International Theater Festival

Culture in Action

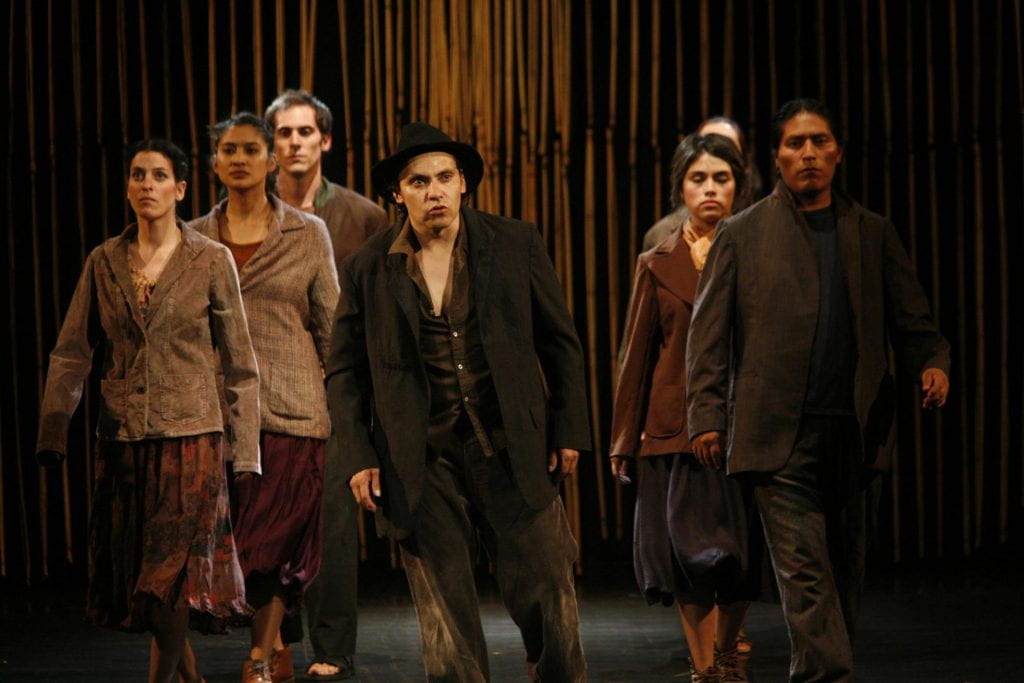

La Odisea Teatro de los Andes performs in the International Theater Festival. Photo courtesy of Maritza Wilde

The challenge began at a café in Madrid on a cold morning, when two Spanish colleagues dared me to organize an international theater festival in Bolivia. We were talking about Latin American theater and how little promotion theater was receiving in some Latin American countries. My colleague and friend Luis Molina, director of the CELCIT (Latin American Center of Theater Creation and Research), observed, “You are the perfect person to organize an international theater festival in Bolivia; you have the contacts and the experience.” I evaded his comment with something along the lines of “It’s complicated.”

Back in Bolivia a few days later, I started to think about the idea. I figured the most adequate place to hold the event was the city of Santa Cruz de la Sierra, capital of the department of Santa Cruz, which shares a border with Brazil. Although it is Bolivia’s most important city, I discarded La Paz from the beginning because of its altitude: some 12,000 feet above sea level. Santa Cruz with its increasingly prosperous society was experiencing a demand for cultural growth. The reality exceeded my expectations. Four months after my arrival from Madrid, I presented the project to three institutions in Santa Cruz de la Sierra.

It was 11:30 a.m. on another morning, a hot and humid one, and I was leaving the offices of a cultural institution in Santa Cruz. It had been my third appointment of the day, and the third institution to offer financial support for my project. It was not yet noon, and I already had the financial resources and institutional support to go ahead with the first international theater festival in Bolivia. This was nothing short of amazing. From my previous experience as an independent theater director and actress, the knowledge that theater can find its rightful place in the culture of our peoples filled me with a deep satisfaction.

Six months after the challenge in Madrid, the first International Theater Festival of Santa Cruz de la Sierra, the first of its kind in Bolivia, was inaugurated. The public’s response was incredible; performance after performance, the people seemed amazed at the event and very emotionally receptive. It was a heterogeneous public, made up of young people filled with an expectant curiosity and older people who seemed to be emotionally moved, especially by the international performances they saw. Every one of the international performances received standing ovations. The tickets were sold out for every single performance.

The success of this first experience in 1997 encouraged me to undertake a second project, this time in La Paz. At this point, I figured if people could play soccer here, they should very well be able to perform theater. Most importantly, La Paz was the city I lived in, so it would be easier to give continuity to the project. So, taking advantage of the fact that La Paz had been named “Capital Iberoamericana de la Cultura,” we held the first International Theater Festival of La Paz, or FITAZ, in 1999.

This second experience was very different from the first, and the altitude proved to be the least of our troubles. Although we had the support of important municipal institutions, we faced multiple financial problems that threatened the success of the event. Yet the good quality of the plays drew highly positive reactions from the public and the media. Headlines like “The FITAZ dazzles La Paz” were common during those ten days. Some people approached me on the street to congratulate me and express their gratitude with words like “Thank you for this festival that filled us with joy and optimism”.

Although the festival had been programmed to be held every two years, the Mexican ambassador to Bolivia advised me to hold another the following year. She said, “Maritza, don’t let the audience cool off; don’t let them wait two years.” After the financial difficulties we faced, I was ready to give up on the project altogether. But I thought of the enthusiastic congratulations on the street and the supportive advice of the ambassador, I and decided to forge on for the year 2000—the beginning of the new century.

The festival has now been held seven times. For my colleagues, especially the young ones who are starting out in playwriting, directing and acting, this festival has become a very important platform for their own inspirations and creation and an international arena in which to present them. It is very gratifying to see that I was not wrong to take the advice of the Mexican ambassador at the time. Just as there have been difficulties, there are many names and faces which, as a woman of theater, inspire me and elevate me to what I believe is one of the highest qualities of the human spirit: gratitude.

Fifteen years after that morning in Madrid, we see 2012 as a year full of new accomplishments for the theater community of Bolivia; the FITAZ will be held for the eighth time in March 2012. I want to finish with the thought that has guided me throughout my work as an actress and director, which is the belief that theater is peace, even in war, and freedom even in slavery.

Maritza Wilde is an actress and theater director who has studied in Spain and France. Currently she is the director of the International Theater Festival of La Paz and of the FITAZ “Theater for Peace in the World” Foundation.

Related Articles

A Review of Alberto Edwards: Profeta de la dictadura en Chile by Rafael Sagredo Baeza

Chile is often cited as a country of strong democratic traditions and institutions. They can be broken, however, as shown by the notorious civil-military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet (1973-1990). And yet, even a cursory view of the nation’s history shows persistent authoritarian tendencies.

A Review of Born in Blood and Fire

The fourth edition of Born in Blood and Fire is a concise yet comprehensive account of the intriguing history of Latin America and will be followed this year by a fifth edition.

A Review of El populismo en América Latina. La pieza que falta para comprender un fenómeno global

In 1946, during a campaign event in Argentina, then-candidate for president Juan Domingo Perón formulated a slogan, “Braden or Perón,” with which he could effectively discredit his opponents and position himself as a defender of national dignity against a foreign power.