican foods taste so fiery to newcomers. Even familiar foods seemed strange in Mexico; gelatin was ubiquitous in chile-flavored aspics and tropical fruit desserts, but little marshmallows were nowhere to be found.

Another surprise came from the regional diversity of Mexican cuisine, a legacy of both the pre-Hispanic civilizations and the Spanish colonization. The indigenous foods of the Maya in the Yucatan and of the Zapoteca and the Mixteca of nearby Oaxaca, for example, are quite distinct notwithstanding similarities such as the use of banana leaves to wrap tamales instead of the corn husks more frequent farther north. The Yucatecan use of habanero chiles and achiote paste produces a completely different taste from the chile pasilla and hoja santa used to prepare Oaxacan moles. The central highlands around Mexico City are the center of the greatest culinary mestizaje, a process exemplified by mole poblano, a turkey cooked in a deep brown sauce that contains a complex mixture of Old World spices and nuts with New World chiles and chocolate. The quintessential dish of the Pacific Coast region, including Guadalajara, is likewise a mestizo stew, pozole, of hominy and pork. On the Gulf Coast, by contrast, seafood is often cooked in a Mediterranean style, for example, snapper Veracruz. The foods seen most often in the United States tend to come from the north, a region of Spanish settlement where wheat and beef were the preferred foods. This tremendous variation of region, class, and ethnicity impeded the development of a common national cuisine and of Mexican nationalism in general.

Cookbooks also offered a window on the elusive realm of domesticity in nineteenth-century Mexico. Interpreting them proved problematic, however, for most were written by male intellectuals as instructional literature for women. The few available manuscripts of family cookbooks allowed some insights on the intersection between oral and written culture. Indeed, domestic writing was one of the first socially acceptable forms of literary production for women at the time. Comparing the manuscripts with published volumes, I could see the process by which women read the latter works, adapting them to the kitchen by selecting practical recipes, deleting extraneous ingredients, and fixing occasional problems. These home cooks certainly ignored such absurd concoctions as frijoles rellenos, in which each bean was individually stuffed with cheese, dipped in egg batter, and fried. I could only gain a glimpse into this domestic world because of the limited number of volumes available when I did my fieldwork, but in less than decade, a cottage industry has grown up publishing manuscript family cookbooks, so the next researcher will achieve far more than my stumbling efforts.

I also studied the history of Mexican nutritional science, which emerged as an important part of the national discourse at the turn of the last century. When large-scale industrialization began during the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz (1875-1911), the vast majority of the rural population contributed little to the market economy. The ruling científicos (scientific party) sought to explain this low productivity, but the racial theories of Anglo-American Social Darwinism had little appeal because both the elite and the masses were predominantly mestizo. Instead, they resorted to the newly developed science of nutrition and claimed that the Native American staple, maize, was inferior to the European grain, wheat, and that progress would be impossible until the masses were weaned from the former and taught to eat the latter.

Nutritionally, this argument was spurious, as the Mexican National Institute of Nutrition demonstrated in the 1930s with the assistance of grants and researchers from the Rockefeller Foundation. Nevertheless, the científico elite correctly perceived that the hardy Native American grain was the foundation of the subsistence rural economy, and that the adoption of the fragile and expensive European grain would draw the villages into the market economy. The Porfirian goal was finally achieved not by replacing maize but rather by making it a commodity through mechanical corn mills, automatic tortilla machines, and dehydrated tortilla flour. In retrospect, the goal of this “tortilla discourse” was to divert attention from agrarian reform, which would have provided Mexican campesinos with the land to raise the foods, especially beans, needed to obtain a balanced diet.

Once the threat of revolutionary reform had abated, about 1940, the urban middle class finally embraced the lower-class maize dishes as the basis for a national cuisine. The spread of processed foods to the countryside sent folklorists rushing to preserve the previously scorned vernacular cuisine. The most prolific of these culinary researchers, Josefina Velázquez de León, published more than a hundred and fifty cookbooks, including a volume of regional recipes that became the model for future cookbooks seeking to represent the Mexican national cuisine. Mexico City restaurants also became a site for the cosmopolitan elite to experiment with diverse provincial dishes, especially since modern transportation made local ingredients available while massive rural-urban migration brought cooks from all over the country.

Nevertheless, the incorporation of indigenous foods came only hesitantly, as can be seen in the case of cuitlacoche. This maize fungus (Ustilago maydis), the blight of Midwestern farmers in the United States, was a popular delicacy among the formerly corn-worshipping Nahuas, who referred to the black spores as “excrement of the gods” and ate them in rustic corn fritters called quesadillas. Cuitlacoche became acceptable on elite tables only in the 1940s, when gourmet Jaime Saldívar devised a suitably refined preparation, in críªpes with béchamel sauce, thereby using French haute cuisine to ritually cleanse the native dish. By the 1990s, the fungus had become known as the “Mexican truffle” and it formed the mainstay of the so-called “nueva cocina mexicana” as chefs began preparing it in ravioli, soups, and endless mousses. For an elite that had dined for so long on continental cuisine, indigenous dishes ironically became the only claim to a distinctive national cuisine.

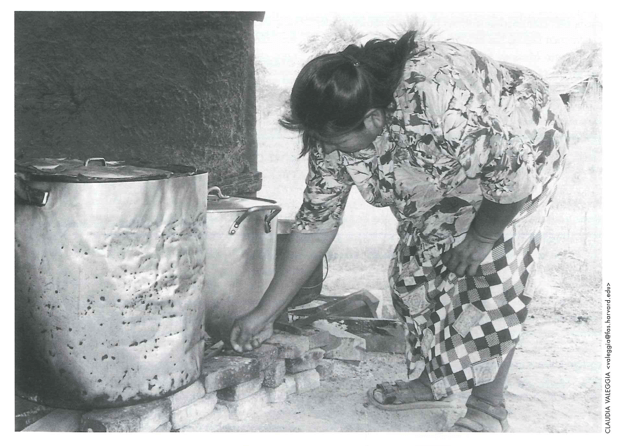

A Namqom woman prepares a fire: “the elusive real of domesticity”

Ultimately, my volume on maize and wheat and Mexican national identity is merely an interpretative synthesis, and perhaps a premature one at that, for a tremendous amount of research remains to be done. Fortunately, the stigma that food history is not a serious subject is being rejected by a growing number of excellent scholars, most notably Virginia García Acosta, Martin González de le Vara, José Luis Juárez, Janet Long, Rosalva Loreto López, and John Super. Moreover, sources have become ever more available through the appearance of family cookbooks as well as the magnificent series of ethnic cookbooks being published by Conaculta.

Research topics abound for aspiring graduate students with an interest in Mexican cuisine. When I wrote my second book, a biography of the Mexican film comedian Cantinflas, I was struck by the significance of popular foods such as tequila and chicharrones (pork cracklings) in his humorous discourse. Currently I am studying the modernization of the Mexico City meat supply during the nineteenth century, and other food industries, particularly beer, call out to economic historians. Ethnohistorians with indigenous language skills are sure to refine our understanding of the role of food in the ongoing encounter between Spaniards and Native Americans. Intriguing works of gender studies could be written about the significance of women and gays in the Mexican restaurant business. But for anyone setting off in search of culinary history in Mexico’s archives and libraries, just remember to bring a snack to keep you going until lunchtime.

Spring/Summer 2001

Jeffrey M. Pilcher is associate professor of history at The Citadel in Charleston, South Carolina, and he has lectured at the Culinary Institute of America in St. Helena, California. His first book, ¡Que vivan los tamales! Food and the Making of Mexican Identity (1998), won the Thomas F. McGann Memorial Prize. He is also the author of Cantinflas and the Chaos of Mexican Modernity (2001).

Related Articles

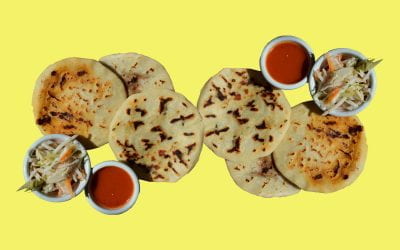

Salvadoran Pupusas

There are different brands of tortilla flour to make the dough. MASECA, which can be found in most large supermarkets in the international section, is one of them but there are others. Follow…

Salpicón Nicaragüense

Nicaraguan salpicón is one of the defining dishes of present-day Nicaraguan cuisine and yet it is unlike anything else that goes by the name of salpicón. Rather, it is an entire menu revolving…

The Lonely Griller

As “a visitor whose days were numbered” in Buenos Aires, Argentina, he tossed aside dietary restrictions to experience the enormous variety of meat dishes, cuts of meat he hadn’t seen…